Her Sin Is Her Lifelessness

As with each of her albums, the world is too small on Taylor Swift's latest

Maybe five years ago, an argument broke out among some friends about music. Someone made the claim that classical music is really all that is good for us as human beings. We are creatures distinguished by our intellectual powers and classical music engages the intellect in a way that no other musical genre can. Forms of popular music appeal more to our emotions and common sentiment. My friend argued that classical music also works upon the emotions, but in a way that always engages the intellect more than our most base passions. My response to the argument is simple enough: we are creatures who are also distinguished by our capacity for language, and so any musical genre that foregoes the use of human words cannot possibly be all that is good for us as human beings. Human beings are storytellers. We possess a radical self-awareness in our lives that pushes back against the boundaries of space and time. Our self-awareness bestows upon us a remarkable gift for placing our lives within the context of narratives that might include the whole of history or the whole of the cosmos. There are no real limits to the stories that we might tell, or about whom we might tell them.

Most artists and singer-songwriters today do not tell stories through their music. To be fair, most musicians in most musical generations do not tell (or have not told) stories through their music. Popular musicians of most musical genres—rock and roll, punk, disco, heavy metal, electronic, and the everyday pop you hear on the radio—long ago settled for the expression of emotion or experience or of a cause worth fighting for through their art. Most songs you hear on the radio are short, not long enough to tell a story. And most songs you hear on the radio tell you something about the life of the artist who has written the song, but not by way of crafting a narrative. Most songs you hear on the radio and most songs you hear on most albums seek to get at truth through means other than storytelling, which is, of course, a genuine form of artistic expression. But it is a form of artistic expression that leaves to the side something vital about our human capacity for language and self-understanding.

Taylor Swift stands out from most modern artists because of her consistent efforts to tell stories through song. Type in a Google search for ‘Taylor Swift storyteller’ and you will receive ample confirmation that Taylor takes her storytelling seriously: The Storytelling Genius of Taylor Swift’s ‘Evermore,’ Storytelling Lessons Writers Can Learn from Taylor Swift, Follow Taylor Swift’s Creative Process to Improve Business Storytelling Skills, to cite only a few of the top results. The first Taylor Swift single to make the crossover from country to pop radio is entitled Love Story, a narrative about young love that invokes the familiar Romeo-Juliette relationship to capture the impassioned tension of modern teenage love. For over fifteen years now, Taylor has sought to craft songs through the telling of stories, and she has done so regardless of the genre in which she has written her songs; country, pop, dance, indie, the occasional subtle nod toward rock and roll . . . whatever genre Taylor touches become a new sound for the telling of a story.

As a lover of music, Taylor Swift has long fascinated me. Her songs or albums never captured much of my attention during her early years of popular success. But as each Taylor Swift album release became an increasingly more significant cultural event, I began to listen and to learn. There is no mistaking the ambition and the drive of Taylor Swift. For myself, it was reading of her childhood determination to succeed as a musical artist that first told me that Taylor is a musician to be taken seriously. What also became clear to me is that Taylor takes her songwriting seriously. Each album released is an attempt to master some new genre or style of music. And on every album there are the stories told to a culture that has largely forgotten the value of narrative in songwriting. Hearing All Too Well for the first time convinced me that Taylor Swift is not like most other artists in the world of popular music. The lyrical detail of the song is astounding, and affecting. To hear Taylor sing “Here we are again in the middle of the night / We’re dancing round the kitchen in the refrigerator light” is to witness an artist render the utterly mundane into an image of personal beauty that can be shared—expressed—and most musical artists you hear on the radio today are not crafting these kinds of songs.

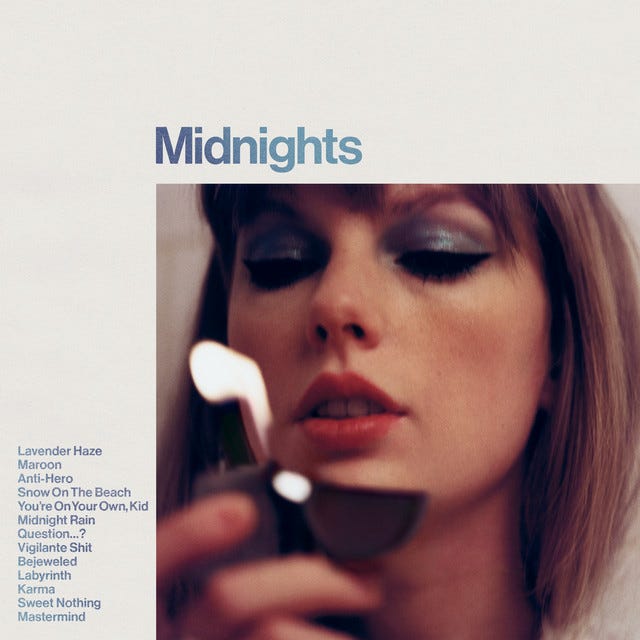

Last Friday, Taylor Swift released her latest album, Midnights. The album is a collection of 13 songs “written in the middle of the night, a journey through terror and sweet dreams,” as Swift has describe the album. Each song is its own story, a reflection upon a sleepless night experienced at some point in Swift’s life. As far as Taylor Swift releases go, Midnights in many ways is her most consistent album. The music is exceptionally well-crafted, and perhaps for the first time on a Swift album not even a casual listener would want to skip a song to move on to something else. The sound of the album—though distinct between its first and second halves—is remarkably cohesive. The songs on the album belong together. And each song is engaging, attractive, and finds a way to hold your attention. To my ears, Midnights sounds like a return to the style of 1989 yet tempered and restrained through the experience of crafting the more recent indie-sounding albums Folklore and Evermore. The album, in a remarkable way, sounds like a sincere reflection on experience: the music is ruminative, deliberate, considered.

The problem with the album are its lyrics—the stories that Swift tells—which is not a thought that you expect to have when listening to a new Taylor Swift album. Playing the album for the first time last Friday, I was surprised by my immediate reaction to Midnights about halfway through: boredom. The stories did not grab me or hold my attention. The narrative arc of the album was of no interest to me. The music captured my attention. The sound of the album attracted me. But what became clear to me was that the music was drawing me into a world about which I do not really care, or find fascinating.

There is a way in which this has always been the case with Taylor Swift albums. The narratives that Swift crafts through song typically feature characters and experiences from the life of a privileged suburban young woman struggling with romance, and I am not a privileged suburban young woman struggling with romance. Sometimes, Swift deviates from the model and writes a song that surprises through its novelty. Soon You’ll Get Better from Lover tells the story of a daughter coming to terms with her mother’s cancer diagnosis; You Need to Calm Down, also from Lover, is a first foray into the world of political activism; The Last Great American Dynasty from Folklore meditates upon the life of socialite and composer Rebekah Harkness, who previously resided in Swift’s mansion on Watch Hill; No Body, No Crime from Evermore is a tale of murder and revenge. These songs are novelties in the storytelling universe of Taylor Swift. The average Taylor Swift song concerns love in all its forms—unrequited, troubled, cherished—told from the perspective of an upper-middle-class young woman living in modern America, which accounts for much of the demographic from which Taylor Swift draws her millions of fans.

For nine albums released over the course of sixteen years, the stories told by Taylor Swift held my attention despite the fact that I am not a member of the demographic she speaks of in her songs. And this is precisely the great strength of storytelling: the capacity for a story to draw a listener into the life of a person he or she does not know and to share the reality of experiences with which the listener has no familiarity. A good storyteller can get a listener to care about any character or event or experience through their craft, and for nearly the whole of her career, Taylor Swift has told the kinds of stories that demand a listener’s attention for the sake of their narrative power (the power of the music helps, as well).

So, what goes wrong with the storytelling on Midnights? Why do the narratives of the album—these thirteen sleepless nights—not capture a listener’s attention and draw them into the life of another person as these stories have always done in the past? Here is my answer: by reflecting through storytelling on thirteen past experiences of sleeplessness, Taylor Swift has exposed the poverty of the world in which she lives. By the term ‘poverty’ I do not mean the realities of homelessness, unemployment, or access to medical care or educational opportunities; stories about those kinds of experiences would likely be interesting. The poverty of Taylor Swift’s world is different. It is the existential poverty of living a privileged life that is—despite its fame—remarkably ordinary and distanced from the experience of, well, anything that would be interesting upon hearing about it for a second time.

