What we need to live a good Christian life has been revealed to us by God. But not everything that God has revealed is immediately clear to us. Consider a few famous examples from the history of Christianity.

Sabellius of Rome in the 3rd century taught that God is not a Trinity of persons. He thought that there is only God the Father, and that the Father appears in different modes in history, sometimes appearing as Christ, sometimes appearing as the Holy Spirit. Paul of Samosata taught around the same time that Christ is not God-become-man but rather a human being who is adopted by God for the purposes of salvation. Arius of Alexandria in the early 4th century taught that Christ is not born of the Father before all ages—Christ is not the eternal Word of God—but rather a creature made by God for the sake of creating and redeeming the world. Apollinaris of Laodicea, a few decades later, taught that Christ did not live a full human life—that he did not possess a rational human soul—but rather that the life of Christ consists of the Word of God occupying an empty human body. Eutyches of Constantinople, almost halfway through the 5th century, taught that Christ is not possessed of two natures—one human and one divine—that exist without confusion but rather that Christ’s human nature is subsumed by his divine nature, that the humanity of Christ gets lost in his divinity.

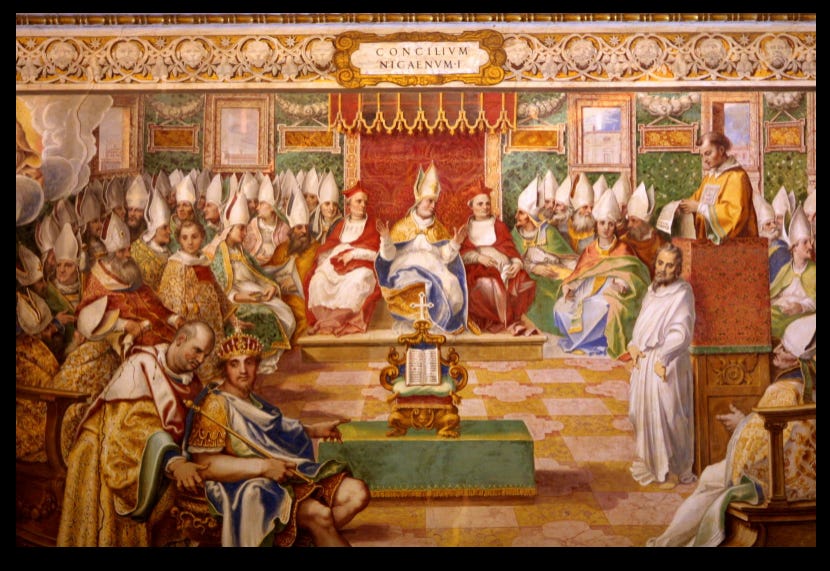

These beliefs are all heresies of the early Church. And these are heresies that came into existence because not everything that God has revealed to us is immediately clear. Within the content of revelation are the truths that God lives as a Trinity of persons and that Christ is the eternal son of God who assumes a whole and complete human life in all ways but sin, and that humanity and divinity exist in the life of Christ without confusion. But these two foundational dogmas are not immediately clear to us in revelation; we needed several centuries to get there as a Church. Which is one reason why, I think, that Christ establishes a Church in the first place: there are truths about the Christian life to which we do not possess immediate access; truths that are not so obvious, and so we sort out these truths together under the guidance of the Holy Spirit. We might wish that revelation was so clear to us that we would not need a Church to understand everything we need to know about the Christian life, but that desire would be a consequence of our pride. Our finite limited human minds cannot possibly understand the eternal revelation of God immediately, intuitively, and free from reflection, controversy, and disagreement.

The consequence of the lack of immediate, intuitive clarity within the content of revelation is opinion in the Christian life: theological opinions, moral opinions, spiritual opinions. Even among truths that are seemingly clear, immediate, and intuitive we find room for all manner of opinions on the Christian life. Most of our battles in the culture wars today revolve around matters whose truth or goodness or beauty are revealed to us clearly enough by God, and yet still we find ourselves possessed of our own opinions. We like to think for ourselves, we want to have a stake in the teachings of the Church, we insist on ranking the relative importance of various truths for ourselves, and we do not want to be told that we are wrong. And so, the Church becomes a theater for the exchange of opinion, and most of us are not happy when we are told that we need to think differently, believe differently, see differently.

For the last several days, I have been involved in an extended exchange of opinions with some of my friends regarding wealth and the Christian life. We do not agree on how Christians are called to live. We read an essay last week about the moral theology of Dorothy Day and her teaching on poverty. You see, Dorothy Day did not believe that poverty is evil; in fact, she thought that poverty is a spiritual good. While forms of destitution are a violation of human dignity, poverty helps us to live the Christian life well. To live in voluntary poverty is to make yourself dependent on God and neighbor for your welfare; the absence of comfort and security in life establishes an enormous space for relationship and community, for authentic trust in God; poverty helps us get to holiness in life, and for the Christian there is nothing more important than holiness in life. Dorothy Day called these forms of voluntary poverty living within the precarity of love: living within a vulnerability in life that binds us to the work of love.

The point of my homily today is not to tell you all to go live a life of voluntary poverty like Dorothy Day. I admit to you that I am deeply sympathetic to her teaching and to the witness of her life. But the counterfactual to voluntary poverty is obvious enough in the history of the Church: Hedwig of Poland, Stephen of Hungary, Ferdinand of Castille, Edward the Confessor, Elizabeth of Portugal—these are all saints of God who knew wealth and privilege in their lives; and there are many others. A camel might pass through the eye of a needle with more ease than a wealthy person will enter the Kingdom of God, but at least some camels seem to make it through unscathed. Living within the precarity of love makes sense to me. And I think that we desperately need that kind of Christian witness in the world today. But no one can say that salvation is impossible for the wealthy and the privileged; after all, with God all things are possible.

The life of voluntary poverty and the precarity of love are not the point of my homily today. What is the point of the homily? The point of the homily is to get at the burden—the cost—of personal opinion within the Christian life. For weeks now, we have heard Christ preach about wealth in the Gospel of Luke. Last week we were told that we cannot serve both God and mammon; the week before we were told that wealth allows the prodigal son to live a life of dissipation; the week before that we were told that anyone who does not renounce all of their possessions cannot be a disciple of Christ; earlier in the summer we were told that much will be demanded of the person entrusted with much and that we must guard against all greed because though one may be rich, one’s life does not consist of possessions. The theme of poverty—yes, a poverty in spirit but also financial poverty, a poverty in regard to possessions—courses throughout the whole of Luke’s Gospel. And each week we hear the Gospel drive home these same themes again and again and we each form our own opinion about the meaning of the Gospel. We do not agree on what we are supposed to do—how we are supposed to live—in response to Christ’s teaching.

And what I want to say in response is: there is nothing wrong with our lack of agreement or diversity of opinion on money and wealth and the Christian life. The teaching of Christ on these matters is not immediately, intuitively clear to us. Poverty in spirit seems to be more important than poverty in possessions; some camels seem to get through the eye of the needle just fine. But there is a burden—a cost—to personal opinion. The uncomfortable and disquieting reality is that not all personal opinions are correct. There is a standard for the Christian life; we call that standard ‘truth.’ And as Christians we know that a time will come when we confront Christ and are asked to give an account for the choices we have made. And like the rich man in today’s Gospel, we might claim that we are shocked and surprised to discover that our personal opinion about wealth and privilege was wrong. When did I see you hungry, Lord, or thirsty, or a stranger in need of housing, or naked and needing clothes, or sick and needing care? And we might say to Christ: Lord, I did not know how to live . . . the Christian life was not so clear to me . . . if only you would send someone to warn my family. And Christ might say to us: if they will not listen to Moses and the prophets—if they will not be persuaded by the Gospel you heard week after week after week—neither will they be persuaded by the messenger I would send.

There is remarkable space for opinion in the life of the Church: theological opinion, moral opinion, spiritual opinion. What we need to live a good Christian life has been revealed to us by God. But not everything that God has revealed is immediately clear to us. And sometimes we do not agree with the truths that are clear to us, and find a way to create even greater space for opinion in the life of the Church. But there is also a burden—a cost—to personal opinion: we might be wrong.

Homily preached on September 25th, 2022 at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary

How should we discern the right, if it is not clear in revelation?