The 20th century philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein once wrote that: the limits of my language are the limits of my world. He meant—at least in one meaningful way—that what we lack in language we also lack in understanding, and so sometimes without the right words, life becomes confusing. I am going to return to these ideas in a few moments.

The doctrine of the resurrection emerged slowly over the course of salvation history. There is a mention in the Book of Daniel of some kind of resurrection: And many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, and some to shame and everlasting contempt (12:2). The prophet Isaiah talks about resurrection in an early prophecy: Your dead shall live; their bodies shall rise. You who dwell in the dust, awake and sing for joy! For your dew is a dew of light, and the earth will give birth to the dead (26:19). The clearest statement about the resurrection in the Old Testament is found in the Second Book of Maccabees which we hear today in our first reading: It is my choice to die at the hands of men with the hope God gives of being raised up by him; but for you, there will be no resurrection to life.

But there is no talk of resurrection in the first five books of scripture, which is why some of the Sadducees denied the possibility of resurrection and so confront Christ in today’s Gospel. What the Sadducees identify is the reality that there is more ambiguity in scripture regarding eternal life and what eternal life looks like than we probably think. For the Sadducees, the absence of clear teaching regarding eternal life in the Torah meant that there is no such thing as eternal life. A different but related question also runs throughout the history of salvation: what parts of a human life will receive the gift of immortality? What I mean is the distinction between body and soul that courses throughout the whole of scripture. A prophecy in the Book of Ezekiel tells us at one point that behold, all souls are mine; the soul of the father as well as the soul of the son is mine: the soul who sins shall die (18:4) while in another passage Ezekiel speaks of a valley of dry bones returning to life (37:1-10). In the Book of Ecclesiastes, we hear that the dust returns to the earth as it was, and the spirit returns to God who gave it (12:7). And Christ himself warns in Matthew’s Gospel: Do not be afraid of those who kill the body but cannot kill the soul (10:28). So, what gets saved: the soul or the body? Or if it is the case that both get saved, when does it happen? And how? And maybe we ought to ask what matters more: the soul or the body?

From the very beginning of the Church, Christians have professed an uncompromising belief in the immortality of the soul and the resurrection of the body. St. Paul wrote to the Corinthians that: For this perishable body must put on the imperishable, and this mortal body must put on immortality (1 Corinthians 15:53). The immortality of the soul must be extended to the body, and we believe that there will come a moment in history when the dead will be resurrected to life. But notice the limits of our language: we commonly talk—almost by default—of two different kinds of eternal life. A hard disjunction is established between the body and the soul; one is perishable and the other imperishable; one lives as a victim of the brokenness of the world while the other endures as the promise of eternity. The soul becomes different from—separated from—the body, and now we are left wondering how the soul and body relate to one another.