The narrative world of Taylor Swift is too small—it always has been—but the songs on Midnights exposes the poverty of Swift’s universe in a way that is distinct from all previous albums. And as far as good storytelling goes, that makes sense to me. A high school girl can tell a story about the drama of her romantic life in a way that holds your attention and draws you in, maybe just for a moment, to a world of which you are not familiar. A young woman in her early 20s can relate something of the experience of the search for real, mature love through a narrative that makes you care, maybe just for a moment, about the realities of a life that is not your own. But to return to those experiences—to reflect upon stories already told for the sake of crafting new stories—is to reveal a poverty in a life that is not interesting. Taylor Swift is a 32 year old with the problems of a high school girl, and there is no quality in songcraft that can redeem that kind of smallness in a narrative worldview. There are only so many times you can dance in the kitchen by the light of a refrigerator before needing to accept that maybe you need to leave the house more often.

Taylor Swift seems to know that something is wrong in her narrative world. The first single released from Midnights, Anti-Hero, admits of a certain poverty in life: I have this thing where I get older, but just never wiser / Midnights become my afternoons. Swift admits that in many ways her life has reached a point of stasis: It’s me / Hi / I’m the problem / It’s me, goes the chorus of Anti-Hero. An album filled with reflections upon the poverty of her narrative world might have been interesting. But despite the candor of Anti-Hero, the rest of Midnights demonstrates a total absence of compelling stories.

