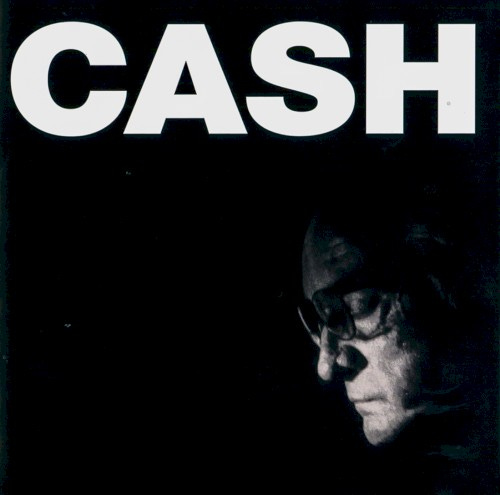

The final studio albums of Johnny Cash’s storied career include covers of several songs with which Johnny presumably felt a strong, personal connection: songs others had written that spoke to his checkered past that also expressed his hope, in the last years of his life, to still find salvation. This period in Cash’s music is, in my mind, deeply religious, reaching up from the pits of human misery in search of a hand to pull him out.

Take for example the song “Personal Jesus”, which Cash includes on the album American IV, released in 2002, the year before he died. Our narrator – in this version, Cash himself – says that he wants to be another’s own personal Jesus / Someone to hear your prayers / Someone who cares… / Someone who’s there. Johnny Cash does not want to be Jesus as much as he wants someone to need him as if he were, and the desire to be needed is as human as any. Yet, just as human is our desire to have our own personal Jesus: someone to hear our prayers, someone who cares, someone who’s there for us.

I should be safe in assuming that everyone here today realizes that only the real Jesus can measure up to that mark. No hand but his can truly pull us out of the pit. What else are we after, here in church on a Sunday morning, but to find the Jesus who is there for us?

You may not know Johnny Cash or the song with which I have opened this homily in an attempt to grab and keep your attention. Regardless, somewhere in your Christian lives I wager you’ve been told that you should pursue and build a personal relationship with Jesus Christ. We preachers have been known to throw that expression around with reckless abandon in recent years. I’m sure I’ve done it a few times myself. But on this Sunday that Pope Francis has set aside yearly as the Sunday of the Word of God, we should allow God’s Word to convict us otherwise. Scripture counsels us this morning not to pursue a personal relationship with Jesus, because there is simply no such thing.

Now, before you start hurling hymnbooks at me, allow me to say what I mean by personal. Personal indicates a closed circuit, a close hold concealed from and impervious to outsiders. Writing personal on an envelope tells the secretary not to open it. Asking about another’s finances is impolite because, they’ll tell us, that’s personal. A personal relationship is an exclusive one, and a personal relationship with Jesus Christ would aim to have Jesus all for myself and only on my terms. The Christian life is, without question, about relationship with Christ, between my person and his, but this kind of one-to-one relationship is not the kind he’s willing to make.

We see the kind of relationship Christ does want to make in today’s Gospel. Jesus calls Simon and his brother Andrew. Then, he calls James and John. Soon, he will call others, and they all will join his ever-growing company of disciples. At no point does Jesus call any of them by themselves, as individuals, to anything personal. Christ’s call is always communal: to relationship with him lived through their relationship with each other. Christ does not call us to a personal relationship with himself alone. Rather, since he has brought others into himself, relationship with him necessarily means relationship with his Body, the Church. The only right way we should speak about a personal relationship with Jesus Christ is in communion with his Church.

Where this is lost and our relationship with Christ becomes exclusive, division and rivalry ensue. We find it already in the early church at Corinth, referenced by Saint Paul in today’s Second Reading. Paul addresses the report that the Corinthians have divided themselves into opposing camps aligned beneath those whose missionary work had passed through their city: Apollos, Cephas, and Paul himself. Now, these missionaries have come and gone, but in their wake, we find a fractured Christian community divided across presumably partisan lines. It is not hard to imagine that those who thought one way started saying, I belong to Paul, while those who were of different minds said of themselves, I belong to Apollos and I belong to Cephas.

It is not hard to imagine because factionalism in the life of the Church is far from a merely first-century problem. Divisions run as deep as ever within the Church today. For Paul to write to us in 2023, he would need only change the terms: We do not claim allegiance to Paul, Apollos, or Cephas, but to John Paul, Benedict, or Francis. We ally ourselves with the bishops with whom we agree, with the parishes which measure up to our standards, and with the priests who say the things we like to hear. We hedge camps in every corner of the Christian life, from what language in which the Mass should be said to what extent Christ actually wants us to serve the poor. And through it all, we pursue a personal relationship not with the real Jesus, but with the Jesus of our own making, who ends up looking curiously similar to ourselves and those with whom we share the same mind. And if that were not enough, we hurl every unchristian thought, word, and deed out like grenades from our self-made bunkers into all the foxholes on the wrong side of the war, toward those who have done just the same.

To the Corinthians and to us, Paul asks: Is Christ divided? Should we answer the Apostle, No, he will certainly reply: Then why are you? Later in the same letter, Paul will speak about the great diversity of gifts the Spirit distributes to the Church and how each member of the Body must do their own part. What binds the parts together, what allows for preferences to coexist peacefully, what facilitates fruitful argument, Paul tells us, is love. Love must reach across the aisle and reduce to rubble the barricades behind which we have sequestered ourselves away. For the Body of Christ is called to enact the same love given by Christ the Head. Of that love, Paul writes to Ephesians: For he is our peace, who has made us both one, and has broken down the dividing wall of hostility. Christ is not divided, and by his grace we shall not be either.

Unity in the Church must be a priority for us all, for there is much at stake. In the midst of the world that sits in darkness, the Church is called to shine brightly with the light of Christ for all to see. Only in Christ do divisions cease. Only in Christ is communion with God and with each other possible. What witness to that truth do we give when we bicker and slander, malign and maltreat like everyone else and still call ourselves Christians? We give no witness at all, but a counter-witness that emaciates the good witness of those who take the Christian life seriously.

We cannot have our own personal Jesus – the Jesus of our liking – but only the Jesus who has identified himself with his Church, in all her members. If we do not love his Church, we do not love him; and if we do not love him, we will be left in our pit of misery and not find the salvation for which we and the world thirsts. Every celebration of the Eucharist invites us to deeper communion with Christ, a personal relationship with him and his Body. In this Eucharist and in every, may Christ grant us, his Church, unity, love, and peace.

Homily preached January 22, 2023 at the Cathedral of Mary Our Queen