So, Jesus said to the Jews who had believed him, “If you abide in my word, you are truly my disciples, and you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free.”

What is the truth that will set us free? There are many answers to the question because freedom is a complex reality, a reality that engages the whole of our human lives. Our Gospel today gives us one answer to the question. The Gospel today reveals to us a single truth that will set us free.

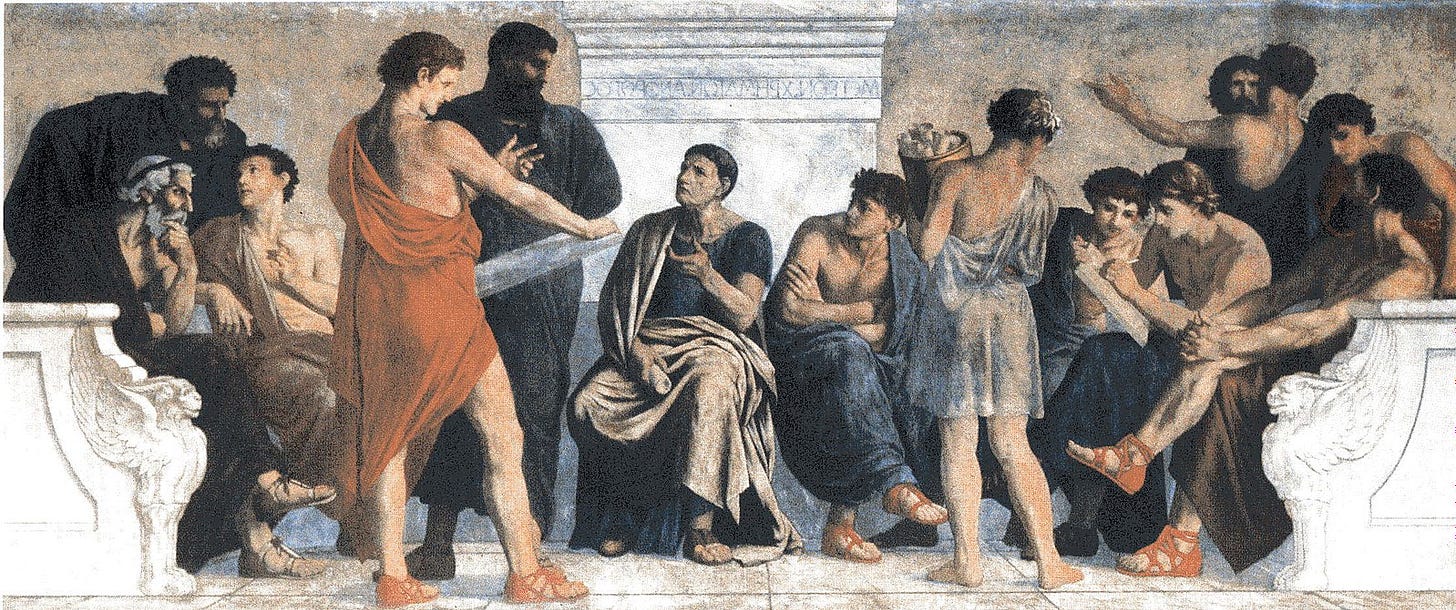

Christ gives us two characters in his parable. We are given two images of human beings at prayer, and even the posture of each person tells us something about how we are called to relate to God. The first man—a pharisee, a supposed man of God—takes up a position in the temple that he considers his own. He holds his head up high. The second man—a tax collector, a supposed sinner—stands off at a distance, as though he has entered a place where he does not belong. He keeps his head bowed low; he will not “even raise his eyes to heaven.” The first man—the pharisee—offers a prayer to God that is not even a prayer. He recites a list of possessed virtues. His ‘prayer’ is an invitation for God to notice his own excellence. The pharisee offers a prayer that is supposed to distinguish him, to mark out how he is different—better—than other believers. The pharisee pursues virtue because he desires self-perfection. The second man—the tax collector—examines his life and finds only sin; he finds no virtues worth mentioning in prayer; he finds within himself only an absence of God. He beats his breast and begs for God’s mercy. And through the gesture the life of the tax collector becomes an empty space for God to fill. There is a lesson here: no one whose ultimate goal is his or her own perfection will ever find God. We do not find—earn—perfection. We receive perfection when we allow God, who is perfect, to fill our emptiness. And so, the moment at which a Christian acknowledges his or her own emptiness becomes genuinely life-giving. We call that moment ‘humility,’ and recognize that humility is the most distinctive Christian virtue.

My guess is that most of us have learned the lesson of the parable. My guess is that most of us embrace the TRUTH that we are broken, sinful creatures who experience redemption only through the love and mercy of a self-sacrificing God. My guess is that most of us know that humility is the necessary disposition for real Christian discipleship.

