Here is the plan for today: I want to say a few words about a species of fish, and then a few words about making art, and then finally get to talking about the Gospel. Hang in with me and we just might get somewhere together.

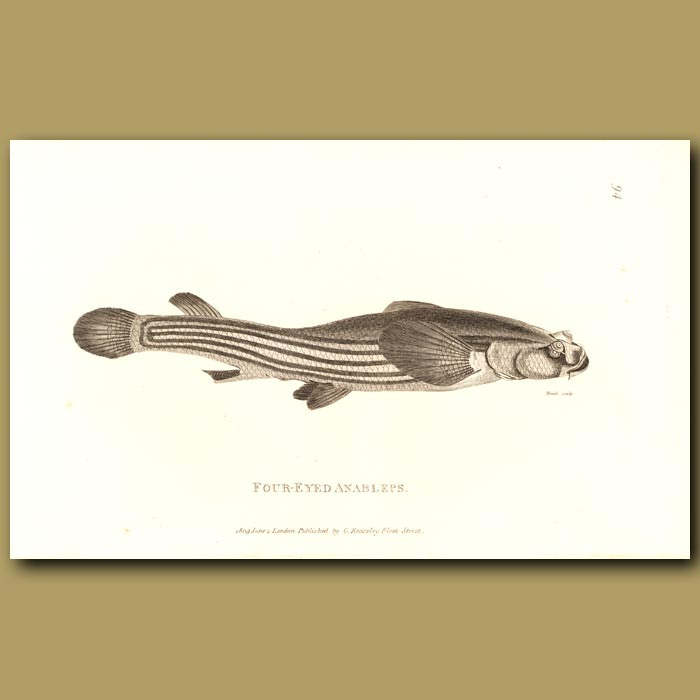

First, a few words about a species of fish. The anableps anableps is a fish found in brackish waters ranging from Trinidad to the northern coast of South America. The common name for the anableps anableps is the ‘largescale four-eyes,’ and follows from the fact that the fish seems to have 4 eyes. The biology of the largescale four-eyes fish is pretty interesting: though it looks like the fish has two eyes on top of its head and two eyes on its face (4 eyes in total), there are really only two eyes there staring at you; each eye possesses two separate lobes separated by a narrow band of tissue, and each lobe possesses its own pupil.

The Greek name for the fish (anableps anableps) comes from a combination of two ancient words: ana (meaning ‘up’ or ‘upward’) + blepo (meaning ‘to see’). The name makes a lot of sense. The fish swims close to the surface and looks like it has two extra eyes looking above, out of the water, a member of the only genus of fish in the world that can see upward.

Now, a few words about making art. The point I want to make about art is simple: no one knows a work of art like the artist who made the art. You can read books on the history of the Sistine Chapel ceiling, spend years looking at every detail of the masterpiece, even receive a PhD in art theory, and nothing you do will ever allow you to know the Sistine Chapel ceiling as well as Michealangelo knows it. St. Thomas says that the best and purest kind of knowledge we can possess in life is the kind of knowledge you get by making something. When you make something, you take an idea in your mind and you give it life, and so by making something you imitate the work of God, the creator who made all things and gave them life.

Finally, I am going to talk about the Gospel. Today we are told about the blind man Bartimaeus who asks Christ for the gift of sight, vision—I want to see, he tells Jesus. Here is the cool part of what Bartimaeus says to Christ: the Greek verb used in the Gospel is pretty much exactly the scientific name of the largescale four-eyes fish that swims in brackish waters off the northern coast of South America—anablepso, Bartimaeus tells Jesus, make it so that I am up-looking, seeing upward, having a vision of what is above me. In the Greek language in which the Gospels are written, to recover your sight from a state of blindness always carries with it the sense of looking up, above you, at what is higher, toward the source of light that makes vision possible.

