The reality of God dying on a cross is hard for me to imagine. I think the reality of Christ’s death is one of those truths we commit to memory, lying there in plain sight, accepted as commonplace by anyone who comes to church on Sundays, but is the kind of truth that will bring you to the limits of your imagination if you ever really try to make sense of what you say you understand.

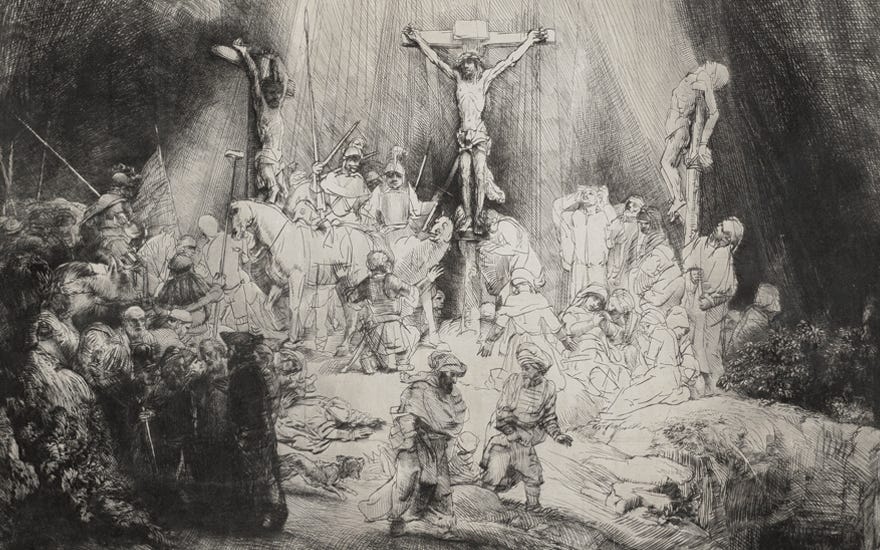

From the human side of the equation, to imagine Christ dying on the cross is not too difficult. We know what it looks like to die on a cross; we have seen plenty of paintings and sculptures and movies and live images that show us something of what that kind of death looks like. We also know what pain is, we know what fear is, we know what it is like to experience isolation and separation from the people you love the most, we know what it is like to be mocked and judged and ridiculed, and maybe some of us have come close enough to death to possess for ourselves some sense of what it feels like to see the end of your life there in front of you. From the human side of the equation, to imagine Christ dying on the cross is not too difficult: we take what we know from our personal experiences, and we build them into an image of what Christ’s death on the cross must have been like. The work of our imagination will not be perfect, but we will still draw ourselves closer to the mystery of the cross.

The problem for me, and maybe for many of you, comes from the divine side of the equation: what does it mean to say that God dies? Christ is the one who dies, and as long as we keep saying that it is Christ who dies, maybe we never put too much thought into what is happening on Calvary. But Christ is God, and from the very first centuries of the Church we have believed that whatever you can say about Christ you can say about God. So, if Christ dies on a cross, then God dies on a cross. What does that mean? How could we possibly understand how—or why—God dies for us.

The mystery runs even deeper. Christ is God and offers his life on a cross and dies, but the Father is also God and Christ is his son and the Father loves his son more deeply and more purely than we could ever imagine, and on the cross the Father allows his beloved son to die for us. What does that mean? How could we possibly understand how—or why—the Father allows his son to die for us?

Sometimes I think that the best way to make sense of the mystery of the cross is to come to terms with the extent to which we will never understand what is happening. St. Paul helps us come to the limits of our imagination. He tells us in his Letter to the Romans that for a good person someone might dare to die but that God proves his love for us because Christ died for us while we were still sinners. Imagine letting the person you love the most die for the sake of the worst person you know. My guess is that you cannot actually imagine that possibility.

Now imagine that you are eternal, all-powerful, all-knowing, that you created the world and that you do not need the world you created any more than an artist needs a painting he has made, but that you love what you have created so much that you die for your creation. Imagine an artist dying on a cross for the persons he has painted on a canvas. My guess is that you cannot actually imagine that possibility.

There, I think, coming to terms with the limits of our imagination, is how we can make the most sense of the mystery of the cross. The clearer we know how much we do not understand, the more deeply do we behold the mystery of what God is doing.