We are confronted with a question, then: if most Christians embrace the TRUTH that we are broken, sinful creatures standing in need of redemption, and if most Christians understand that humility is the necessary disposition for real Christian discipleship, why are there so many problems in the Church? From where does the judgment, the envy, the jealousy, the rivalry that harms the Christian community come? If we are aware of the TRUTH of our own emptiness, ought we not pray by way of standing off at a distance, with our heads down, merely offering to God the state of our own desperation?

Let me give three answers to my question. Here is the first answer: sometimes we know something is TRUE, but it does not matter as much to us as some other TRUTH. We give preference to what we know. We rank TRUTHS. And maybe it should not surprise us that the TRUTH we make less important is the TRUTH about our own emptiness. Here is the second answer: sometimes we know something is TRUE but we cannot act on the TRUTH we know. We cannot make the movement from what is TRUE to what is good. There is a virtue called humility, and we know humility is essential for the Christian life, but we just aren’t good at living humble Christian lives. We try to live humility; we strive to live humility; we fail to live humility.

Here is the third answer: politics. And by the term ‘politics’ I do not mean the news cycle that consumes our modern lives. By the term ‘politics’ I mean the reality that we cannot spend our lives standing off at a distance in a temple with our eyes cast to the ground acknowledging our own emptiness. We have work to do. The vicissitudes of life require us to leave the temple and form relationships—to live within a society—with our eyes raised and our posture upright. But as soon as we leave the temple and enter the world, we recognize two realities that constrain us: some people rank TRUTHS differently than we do, and sometimes the TRUTHS that people cannot act upon in their moral lives are different from the TRUTHS that we cannot act upon in our moral lives.

Some people possess different values than we possess. Some people possess different strengths and weaknesses than we possess. There is a difference between what matters most to us and what matters most to other people. There are virtues we possess that others lack, and virtues that others possess that we do not have for ourselves. So it must be the case that some people know the TRUTH better than others. And it must be the case that some people are better than other people. Politics (the reality that we share our lives with others in a world with defined limits and finite resources) seems to require us to judge, to critique, to evaluate, and sometimes to condemn. And here is the real problem: because political life is a necessary TRUTH about the world in which we live, we come to believe that it is the TRUTH that requires us to judge, to critique, to evaluate, and sometimes to condemn. We build up a world of division and denunciation for the sake of the TRUTH.

Suddenly, we have arrived at the point of departure for today’s Gospel: Jesus addressed this parable to those who were convinced of their own righteousness and despised everyone else. I cannot think of a better description of political life as we experience it today. Our passionate regard for the TRUTH takes the form of self-righteousness—a self-selection of ranked TRUTHS, all justified somehow through an appeal to scripture or tradition or whatever other source of moral authority we identify. We judge, we critique, we evaluate, and sometimes we condemn. Many of us come to despise others, at least in certain moments or situations. Judgment, envy, jealousy, and rivalry becomes operative norms within the life of even our Church. And we justify our viciousness on the grounds of the TRUTH: regard for—love for—the TRUTH demands that our political lives sometimes allow for whatever manner of viciousness is necessary for doing what is right.

There is only one problem with that kind of vision of the Christian life: the TRUTH is a person, Jesus Christ, who tells us in our Gospel today that we cannot live that kind of life. We cannot. Will political life at times require us to judge, critique, evaluate, and sometimes condemn? Maybe. Political life is hard. But our regard for the TRUTH cannot become a license to ignore or to violate the teachings that Christ gives us. And the stakes are very high: we can only travel so far down the road of judgment, criticism, evaluation, and condemnation before we no longer see ourselves as broken and desperate, begging Christ to fill us with his divine life. There comes a point at which politics causes us to forget our own emptiness. We start to come to the temple with our heads held high. We take up a position in the temple that we consider our own. ‘Prayer’ becomes a recitation of our own virtue. ‘Devotion’ becomes a matter giving voice to our own judgments, critiques, evaluations, and condemnations.

The consequence is a loss of freedom. Freedom is relationship with God, and relationship with God requires us to allow Christ to fill the empty spaces of our lives with his grace. The TRUTH that will set us free is Christ. But Christ cannot fill our lives with his grace if we fail to acknowledge our emptiness. And we cannot acknowledge our emptiness when our lives are consumed by the emptiness of others. The TRUTH will set us free if we let him.

Homily preached on October 22nd and 23rd, 2022 at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary

I like the above. The homily describes beautifully a pervasive human truth.

At this time in my life, I do not feel empty (my self-analysis), but, rather, I am aware that I am not trusting enough to allow God to help me experience the childlike trust I had in God, in my parents, and in the Sisters of Notre Dame who taught me, trust that I had as a child. That may be due to a lack of sufficient humility or non-acknowledgement of sin affecting trust in God, or due to my need to be in control of real events, at a time in my life when I am not in control of events affecting me. My personal life is affected by a Mordecai (me) vs. Haman situation, as I call it. I have to pray and deliberately intend to trust God, as I trusted and loved God seemingly effortlessly and naturally as a child, and as did Judith, Esther, and Job, of the Old Testament. Dora