Here is what we know: Bartimaeus is a man who possesses real faith, he believes in Christ, he wants to see, and recovering your sight from a state of blindness means looking up toward the light. The next move is easy for you to guess: Christ is the light, a light that shines in the darkness, a light that the darkness cannot overcome. To want to see, to really want to see the world, means to use your vision to first look toward Christ who is the light, and then to look out at the world through Christ, because only light makes real vision possible. You do not need to have 4 biological eyes or even 4 distinct pupils to possess real vision; you just need to know that real seeing means the possession of real spiritual vision, and that to possess spiritual vision means seeing reality through the light of Christ.

What I want to do now is connect the need for spiritual vision to a basic claim about human knowledge. The hard truth about human knowledge is that we did not create the world. We can read books about how the world works, spend years studying different aspects of reality, even receive a PhD in some science or liberal art, and still we will never know the world the way that God knows the world because we did not create the world and God did. God is the divine artist who creates through the working of the Word, the Word who was with God in the beginning, the Word through whom all things were made, and without whom nothing was made. Christ is the Word of God who gives life to everything that exists, who knows the world the way that an artist knows his or her masterpiece.

The only way for us to possess real knowledge about the world, to say anything meaningful about life, is to try to know the world the way that God knows the world because God made the world, and we did not. If you want to understand an artistic masterpiece, you need to see that masterpiece through the eyes of the artist who made it.

Maybe you can now understand what I am trying to say with my homily. The blindness of Bartimaeus is a physical disability that gets healed in the Gospel today, but the deeper meaning of the Gospel is that human blindness comes from not seeing reality through the light of Christ. The literal language of the Gospel today—I want to see—possesses the meaning of vision requiring someone to look upward, above, toward what is higher, toward the source of light. There is no real knowledge that you can possess unless you see reality through the light of Christ, because Christ is the artist who made the world. Without Christ, you are blind, you live in the dark, you know nothing.

To know what is true means to see reality with clarity, and there is no real knowing or seeing without Christ. We live in a world today that makes it very hard for us to know and see reality. We are told that to live as a mature person means to ‘think for yourself,’ to go out there into the world and form your own values, to decide what is right and wrong, to take a stand for whatever you decide is real; the broken logic of modernity has infected us, convincing us that we might possess real knowledge of the world without God. Even among those who make the choice to follow Christ, we know there is a problem with knowledge and wanting to ‘think for ourselves’ because there is devastating and scandalous disagreement in the Church today about what is real and what is true. We modern humans walk around the world acting like we created it and that is the deepest kind of arrogance and the consequence of pride working in us.

Here is what ‘thinking for yourself’ ought to mean, what it meant for centuries before modernity taught us to forget seeing the world through the light of Christ: you take the universal truths you receive from God about how the world works from the Church and apply these universal truths to concrete, tough situations in life as best you can. We do not get to create our own values; we do not get to decide what is right or wrong about the structure of reality or what matters the most in human life. Christ teaches us what matters; Christ teaches us how the world works. And then you go through life taking the truth that Christ gives you and you do the best you can to become a good person. You might not always get life right, you might make mistakes, you might get yourself confused about what Christ teaches or misapply a divine truth to a concrete situation and make a fool of yourself, but as long as you remember that you cannot know what is real and true without Christ, and you let the poverty of your knowledge drive you closer to the Church, you will be fine. You will never be perfect in life, and that is alright; you just can’t be a blind fool who has forgotten God.

To know what is true means to see reality with clarity, and there is no real knowing or seeing without Christ. To live without Christ means to live in a state of blindness because the world was created through Christ, by Christ, and only an artist really knows his or her masterpiece. There is no real knowledge of the world without Christ, and to want to know the world means to want to see reality through the light of Christ. When Bartimaeus cries out to Christ in the Gospel today—I want to see—he is talking about more than physical blindness because we are told that Bartimaeus is a man of faith. He knows that there is no real seeing for us, no vision, no clarity, without looking upward, above you, toward what is higher, toward the source of light that makes real vision possible.

Homily preached on Sunday, October 27th at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary