Saint Augustine once said, “If we pray rightly… we say nothing but what is already contained in the Lord’s Prayer.”[i] Augustine saw within the seven petitions Christ taught his disciples to pray the whole breadth of Christian prayer: no true prayer for Augustine could extend beyond what we dare to say when we ask Our Father to sanctify his name among us, to inaugurate his kingdom, and to accomplish his will; to give us our daily bread, to forgive us, to save us from being led into temptation, and to deliver us from evil. We may use other words to give our requests a more definite form, but everything for which we pray—and could pray—is already contained in the words our Savior gave us.

Writing in the 20th century and finding agreement with Augustine, another spiritual writer described the full vista of prayer held within these petitions in this way: “Beginning on the summits of our experience, with the most sublime invocation of Reality possible to man, they end with the creaturely confession of our utter dependence and need of rescue and guidance. Taken together, they exhibit the richness and suppleness, the spiritual realism, of the Christian life of worship.”[ii]

Both authors, ancient and modern, consider the Lord’s Prayer as speaking to every facet of reality. More specifically, in their view, the Our Father speaks to the full range of our human experience of reality, to what we feel viscerally every day. The Our Father possesses the capacity to gather up our joys and our sorrows, our hopes and our anxieties, and voice them to the Father in one prayer of adoration, contrition, thanksgiving, and supplication.

But there is a deeper dimension to this prayer, and to Christian prayer in general, that we ought not to overlook. The Lord’s Prayer not only enables us to process reality; but even more, prayer is the only possible way of truly engaging it. Prayer is not the spiritual equivalent of ibuprofen to help us manage our experience as we might take two Tylenol to soften a headache; rather, prayer is the very point of entry to plunge into reality itself, not to escape or mitigate its brutality, but to face it.

Part of what I suspect stands behind the decrease in church attendance across denominations in the past several decades is the presupposition that Christian faith has nothing to say to reality. For one of the values that is most highly valued in contemporary society is realism, not idealism. What undergirds debates in parliaments and public squares are not philosophic musings on the nature of reality and its implications for life but the real, lived experience of people, particularly those who suffer under one form of injustice or another. To truly address them, it is alleged, one must not retreat to speculative discourse or take shelter in the false comfort of a creed but face their harsh reality head-on. In the wake of a tragedy, anyone who is not overtly committed to real and tangible change but instead offers the vapid sympathy of thoughts and prayers is quickly written off as a fool.

Prayer is considered to be wholly disconnected from reality and thus dismissed as personal piety that does more to make oneself feel better in the face of suffering than to actually confront it. Saint Augustine (and the whole Christian tradition behind him), however, would have found such an appraisal not only unfortunate but also deeply misguided and, in fact, detrimental to the clear and noble good pursued. For the Christian, prayer is the only true point of entry into reality because reality can only be understood from within the One who created it; and the One who created all that is visible and invisible, the earth and the heavens, has entered into the reality of his creation, has lived every point across the spectrum of human experience, and gave those who believe in him the capacity to see for themselves the true meaning and purpose of all that is.

The seven petitions of the Our Father are not the product of a human heart searching aimlessly in the darkness to paint some indistinct and incomplete picture of reality. No, it is the prayer of God himself, who took to himself a complete humanity, and in that humanity lived the full breadth of the human experience and from his human heart gave and taught his disciples words to express the fullness of their humanity to God our Father.

We need only look to the Gospels to see what Christ experienced, and that which forms the content of his prayer: his birth in oppressive and dangerous circumstances; his hidden life in Nazareth where he learned his earthly father’s trade; his temptation in the desert and his abandonment in the Garden; the following his preaching accrued and the rejection it caused him to endure; his delight at making the lame to walk, the blind to see, the deaf to hear, and his agony at all the greater multitude his earthly life withheld him from healing; the death of his friends and the foreknowledge of the certain martyrdom of his disciples; and his own ruthless torture and death and descent to the realm of the dead, all vanquished by the victory of his resurrection; and the joy it brought him to send his disciples into the world to proclaim the Gospel to every creature.

It is in light of the life he lived, which spans the gamut of human experience, that he tells his disciples, “When you pray”—when you turn to your Father to make sense of the reality you experience—say, “Father, hallowed be your name.” Paul says that in baptism we were buried with Christ and were also raised with him into new life. Christ has incorporated our lives, our existence, into his, and thus does his prayer become our own; we can truly speak his words which express and make sense of his reality to make sense of our own. We can truly call God “our” Father because we are one with Christ, the Father’s eternally begotten Son.