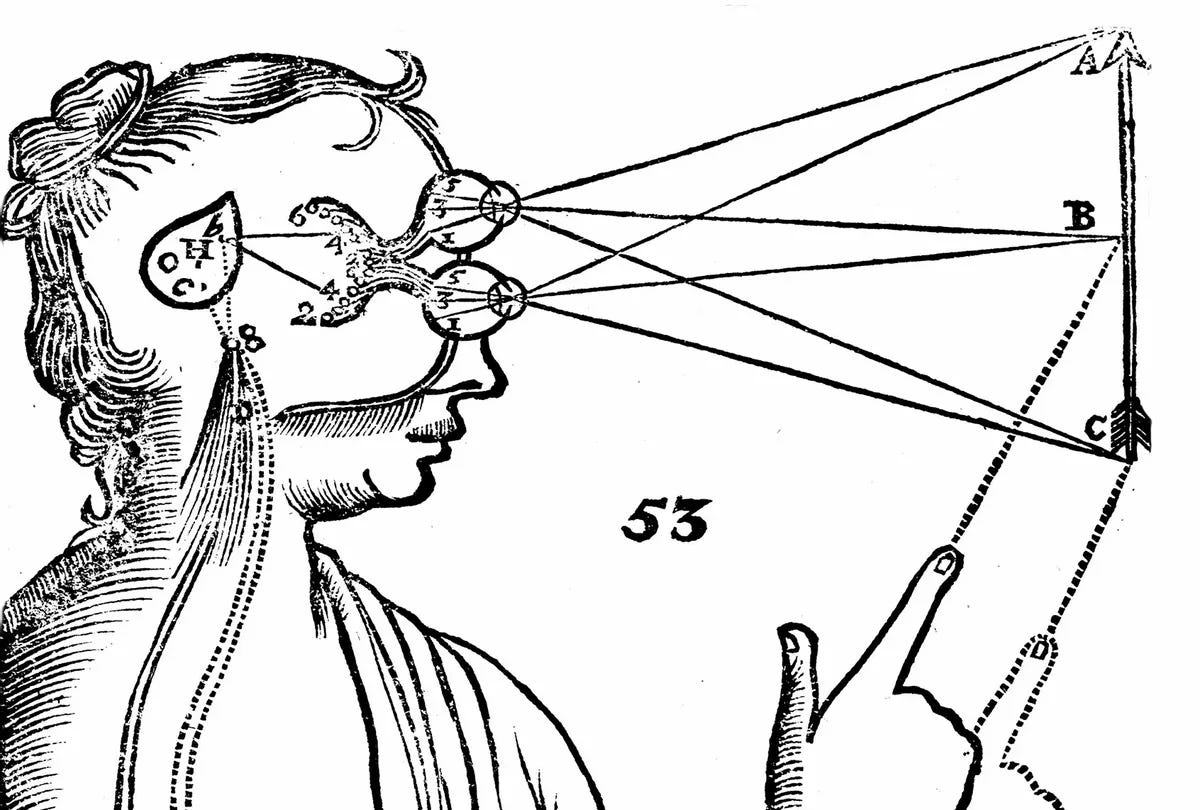

The disjunction between the soul and the body became more exaggerated by way of the theology and schools of spirituality that developed in the first centuries of the Church. Making use of a worldview inherited from Greek philosophy, spiritual masters of the ancient Church often spoke of the Christian life as one of a “spiritual ascent” to the heavens, the movement of the soul away from the body, striving ever more passionately toward union with God. Living Christianity well required leaving the body behind so that we might no longer live as a victim of the flesh and its corruptibility. The disjunction continued in the early modern period within a culture becoming increasingly secular: something called the mind-body problem became a major point of philosophical investigation. But the mind-body problem is more than philosophical; it is a religious problem, a theological problem. How does what is spiritual relate to what is physical? Rene Descartes argued that the soul—the mind—is found within the pineal gland of the human brain, and there our soul resides as the conductor of our physical bodies. The Irish philosopher George Berkely advanced a philosophy of immaterialism: there is no such thing as the physical world; we live in our minds, our souls, and the world around us is an illusion of perception. And then, of course, came generations of philosophical and scientific materialists: some socialists, some evolutionary biologists, some good old-fashioned skeptics, all claiming that the immaterial—the soul, the mind—is a fiction. We are only our bodies, and there is no room for talk of God or immortality in human life.

What I want you to understand—what I want you to see—is that we human beings have always struggled to talk about the relation between the soul and the body, the mind and the physical world, the material and the immaterial. Let me be clear: one reason we struggle is because the soul performs a function that the body cannot perform: the soul is our principle for eternal life. Eternal life matters a great deal. And so, our bodies at first receive less attention, and then are viewed as the part of human life that is the source of corruption and sin. The spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak, Christ warns in Matthew’s Gospel. There, again, is the disjunction between soul and body. The body, at best, becomes something of a nagging theological afterthought, and at worst becomes the principle of brokenness and vice in our lives.

But the struggle to talk about the relation between the soul and the body is also one of language. We do a very poor job of talking about our human lives, most of the time. Because of our great capacity for self-awareness, we can say something as meaningful as: “my body.” We all use the expression, and so it ought not surprise that the phrase then becomes politicized: my body, my choice. There in our language we find a justification for many forms of evil: abortion, issues regarding human reproduction and family planning, sex reassignment surgeries, the use of drugs and alcohol, even a classic deadly sin like gluttony. The way we talk drives home for us a disjunction between the soul and the body and so the body becomes a personal possession, something that is “ours,” to be used as we—the “person inside” who we really are—see fit. A whole system of rights and privileges is established—built into the political order—that guarantees a space for personal freedom and autonomy. Over the territory of our bodies, each of us lives as sovereign.

There is only one real problem with the politics of bodily sovereignty: our bodies are not something that we have; our bodies are something that we are. We are our bodies. The soul alone—the mind by itself—is not who we are. We are not the eternal conductors of a bodily vehicle good for 80-some years and 300,000 miles provided we do a good job with spiritual and physical maintenance. What God gives us is a human life—an integrated and complete human life. Can we speak meaningfully about one part of the life we have been given without talking about the other parts? Yes. Of course. Just as we can talk about the organ system without saying a word about the skeletal structure of the human body. But the disjunction between soul and body is a fiction of human language, a fiction of human language that is able to seize control of our human lives with the same tenacity that leads a child to believe in Santa Claus or the Tooth Fairy. Just because we can speak about something meaningfully does not mean that it exists.

Christ tells us in the Gospel today that we are a people who believe in the resurrection. The resurrection of what? Christ mentions neither the soul nor the body. And this is because Christians believe in the resurrection of human life—integrated, whole, and complete human lives. Our theology of the resurrection is profoundly impoverished in the Church today. The default understanding of too many Christians goes something like this: when we die the souls of the just get saved, the souls of the unjust get condemned, and sometime later—somehow—the souls of the just get their bodies back, but that part isn’t really important because the soul is already saved. And beyond that basic framework of salvation, we don’t do much thinking. But the basic framework of salvation for too many Christians is wrong. St. Paul teaches us that:

Are you unaware that we who were baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death? We were indeed buried with him through baptism into death, so that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might live in newness of life (Romans 6:3-4).

There is no distinction made between the soul and the body in St. Paul’s teaching. And St. Paul does not teach that when we die, the soul receives the gift of eternal life while the body is left behind to await its own gift of eternality. What St. Paul teaches is that through the sacrament of baptism a whole, complete, and integrated human life—body and soul—is so deeply united to the life of Christ that we die with Christ and are raised from the dead with Christ. Salvation happens at baptism, and salvation happens to the whole person. We spend our lives expressing the promise of our baptism, giving voice to the newness of life we have received through Christ, living as the new creation that we have become. And some of us express the gift of salvation well, and some less than well. Some Christians cherish the newness of life received through baptism, while others squander it. And at the moment of death, we will be held accountable for what we have done with the newness of life that we were given; God will honor the choices that we have made. But what gets saved or condemned is the whole person—a body and a soul that will experience a separation at death that did not exist in life, a body and a soul that for a time await the eternal union promised through baptism.

Here is what I want you to know: the human person is a mystery up against which language reaches its limits. The limits of our language are the limits of our world, and therefore there are mysteries in life—divine realities that surpass our ability to understand. St. Thomas once said that:

the soul devoid of its body is imperfect . . . the soul, since it is part of man’s body, is not an entire man, and my soul is not I; hence, although the soul obtains salvation in another life, nevertheless, not I or any man (1 ad Corinthians 924).

We are not our souls and we are not our bodies—we are human persons possessed of a body and a soul. The soul without the body is incomplete, and the body without the soul is likewise incomplete. Our souls might live eternally after death, but we do not live eternally until our souls and bodies are reunited at the resurrection from the dead. You should want your soul to be saved, but you should also want something greater: your salvation, the resurrection of your whole life—body and soul—from the dead.

These matters of theology and philosophy and language are important. There is much confusion in the world today—in our culture—about the human body. Most people today see the body as something that they have, as so much raw material to be shaped and sculpted or used or enjoyed so that who they really are on the inside might live a meaningful and fulfilled life. Most people in the world today—ironically, even many of the materialists out there who deny the existence of the soul—possess a vision of human life that is fully disembodied: who we are is on the inside, an interior reality, to which our body either conforms or fails to conform. And what we need to know—what we need to accept—is that our disembodied Christianity is no longer serving the culture. I had a professor in seminary, a moral theologian, who once told me that he wishes that we would simply stop talking in the Church about saving souls; we need to start talking about saving persons—whole and complete human lives. I loved his comment at the time because of its novelty. But the limits of our language are the limits of our world, and in our world today there is much violence committed against the dignity of the human person—body and soul. Maybe we need to start speaking with more clarity about what we believe as Christians.

Homily preached on November 5th/6th at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary

very interesting. addresses questions that have always been unclear to me.