The word “liturgy” is sometimes used as a synonym for “Mass”; and while the Mass is, indeed, a liturgy, not every liturgy is a Mass. The celebration of the sacraments, whether they take place within the context of a Mass or not, are all liturgies; so too are the ‘sacramentals’ like the blessing of a pet or an exorcism, which, depending on the nature of the beast, might be one and the same. “Liturgy” is a broad umbrella, under which falls all of the official, public worship of sacrifice, thanksgiving, supplication, and praise that the Church offers through Christ in the unity of the Holy Spirit to the glory of God the Father.

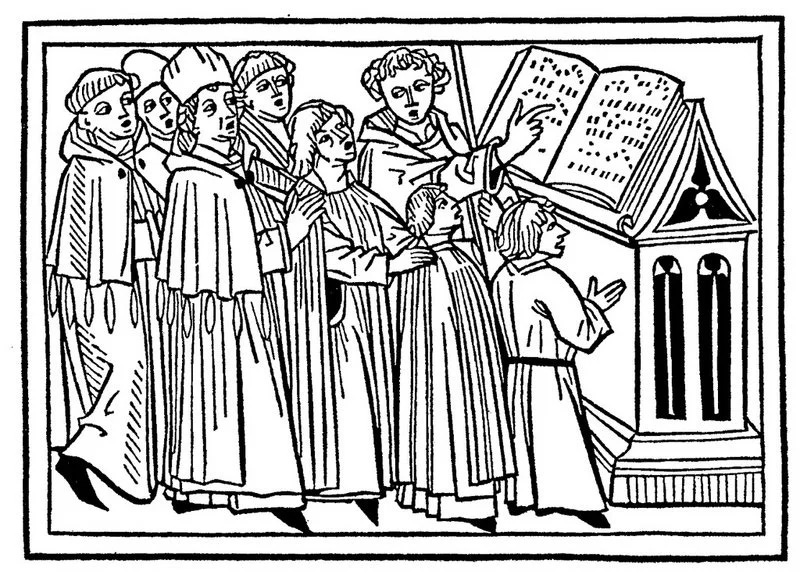

Among the Church’s most ancient and precious liturgies is the Divine Office, which is prayed in various “hours” throughout the day. Visiting a monastery, one would see the monks gathering in the abbey church between 3 and 4 A.M. for Matins. Then, they would return at dawn for Lauds and again after breakfast for the tiny office of Prime before beginning the day’s work. The hours of 9 A.M., Noon, and 3 P.M. are for the shorter offices of Terce, Sext, and None. Vespers is prayed at 6 P.M. and then Compline before retiring for the night. Communities and individuals who pray the Divine Office in this fashion carry out the words of the Psalmist: “Seven times a day I praise thee for thy righteous ordinances” (119:164). All clerics and religious make a promise to pray the Divine Office, also called the Liturgy of the Hours, in some form. I can tell you that the rhythm for a diocesan priest is far less structured and in the morning includes a large cup of coffee, which would probably not be very well appreciated in a monastery.

Ahead of my ordination to the diaconate, one of my scripture professors offered my seminary class a reflection on the Divine Office, to frame the prayer that we would soon promise to pray for the rest of our lives. He invited us to consider how, in the ancient world, as referenced in today’s Gospel, the night was divided into several “watches”. The Roman military kept the first watch from sunset until 9 P.M., the second until Midnight, the third until 3 A.M., and the fourth until 6 A.M. Now, he pointed out, in at least a half dozen places in scripture, the time of God’s action is decidedly during the fourth and final watch. For one, we just heard Saint Matthew’s account of Christ walking on the water, which took place “during the fourth watch of the night.” Earlier, in the Book of Exodus, the People of Israel are pass through the parted waters of the Red Sea also during the fourth watch, as the waters come crashing down upon the Egyptians at daybreak. Matthew seems to be intentionally drawing a connection between the two events. Then, later, the same evangelist will tell of how Mary Magdalene and the other Mary went to see the tomb “as the first day of the week was dawning,” placing Christ’s Resurrection as occurring also during the time of the fourth watch. Finally, and most significantly, the Book of Revelation calls Christ “the morning star” (2:28) and the Gospel of Luke “the rising sun” (1:78), meaning that as Christians our expectation for the return of Christ in glory is at the end of the fourth watch, the last before dawn. It’s for that reason that Christians from antiquity prayed facing East, as going out to meet Christ the Lord, who comes to them truly (!) in the Eucharist and symbolically with the rising sun.

My professor’s point was for us to see the Divine Office as the Church’s division of the day as complementing the ancient division of the night, which the Bible sees as leading toward the triumphant return of Christ. The Divine Office, then, is that prayer by which we ‘keep watch’ during the day, so that when we return to sleep, we will be prepared to greet Christ in the morning sun. The antiphon for Compline or Night Prayer puts it perfectly: “Protect us, Lord, as we stay awake; watch over us as we sleep, that awake, we may keep watch with Christ, and asleep rest in his peace.” This is not to suggest that we know definitively that Christ will return precisely at the crack of dawn; but living according to this rhythm, by which the hours of our day are sanctified with reminders of his return, instills within us hope and rouses us to be vigilant, for we do not know the day nor the hour when he will return.

The Church came to realize, admittedly after nearly two thousand years, that the sanctification of time through routine, daily prayer would not only benefit priests and religious but, in fact, the whole people of God. The Second Vatican Council called for a general reform of the Divine Office, and the resulting edition of the Liturgy of the Hours is far more accessible to the laity than the Roman Breviary was before. There is a free app called “Divine Office” that puts each day’s hours on your smartphone or tablet; Bishop Barron’s Word on Fire now prints a monthly edition, like the Magnificat. Consider incorporating one, maybe two, of the offices into your daily prayer. They take only 5 to 10 minutes each and can do much to fill you with a deeper awareness of God throughout your day.

Yet the Divine Office is not the only way. We build churches and shrines to sanctify space, so that when we are in them our hearts and minds are directed toward God; we put within them bells to also sanctify time. When church bells ring, the Kingdom of God is announced, calling us to remember that all time and all the ages belong to him, the one and only who is “the same yesterday, today, and forever” (Heb. 13:8). Each peal, each quarter-hour chime pulses divine grace anew into our world. When we hear the bells ring from our churches, may we be reminded that our day is sanctified by the abiding presence of the ever-living God.

Returning to the watches of the night, it is worth noting in conclusion that God’s preferred time of action coincides with the darkest portion of the night. It is when it seems least likely that God will intervene that he comes storming in. God constantly defies our expectations and surprises us when the shower of his radiant light breaks through the darkness and shines upon us. Cultivating and deepening our daily prayer reassures us that the night always has an end, for Christ is the morning star who never sets; and the Church’s liturgy ever and fervently prays for the coming of that blessed day which will have no end.

Homily preached August 12/13, 2023 at Saint Thomas Aquinas, Hampden and the Cathedral of Mary Our Queen