In his recent lecture at the Cathedral Colloquium, Mr. Samuel Rowe (Director of Music at the Basilica of the Assumption in Baltimore) made the observation that Maurice Duruflé’s Requiem ends on a dominant seventh chord and invited theological speculation as to why. This little essay accepts Mr. Rowe’s invitation and thanks him for the opportunity to think about an exceptional piece of music.

A dominant seventh chord is a major triad plus a minor seventh. Whether major or minor, the seventh scale degree leads naturally to the eighth, the tonic an octave above where the scale began. Its relation to the tonic is clear if you sing Do-Re-Mi but stop at Ti. Add that Ti into a major chord and you get a lovely, dissonant chord. A dominant seventh is very pleasing on its own but, as Mr. Rowe pointed out, it is a strange choice to conclude a piece of music. Its unresolved dissonance leaves the listener with an unsettling sense of incompletion, which I will suggest, engenders hope for future resolution or rest.

To aid my pondering, a friend – and faithful reader of Ecclesia Christi – directed me to a helpful interpretive guide through Duruflé’s Requiem, which includes the best information one can have to understand a piece of music: what the composer himself had to say about it. In his program notes for the Requiem, Duruflé wrote:

This Requiem is not an ethereal work which sings of detachment from earthly worries. It reflects, in the immutable form of the Christian prayer, the agony of man faced with the mystery of his ultimate end. It is often dramatic, or filled with resignation, or hope and terror, just as the words of Scripture themselves which are used in the liturgy. It tends to translate human feelings before their terrifying, unexplainable or consoling destiny.1

The Requiem’s closing chord, I think, reflects the earthly worries that remain with those who mourn in the wake of a loved one’s departure. To grasp the chord’s meaning more fully, we need to consider the liturgical action this chord would accompany. Although Duruflé composed the piece as a ‘concert Requiem’ and not for use in an actual Requiem Mass, it is closer to its source material than other Requiems, such as those by Mozart or Berlioz, and could, in fact, be used liturgically if one wished (and could pull it off). It is safe to assume, given his own faith, that Duruflé had the corresponding liturgical action in mind while he wrote his work for concert.

The chant of the final movement, In paradisum, is sung as the body is taken out of the church and led to the cemetery. It is noteworthy from a musicological point of view that, following his friend and mentor Fauré, Duruflé extends his Requiem beyond its normal form that would conclude with the Communion antiphon Lux aeterna and adds two additional movements based on the chants that are sung after the conclusion of Mass: Libera me and In paradisum. But this extension is also theologically significant. Duruflé recognizes that the Church’s prayer for the dead extends beyond the funeral Mass itself and, in reality, never ceases until death shall be no more (cf. Rev. 21:4).

In paradisum deducant te Angeli;

In tuo adventu suscipiant te martyres,

Et perducant te in civitatem sanctam Jerusalem.

Chorus angelorum te suscipiat,

Et cum Lazaro quondam paupere,

Aeternam habeas requiem.

May the angels lead you into paradise;

May the martyrs receive you at your arrival,

And lead you to the holy city Jerusalem.

May the choirs of angels receive you,

And with Lazarus, once poor,

May you have eternal rest.

