Politics have perhaps been of no greater interest to the masses in recent memory than in the ongoing debate surrounding the forgiveness of student loans. The 1.6 trillion outstanding dollars owed is a burden upon many of the 43 million borrowers it comprises. On any side of the issue (and let me make myself clear that I do not intend to take a side), what all can agree upon is that no one would rather pay the thousands of dollars they owe the federal government any sooner than is absolutely necessary. We agree because we tend to act that way when we owe a debt, especially if that debt is great. We’d rather put repayment off as long as legally possible or financially prudent than cut a check right away. Whether its twenty bucks for lunch or a mortgage, settling up with our creditors is not an obligation we cherish.

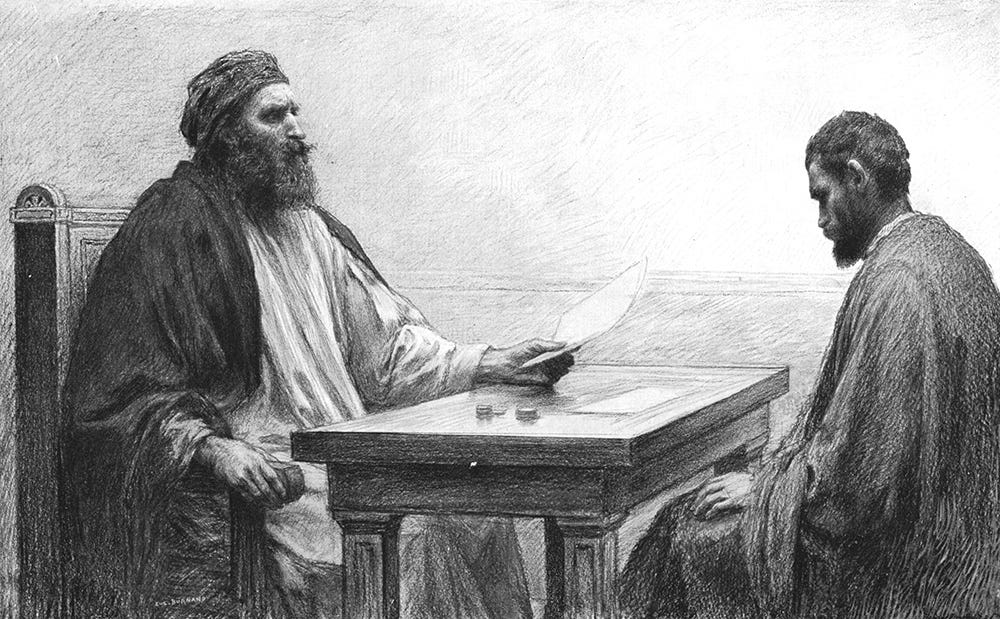

Today’s Gospel parable is about the fact that there is a settling up that we can only stave off for so long. The Gospel speaks figuratively of the account that we will have to render before our Lord of the stewardship that we have exercised in his name throughout our life. And while we may not consider ourselves dishonest, we each have more in common with this shrewd and conniving steward than we perhaps care to admit. The Greek word that is here translated as squandered implies not only that the steward misused his master’s property but, more literally, that he wasted it. His cause for termination is not that he has invested his master’s wealth for his own gain but rather that he hasn’t done anything with it at all. And when the steward is summoned to give a rational account of his stewardship, his neglect can no longer remain hidden. All he has done, and more importantly, all he has failed to do, will now be brought to light and held against him.

If it were possible to pull up an account summary of our life – of what we have done and what we have failed to do – would any of us have the courage to read it? If we did, we would see how we have failed by abandon, apathy, or outright malpractice to exercise faithful and prudent stewardship over the life that God has credited us. We would see how pitiful a return our investments in vanity have yielded. What really mattered and what was really worth our time and energy we neglected, while we obsessed and spent ourselves on all that didn’t matter in the slightest. Few of us would freely choose to read such a report now, as we shudder to think what it would say.

But at the end of our lives, all of us will not only need to read our report but we must also give a rational account of our stewardship to our Master, the just Judge, the Lord of all. When our earthly life is finished and we are no longer employed as steward, the Master will call us before himself and say: What is this I hear about you? Prepare a full account of your stewardship. Then we will have to face the man and give him an account of our life, the life he has given us on loan, free of charge. And we will have to explain to him why we have not been good stewards over the life he has given us. We will have to answer for how we have used and misused and failed to use his gifts. And in giving our account, we will all have to show how and why we have come up short. And we will all, rich and poor, in the end come up as debtors before our Lord and Master. For good reason, we would all prefer to wait as long as possible before that happens.

The Gospel parable strikes us because of its finality: the Master does not suffer any retorts. There is no court of appeal, no tribunal to change or soften the verdict. And our judgement that the parable predicts is no less final: temporal decisions have eternal consequences. What the rather bleak picture I have painted thus far is missing, however, is the fact that the balances can be reset before the final accounting is made. There is still time to cancel our debt. And the power to wipe it out has been placed, by the Master’s mercy, into our hands. He gives us, in the time that remains, ample opportunity to set our account to rights.

Saint Paul teaches us that we can offset our bad stewardship with the good and holy work of prayer. Paul writes to his dear friend Timothy: I ask that supplications, prayers, petitions, and thanksgivings be offered for everyone and that in every place the men should pray, lifting up holy hands. Paul desires everyone to pray because God desires everyone to be saved and to come to knowledge of the truth. Prayer is a cause of salvation for us and for the entire world.

But from where does prayer derive sufficient capital to offset the debt incurred by sin? Prayer is always directed through Christ, who Paul describes as the one mediator between God and men. He is the meditator because, in him, the creditor has taken the place of the debtor. He plays both sides. He is fully God and fully man. He and he alone is able to repay the debt humanity owes to divinity. And he repaid that debt to the full when he gave himself as ransom for all on the cross. And by God’s mercy, he allows our prayers to participate in the saving work of Christ, to pray through him, that we and the whole world might have our accounts zeroed and even credited before our stewardship is up.

First and foremost, the prayer that the Church offers each and every day but especially on Sundays in the holy sacrifice of the Mass is the most perfect and most efficacious prayer we can offer, for it is the prayer of Christ crucified. Time spent in Eucharistic adoration draws us more deeply into the love of Christ and consoles us with the knowledge of his continued presence and work in the Church leading his people to salvation. The lives of the saints up and down the centuries attest to the wellspring of good that is wrought from devotion, most especially devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary. Even ten minutes of quiet solitude in the presence of God wherever we find him has more value than hours spent doing what will not matter when our time is up and our accounting due. Whatever forms of prayer we make, we make them all to our benefit.

In the time that remains, whether long or short, before we are called to give an account of our stewardship, we ought to heed Paul’s charge that prayers should be offered by everyone and for everyone, that we should not squander the incomparable gift that the mercy of God has given us to wipe out our debt. We have been dishonest stewards. May we be so no longer. For our Lord and Master desires nothing more than to welcome us as good and faithful stewards into heaven to share his eternal joy.

Homily preached September 18, 2022 at the Cathedral of Mary Our Queen.

A touching heartful reminder of what we all are (we fall short), and yet of God's fantastic love.

Amo Iesu,

Dora