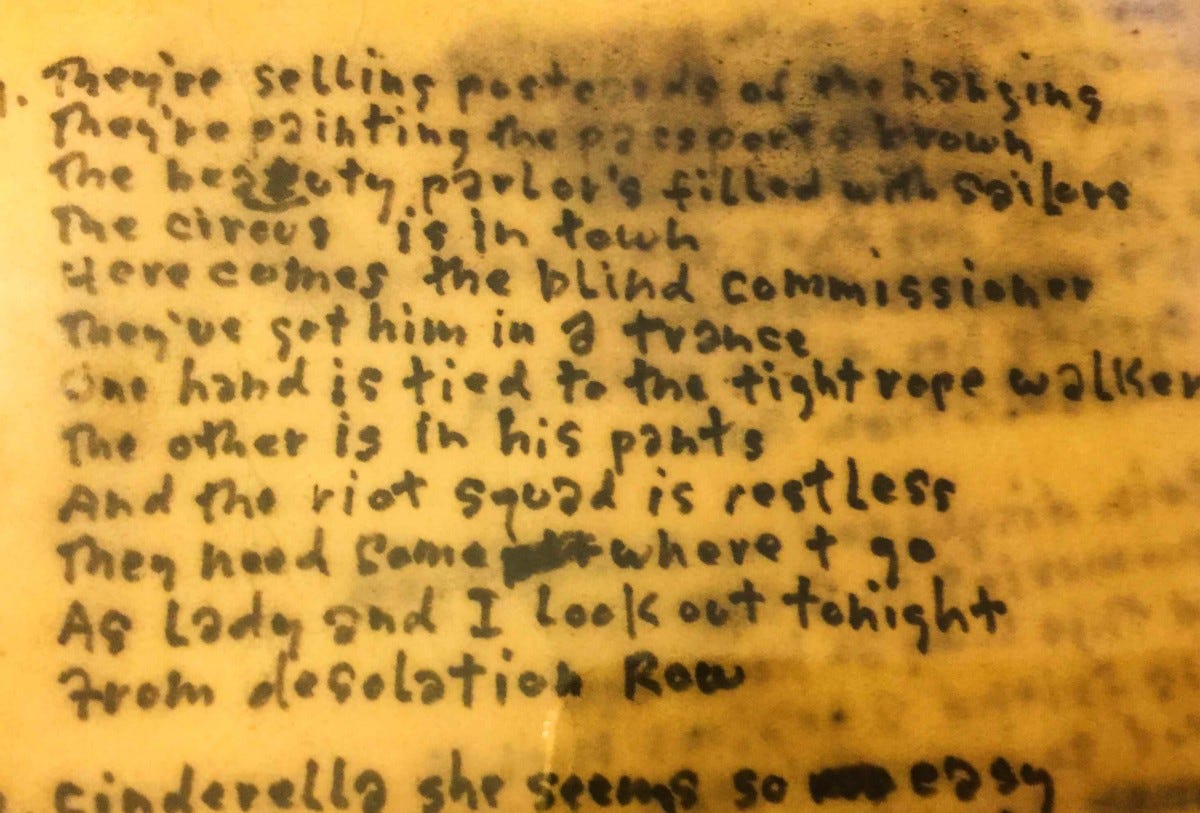

About halfway through listening to Midnights for the first time, my most palpable desire was to listen to a better storyteller—an experience I have never had while listening to a Taylor Swift album. I thought of Bruce Springsteen and his use of baptismal imagery on The River to capture that struggle of family life in industrial America or of the way that the narrative of the resurrection is used to frame the desperation of the central character in Atlantic City. I thought of Janis Joplin’s rendition of Kris Kristofferson’s Me and Bobby McGee, and her remarkable talent for telling the story of a romance against the backdrop of a culture-in-transition with a chorus of freedom is just another word for nothing left to lose.1 I thought of Bob Dylan and the miracle of a song like Desolation Row with its depiction of life in 1960s New York City told through the re-presentation of figures from scripture and world history.

What marks the difference between the narratives of songwriters from generations past and Taylor Swift? A first difference concerns content: Taylor Swift writes songs about what she knows—what she experiences—and the knowledge and experiences that are revealed through her songs belong to a world that is very small. Mostly, Taylor describes the problems and tensions of suburban privilege and those stories might hold the interest of a listener for a moment but not for a career. The struggle in Taylor’s songs is real, it just isn’t all that novel or important. A second difference concerns form or style: the songs of Taylor Swift lack completely the kind of imagery you find in the narratives of songwriters from generations past; not only is the world of Taylor Swift very small, but the universe of language which she uses to describe her world is equally impoverished and limited. The consequence is a genuine absence of transcendence in Taylor’s songs regarding what is true or good or beautiful. There is no way to move beyond the boundaries of Taylor Swift’s narrative world into a world that is larger and more expansive. There is no greater context in Taylor’s songs, and rarely is there greater meaning. Instead, there are only stories about the love life of a privileged young woman whose experiences are not a part of—or even gesture toward—realities beyond the boundaries of her own experience.

These differences between the narratives of songwriters of generations past and Taylor Swift have always existed, but Midnights is the album that makes these differences clear. My response to the experience of listening to the album was to open up Spotify and load Dylan’s Desolation Row; I wanted to listen to a story that captured by my attention and drew me into a world that fascinates me. And there amidst the figures described by Dylan in his song I found an image of the life of Taylor Swift:

Ophelia, she's 'neath the window

For her I feel so afraid

On her twenty-second birthday

She already is an old maid

To her, death is quite romantic

She wears an iron vest

Her profession's her religion

Her sin is her lifelessness

And though her eyes are fixed upon

Noah's great rainbow

She spends her time peeking

Into Desolation Row.

A life that is immune to the struggles of most human lives but that takes interest in those lives like a voyeur. A myopic life driven by career ambition, lacking any talk of God or transcendent notions of the true or the good or the beautiful. A life distanced from the kinds of experiences that render a person vulnerable to the world—to reality—and result in a narrative world that is genuinely universal. The sin of Taylor Swift is her lifelessness. A 32 year old ought to have something more to say about the world, about life, about the realities of common human experience. But most of what Taylor knows—most of the stories that Taylor tells—reveal that Taylor is not a part of a world that is larger than herself.

What struck me most about Midnights is the impoverished secularity of the songs. These songs are secular insofar as there is no mention of God or the transcendent or of the eternal goods for which human beings strive. And these songs are impoverished insofar as there is no greater cultural context captured through narrative language. There is no baptismal imagery, no language of the resurrection, no talk of Napoleon or Einstein or T.S. Elliot, no talk of freedom or injustice. Taylor Swift tells stories about herself—or about people like her—and beyond those limited experiences there is nothing more to say. Midnights reveals the narrative impulse of a teenager who lives within the life of an adult, for whom ‘maturation’ in storytelling means a more frequent use of profanity and a more constant discussion of sex.

Songwriters of generations past had better stories to tell, and they told them better.

This essay was edited from its original publication to acknowledge Kris Kristofferson, rather than Janis Joplin, as the writer of Me and Bobby McGee.

Thoughtful reflections.