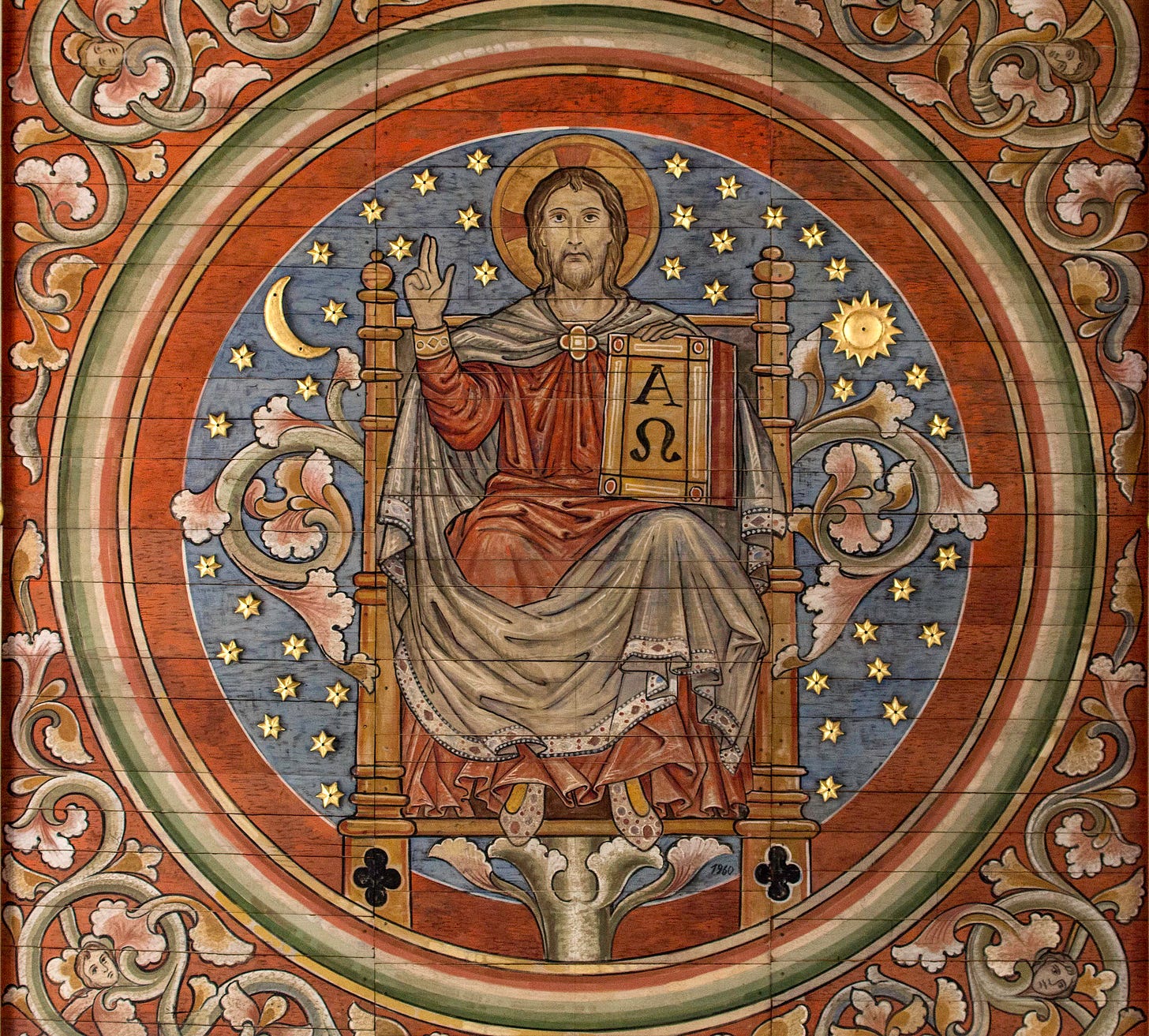

Because Christ alone entered into and embraced reality fully, he alone can truly understand it, and he alone possesses the capacity to reveal its meaning to us. Only in Christ does creation and history, all that exists and all that will ever be, discover its calling that reaches fulfillment only in him. To be a Christian is not to bracket out human experience but to embrace it to the fullest degree possible. Only a Christian can truly be called a realist, for only a Christian has been graced to know and to love Christ who is the Alpha and the Omega, the origin and goal of all reality.

Prayer disposes us to see and be captivated by the contours of reality that Christ alone reveals. Prayer gives us entry into Christ’s way of seeing, his way of being in the world. Christ did not run from the world but ran into it to its fullest depths. Prayer makes us runners with him.

Yet the second half of today’s Gospel makes it clear that embracing reality with Christ does not abscond us from our responsibility of being committed to real and tangible effects; rather, being in Christ gives us the capacity to do so with the Godward perspective to help people in the manner that Christ himself employed. Jesus describes how the Father responds to our petitions in light of how we respond to those who petition us: “What father among you would hand his son a snake when he asks for a fish?... How much more will the Father in heaven give the Holy Spirit to those who ask him?” But we can turn this relation around and look at it in the other direction. If when we pray our Father in heaven responds in his love lavishly to the real needs we present him, how much more ought we, who know the Father’s love, respond in kind to those whose suffering moves our hearts and who cry out to us in their need? Our relationship with our Father in heaven, nourished and fortified by prayer, allows us to know how and gives us the capacity to act with the selfless love of the Father’s heart that gives everything and holds nothing back from those in need.

“If we pray rightly… we say nothing but what is already contained in the Lord’s Prayer.” May we dare to pray the words our Savior gave us with confidence and gratitude, for he has given us the words of his own heart to enter into and embrace the reality he has created and which he desires to bring fulfillment, for which he has taught us, the members of his Body, how fully and truly to pray.

[i] Augustine, Letter 110, 12:22.

[ii] Evelyn Underhill, Worship (New York: Crossroad, 1936), 224.