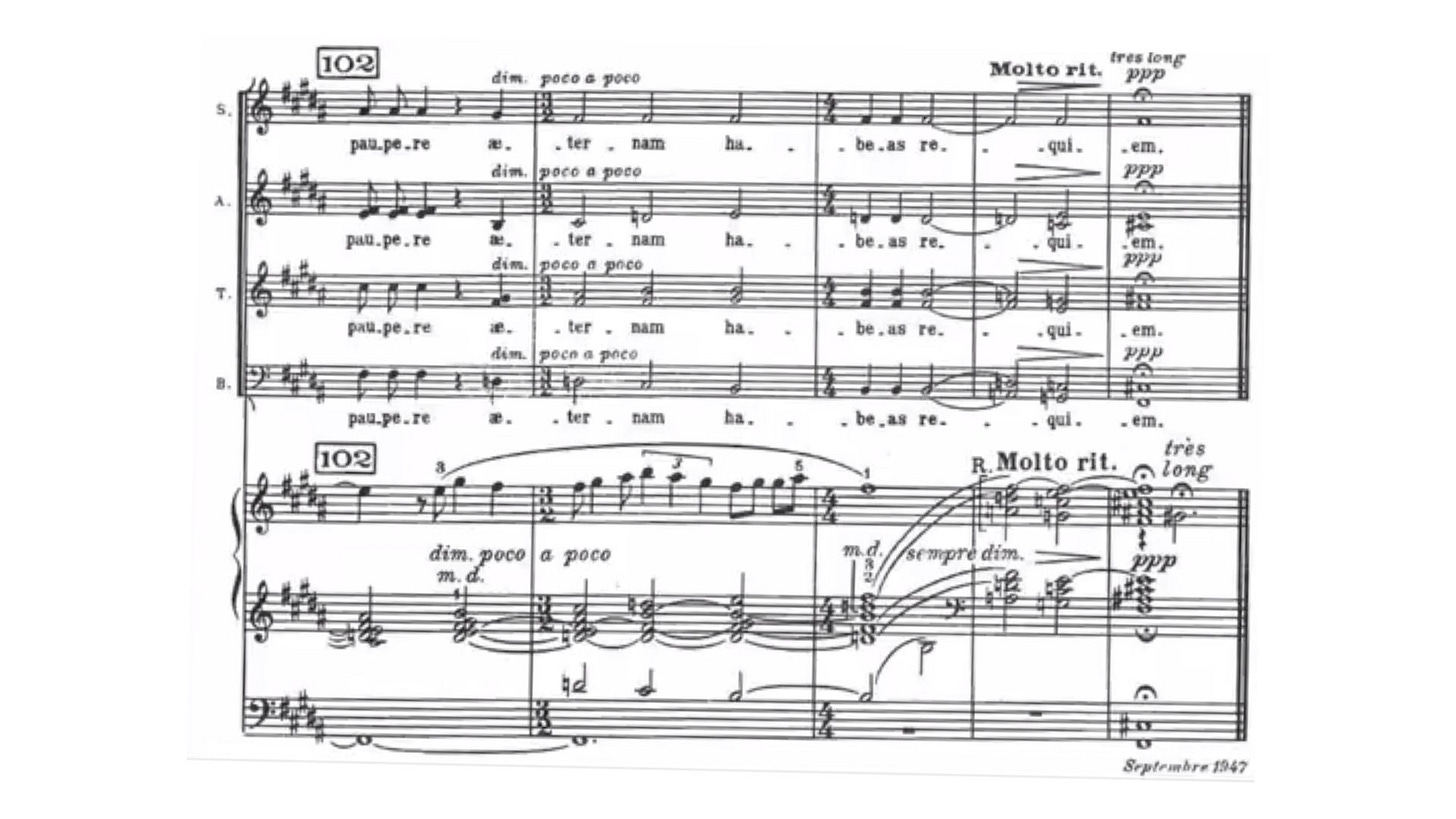

Duruflé’s In paradisum is divided into two sections. In the first, the chant melody sung by a soprano carries the soul to God while the unstable chords beneath make a tonal center difficult to discern, already expressing an air of uncertainty as the movement begins. In the second section, the chant gives way to a full choir of voices delightfully depicting the chorus angelorum that receives the blessed soul into its eternal reward. But then, we arrive quickly to the end of the brief movement and finally to the dominant seventh chord that supports and colors the closing word: requiem. Its harmonic dissonance suggests the rest of which it speaks has not yet been fully attained. The Gregorian antiphon ends on the same note on which it began, making it easy to start the antiphon over to continue the prayer while the body is transferred to the grave. Duruflé seems to be inviting a similar continuation by depriving us of the satisfaction of the music’s completion. The music feels incomplete because our prayer for the dead is incomplete. Our prayer for the soul to reach its requiem must go on.

Duruflé said his Requiem “tends to translate human feelings before their terrifying, unexplainable or consoling destiny.” Here, the human feeling being translated is the uncertainty and lingering dissonance that remains in death’s wake. The happy songs and cheery words that saturate many funerals today tragically overlook the inescapably human feelings that arise when confronted with death that Duruflé, here and in so many places, leans into. The Requiem does not sing of “detachments from earthly worries” but, rather, is sometimes filled with “hope”. What I believe Duruflé is doing at the conclusion of the Requiem is evoking hope – not certainty – in eternal rest. Certainty defies our human feelings of loss and worry in moments of loss. Hope embraces them and follows them through the agony of the cross and to the glory of the resurrection. Countless depictions of Mary weeping at Calvary teach that even the fullest faith in Christ the Redeemer still leaves place for pain and grief.

We have certainty in Christ’s victory over death. We have hope that his victory would be victorious in those who have left this world and in us who remain. What decides the outcome is not the Redeemer’s triumph or his desire to save us, but our ability to accept it. In his desire that we would be saved, he offers, beyond the time allotted us in this life, time in the next for his victory to win us for his kingdom. Our unceasing prayers for the faithful departed carry them, through the mercy of God, through their purification to have eternal rest.

Quoted in “The Duruflé Requiem: A Guide for Interpretation,” Butler University Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection (2000), 4.