Whether you know me well or whether you only know me from the altar, you have likely made some assumptions over the past 15 months about who I am and what I like. Your observations from just how I say Mass may have led you to conclude that I am someone prefers organ and traditional hymnody over guitars and praise music and that I think some parts of the Mass, at least some of the time, should be said in Latin. If those have been your suspicions, they are all correct.

What may come as a surprise, however, is that I haven’t always been the way I am. My convictions and preferences have both changed significantly throughout my life. From 8th through 12th Grade, I played piano in the contemporary group at the 10:30 Mass every Sunday. For most of that time, I was even the director of that group and deeply enjoyed the music we made. Despite my efforts to move our repertoire from the 1980s to something actually ‘contemporary’, most of the songs we played was written by people like Joncas and Hass, Schutte and Foley. Due to its popularity, the song I probably played the most was “All Are Welcome” by Marty Haugen; and to confirm how deeply this ditty is lodged in my brain, I sat down at the piano while writing this homily to see if I could still play it by memory; and yes indeed, I still can.

I have a soft spot for a good number of songs from that era, but I can muster nothing nice to say about that one. Musically, it’s obnoxious; poetically, it’s lame; theologically, it’s muddy. If I never had to sing it again in my life, God could only be so good to me. Thinking about today’s Gospel, however – a Gospel that seems to be a perfect occasion to sing “All Are Welcome” – I can only double down. What this Gospel has led me to realize is that the idea of ‘welcome’ is contrary to the very Gospel itself.

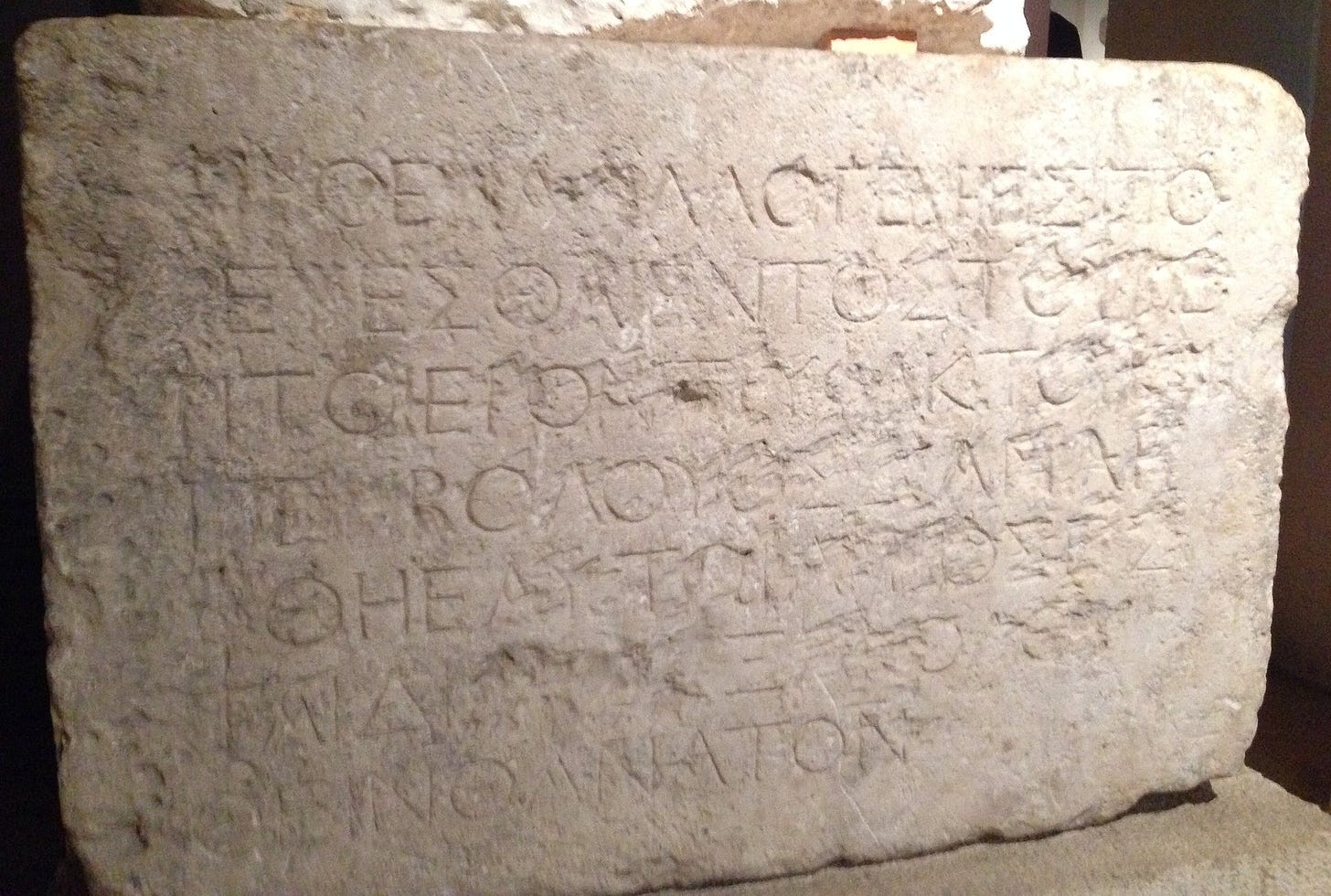

In the Gospel, we heard the story of Jesus healing ten lepers, one of whom turns out to be a Samaritan. The word Jesus uses that here is translated as “foreigner” is an odd one. It is odd because it is not found anywhere else in the New Testament. The New Testament lacks the language to speak about foreigners and strangers. Yet the surrounding Jewish world did not. That same word in Greek was written broadly and publicly in the outer court of the Temple – the court designated to the Gentiles – forbidding further entry upon the penalty of death to any “foreigners”. Christ’s use of the word is unmistakably intentional and ironic. The other nine, as Jews, are readmitted to the full breadth of Jewish political, social, and religious life. But this Samaritan, whether or not he is a leper, will always remain a foreigner and will forever be restricted from the same.

By identifying him as a foreigner, Christ unveils the irony: the nine Jews are now able to enter the Temple to worship God and are never seen again; but it is the foreigner, who could not ever enter the Temple, who alone returns to Christ the true Temple and falls in adoration and thanksgiving at his feet. And what this foreigner has done – his act of faith in Christ – is what all are meant to do, regardless of race or ethnicity. We are not supposed to see this foreigner as a foreigner – as someone other than us – but rather as standing in for us, representing who we all should be.

If the New Testament cannot speak of “foreigners”, and its only use of the word is meant to underline our common human destiny in Christ, then I do not believe we as Christians can rightfully use the word “welcome”. “Welcome” always implies a “foreigner”, and the Gospel does not allow us to see foreigners. We welcome people into our homes who have no other right to be there. We welcome strangers in from the outside as people on the inside who’s welcome it is to give. The more we welcome people the more we remind them that they are still people needing welcome. That they are still strangers and foreigners. That they do not yet belong. The Church cannot “be welcoming” because the Church cannot think in the categories of foreigner and native, stranger and friend. The Church can only think and speak of others as brothers and sisters. And we do not welcome brothers and sisters, even if they are estranged, into where they rightfully belong and into what is already theirs.

If you asked me to summarize the essence of the Gospel in a single verse, there’d be a few in competition for top billing, but on the list would certainly be Ephesians 2:13: But now in Christ Jesus you who once were far off have become near by the blood of Christ. Christ has made strangers into family, aliens into citizens, foreigners into natives, slaves into friends. In him, all distinctions fade away. As we sing in one of my favorite hymns: All are one in thee, for all are thine. A few weeks ago, one of the 6th graders in the school puzzled her way to the very heart of Christianity. As I taught them that to love means to will the good of the other, she raised her hand and objected: Wait a minute. If Jesus tells us to love our enemies. And loving them means we want what’s best for them. Then we can’t really have any enemies. That’s exactly it. Christ calls us to unity and whatever implies that unity in Christ is not absolute has no place in Christianity.

To my mind, the language of welcome undermines the universality of the human family and the universal mission of the Church and therefore needs to be removed. As humans, we know every member of the human family is equally human and belongs equally to that family. As Christians, we believe that everyone is individually, personally, and uniquely created and loved by God. We believe that Christ became human to redeem the whole of humanity and built the Church as the ark to carry the whole human family from this broken and divided world unto the perfect harmony of heaven. We believe that in heaven all of creation will be restored and, please God, all our voices will sing in unison with all the angels and saints in one chorus of praise in the world without end.

Now, I’m aware that we all use the word “welcome” with the best of intentions. We welcome people and want people to feel welcome in the Church because we want them to become one with us in this life and in the next. And with the limits of language being what they are, there may be no way to get around using the word “welcome” for lack of anything better. But my point is that we need to be aware of what the word implies and think first and foremost of our common humanity and common destiny when we “welcome” anyone back to the Church or receive them here for the first time. We should not look at them as a foreigner who has come to us from far off but as a brother or sister who has come home. One does not – and should not – need to be welcomed into their own home.

Homily preached October 9, 2022 at the Cathedral of Mary Our Queen.

Positive outlook on daily thoughts, which consumes me a lot, like why can't we all get along, be courteous, patient, and remember each of us has story.