The Church gives us these readings today to remind us that during the weeks of Lent we are moving toward the mystery of the cross. Many people point out the horror of our First Reading: how could God ever command a father to murder his own son? But the real horror is that God saves Isaac from death but later offers the life of his own son so that others might live. What God did not allow for Abraham and Isaac he claims for himself and for his beloved son. The story of Abraham and Isaac shows us what God is doing on Calvary. The ram caught there in the thicket is Christ, who the Father loves but will allow to die on a cross for our salvation.

But the death of Christ is not the end of the story, and the Gospel today gives us an image of the reality that flows out from the mystery of the cross: transfiguration, resurrection, new life. The son dies on the cross but the Father does not let him remain dead. Christ is raised from the dead. His body bears the scars of human suffering but now there is no more suffering, no more pain—death no longer has a hold on Christ because the love of the Father causes resurrection and transfigurement. And we are baptized, as St. Paul tells us, into the death of Christ so that we will share in the resurrection of Christ. His death on a cross becomes ours so that we too might become resurrected and transfigured.

I wanted to give a homily on the mystery of the cross today for a few different reasons.

First, like I said, you profess a simple belief about Christ dying on a cross but how much time do we spend in prayer or conversation trying to make sense of what is really happening on Calvary? What does it mean to say that God dies on a cross? We could all spend more time trying to make sense of the mystery of the cross.

Second, the mystery of the cross becomes the mystery of our lives through the waters of baptism, so the reality of the cross gets real and personal for each of us. You are going to suffer and experience pain in your life, but the pain and suffering you experience is not purposeless and will not define who you are or determine the quality of your life. The reality of the cross is bound up with the realities of resurrection and transfigurement in the life of Christ; these realities cannot be separated from one another. And we share in each of these realities through our baptism. There is no suffering for us that is disconnected from the reality of resurrection, no experience of pain that is not a movement toward transfigurement. The reality of death is conquered on the cross, pain and suffering do not define who Christ is or determine the quality of Christ’s life, and through the waters of baptism his life becomes our life. These weeks of Lent are given to us so that we might remind ourselves of who we are in Christ Jesus.

Finally, the world needs our witness to the mystery of the cross. Someone once told me we live in a state in which each January our government gets together in Annapolis and looks for new ways to kill people. I think that is a pretty accurate assessment of where we are in the culture. We received word yesterday that there is a strong push right now to get a law permitting physician-assisted suicide onto the floor of the Maryland Senate, but the vote count is very tight, and we need to act. I am asking you all to do an online search for the Maryland Catholic Conference, visit the website, and follow the links for the Urgent Alert on physician-assisted suicide. You will be given a form letter to send to your senators and delegates asking them to vote against the bill. The whole process only takes a few moments; you can pull out your phone and do it right now if you like. Help us stop a bad law from becoming a reality.

The truth is that many people do not know what to do with the realities of suffering and pain and death. Many people identify suffering and pain and death as evil, believe that evil needs to go away, and so look for as many ways as possible to make pain and suffering go away—up to and including the legalization of physician-assisted suicide. That kind of thinking is right about the realities of suffering and pain and death: suffering and pain and death are evil, they are a consequence of sin, and sin is evil, and we should hate sin and what follows from sin with a perfect hatred.

But the realities of suffering and pain and death are not the only realities that matter. The reality of human dignity matters; the reality of God’s plan for human life matters; and the reality of the cross matters. The reality of human dignity means that each human life is possessed of a sacred value no matter how serious the pain and suffering that makes life seem a burden. The reality of God’s plan for human life matters because we have no standing to make choices about who lives or who dies and we need to get over ourselves, accept our limitations, kill our pride, and let God govern the course of our lives.

And the reality of the cross matters because suffering and pain and death do not define who we are or determine the quality of our lives. Through the mystery of the cross, the horrors of pain and suffering and death are eternally conquered by the joys of resurrection and transfigurement. Many people experience suffering and pain and death and think our best response to these horrors are laws that make them go away. That kind of thinking makes sense, but it is flawed, and often allows for greater evil.

The best response to the realities of suffering and pain and death is baptism, new life in Christ, death conquered, pain and suffering rendered impotent, a human life transfigured by the grace of God. The reality of baptism means that we can remain joyful in our suffering, joyful in our experience of pain, joyful in the face of death. Hope and joy belong to us, always, because by baptism we are joined to the saving work of Christ. And the world needs our witness to the mystery of the cross, the world needs to see our joy and share in our hope and come to recognize that the realities of suffering and pain and death do not speak the final word for any human life.

Hope and joy, those are the realities toward which we are moving during these weeks of Lent, and the mystery of the cross is how we get there.

Homily preached on Sunday, February 25th at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary