Holy Desire: Theology of the Body and the Eucharist

Thoughts on creation, bodiliness, and Christian experience | Edward Herrera

The following essay was originally given as a presentation to young adults on August 1st, 2022 for the Café Catholica Series of the Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston. The presentation has been lightly edited for publication on Ecclesia Christi Baltimore.

March 2020. In March of 2020 my family, like so many families across the country, was preparing for my oldest son Max’s First Communion. He was supposed to receive First Communion in May of that year, but you know the rest of the story. Ultimately, he received later in the summer at an outdoor Mass at our parish—not exactly the way we planned it. The pandemic was challenging for many people for many reasons. And for us, with the closure of our parish and Max’s inability to receive his First Communion, we felt acutely a desire—a hunger—for Christ in the Eucharist. I don't want to overly dramatize this reality but what I would say is that the Eucharist and the sacraments are part of our DNA as Catholics. The Eucharist and the sacraments are the lifeblood of the Christian faith. As the Church teaches, the Eucharist is “the source and summit of our faith.”1

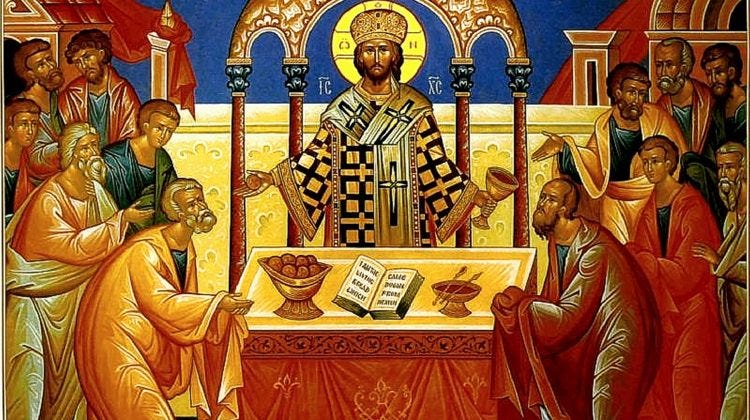

But there is nothing new here. The 20th Century theologian Henri de Lubac noted that today our understanding is that the Church makes the Eucharist but in the early history of the Church, the understanding was that the Eucharist makes the Church.2 As St. John Paul II said, the Church draws her life from the Eucharist.3 For me, perhaps the most striking example of this comes at the turn of the 3rd century, during the reign of the Diocletian—one of the worst experiences of Christian persecution in the early Church. At that time, there was a Bishop named Emeritus who was caught celebrating the sacrifice of the Mass. The consequence of participating in the Mass during those years would have been death. So, Bishop Emeritus was caught celebrating the sacrifice of the Mass and was brought to the Roman authorities and there he was asked Why, knowing that you would be put to death for this sort of action, would you do this? Why would you celebrate the Mass if it meant death? And his response was: Sine dominico non possumus.4 This simple Latin phrase can be translated: Without Sunday we are not able. For us today, the grammar doesn’t make much sense. For our ears it sounds like an incomplete sentence. Without Sunday we are not able to do what? The point that Bishop Emeritus makes is fundamental: he makes a point that goes to the heart of our being. This Bishop of the early Church was speaking one of the most profound and simple truths: without Sunday we are not able because, indeed, what we do on Sunday makes us who we are. Without Sunday we are not able to be. If we don’t have Sunday, if we don’t have the Eucharist, we have nothing.5

St. Peter offers a similar profession. In John 6 we read the Bread of Life Discourse. As you may recall, the Bread of Life Discourse is John’s ‘institution’ of the Eucharist, since in John’s account Jesus washes the feet of the apostles during the Last Supper. In John 6, Jesus very descriptively tells the crowd to eat his body, using language that would be better translated to ‘gnaw’ on his body, lest there be confusion with Christ’s meaning. When you read those verses of John, Jesus makes his meaning very clear. And when many who hear these words then desert Christ, he turns to the Apostles and asks: Will you too leave? Rarely does Peter get it right, but in that moment, he speaks a truth from the depths of his being. Peter says: Lord, to whom should we go? You have the Words of eternal life. Peter had been in the physical presence of the Lord. He had been with the Lord and from that encounter, Peter was able to speak in a manner that surpassed human understanding. Peter was in the presence of the Bridegroom and knew that there was nothing else but the Lord. Peter encountered the physical Lord and in that encounter was able to offer an astoundingly free and faith-filled response to Jesus. The fact that Peter had been with Jesus and spent time with Jesus—Peter knew that this man, Jesus, fulfilled the longings of his heart. And while I can parse this out in some deep metaphysical terms, the point really is that Peter, a simple fisherman, knew that through the words Jesus spoke and who Jesus is makes him the only one who can truly satisfy.

But why? Why is this Eucharistic desire so firmly rooted in our heart? Deep within us we have a desire for a relationship with the God of the universe and we desire that relationship in a physical way. To understand such a physical yearning, we need to return to the beginning—the beginning of scripture and to the root of human origins. St. John Paul II took a similar approach. When writing on the meaning of the body, sex, and marriage, John Paul returns to creation. And in doing so, St. John Paul II was really following Christ, who when asked about marriage and divorce also turned to the beginning. There is a method used by Christ and by St. John Paul II that will help us to understand our physical desire for the Eucharist.

Now for a truth we know well: God created everything that exists. The whole world, the whole universe all came into existence through God’s Word. To use a technical theological phrase: we believe in creation ex nihilo, a world created out of nothing. It took me a very long time to wrap my head around that concept and it is still very much a mystery. For me, when I think of creation out of nothing, my head always goes to creation out of something because that is how I create. For example, about a month ago, I created what I think is a pretty amazing Ninja obstacle course for my kids but I did it with pressure treated wood, which came from trees (and chemicals), which came from the earth. So, for me, when I think of creation out of nothing, I am still framing it in the context of something. It is like I think that God had a big box of nothing—you know as though nothing is really something—and then God creates the world. But the point is that there was absolutely nothing and then there was something—nothing and then something.

Another truth we know well: God is good. And a good God would only create a world—a universe, a cosmos—that is good. God doesn’t do the best he can with what he has to work with; God deals in perfection; God deals in goodness. There was nothing and then God creates something and that something is good. And not only is it good, but what God created reflects the truth, the goodness, and the beauty that is God. Every speck of creation, down to the smallest atom was loved into existence and imbued with meaning by a God who made in precisely as it is.

St. Paul writes in his letter to the Romans: Creation is groaning in labor pains, and we, groan within ourselves waiting to be made known. All the created world is groaning waiting to be made known. Creation, or put it another way—reality—is revealing something to us. Creation is revealing something to us about ourselves and something about God. In fact, creation is, in a particular way, hardwired to reveal God to us. As we hear in the prologue of John’s Gospel, in the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things came to be through him, and without him nothing came to be. Creation is marked with the sign of the Creator and is made through the Son, the logos—the Word of God. Creation was made in such a way that it magnifies the glory of the Lord. We can even say that creation is sacramental because it bears the mark of God. This might seem strange to us since when we hear the word ‘sacrament’ we think of the seven sacraments—Baptism, Eucharist, Confirmation, Reconciliation, Marriage, Holy Orders and Anointing of the Sick. Yet, the Catechism explains that sacraments are visible signs of God’s grace and what is grace besides God’s love? The sacraments very much are visible signs of God’s love. And these visible signs of God’s love are written in the very fabric of creation.

And I want to take this a step further and ask a pointed question: if we in our lives have had an encounter with the Eucharistic Lord that has changed us, why should we discount any other aspect of the Lord’s created order?

When I enjoy a beautiful sunset, or go on a trail run with my kids, or when my 6-month-old daughter, Teresa, smiles back at me, I know something of the beauty and goodness and love of God. This doesn’t mean we slip into some sort of pantheism where god is in everything and in nothing; but, God is truly present in His creation. As St. Augustine said, God is more in me than I am in myself, so it is no wonder that the Catechism says, God speaks to man through the visible creation. Then we see that the seven sacraments of the Church are privileged experiences of God’s grace ordained by Jesus Christ. Far from medieval inventions of the Church, these seven sacraments speak to the deepest longings of our heart for communion with God, which is desire that we have had in us from the beginning.

The seven sacraments are the height of a redeemed creation, the sacraments are the true calling of the created world. One might even say, for example, that water was made for Baptism. It is for this reason that a bishop in the earliest parts of the Church could say unto death without Sunday we are not able. The physical desire for the presence of the Lord is written on our hearts from the beginning. This is the profound truth that Peter spoke, probably not fully understanding it himself. God made us for communion with him and we experience something of that communion physically in this world which speaks of God at every turn and he is truly present to us, body, blood, soul and divinity in the Eucharist. The Eucharist is the full realization of what creation was made for—to reveal Christ to the world and draw us to the heart of the Father.

The truth of creation, which sheds light on our Eucharistic hunger—our hunger for the Lord—also speaks of the decisive truth about our lives. Creation tells us something of our deepest desires. The Catechism teaches that: God speaks to man through the visible creation.6 Too often in today’s world, there is an attempt to silence the language of the physical world. But the Christian is called to hear the voice of God speaking through creation and to invite others to do the same. The created order is far from meaningless: it is infinitely meaningful. I think this point bears some reflection because it is something that has been cast aside even for so many Catholics, so I will say it again. The physical world—creation—speaks to us. We live in an age, however, in which many Catholics have reached a point at which they perceive the physical world—even our own bodies—as an obstacle to our freedom. But those kinds of thoughts for the deeper truth that creation—including our created bodies—are revelatory.

And this is what we’re talking about when we use the language of the Theology of the Body. The Theology of the Body really means that our body has a meaning beyond itself. Our bodies are sacramental, which is to say they reveal something of God, which is affirmed in the book of Genesis. We are made in God’s image and likeness. And if we were made in the image and likeness of God, then we were made by Love and for Love.

Too often the Church is accused of physicalism or biologism, which is the claim that Catholics see morality as reduced to the physical world and our bodies. The most common example of this accusation is that the Church teaches that the goodness of a marriage is reduced to matters of sex: a good marriage is one in which the sexual act brings a couple into closer unity and is open to the possibility of bringing about new life. One might think that this teaching seems obvious. But there are many in the world today who see this understanding of marriage as a reduction of the person and morality to the physical; to the biological. I don’t believe the teaching of the Church here is a reduction at all. I would argue that the Church considers the full meaning of the body: for the Church, the body is understood in and through the whole of creation. God speaks to us through creation. And as people of faith—who receive the grace of revelation—we have received an image of creation and of the human person that is beautiful and that reminds us of the love of God.

I do concede this point: much of our contemporary understanding of the body and desire—out there in the world, sometimes even in the Church—is severely truncated. In fact, the internal logic of many contemporary cultures presents a real disintegration of the person as the Church understands the human person. To look at my desires completely as detached from my body or from the physical world fails to account for how human persons experience the world. To see ourselves as spirits trapped in bodies corresponds neither to experience nor to what is revealed to us through faith. To understand the fullness of my desire, my desires must always be understood in light the physical world and from the perspective of my experience. The Church—contrary to what many think about her teaching—offers a robust understanding of the human person, a vision of the human person that accounts for our desires, our emotions, our physicality, and our spirit.

To take the sacramentality of creation seriously is to move beyond mere wonder in our engagement with the stuff of the cosmos. To wonder—to respond to our experiences of the created order with curiosity and desire to know that which is unknown—is good. But for the Christian, to behold the beauty of a sunset ought to result in something more than wonder. The experience of beauty should draw us into a deeper relationship with the One who fashioned this world from nothing. The experience of beauty should invite us to a new way of life. Far from eliciting a cold indifference toward the world, an encounter with beauty compels us from the within because beauty speaks to the purpose of our lives. Beauty speaks to our innate and lasting desires for God.

If we return to the Gospel of John and Peter’s response to Jesus, we know that Peter had a physical encounter with Jesus Christ and that physical encounter very much changed Peter. However, to say that there was only a physical encounter with Jesus is to dramatically reduce what took place. And I think that is the case for us in all our relationships—whether those be relationships with a friend, a fiancé, a spouse, a sibling or a parent. We develop relationships through the physical world but to say there is no spiritual dimension to those relationships reduces the reality of our love. When we meet someone, when we get to know them, we are really getting to know that person; and that person has much more depth than the physical matter that we encounter. They are much richer than a physical body; in fact, it is only through their body that we come to know who they are within.

Perhaps the most concrete and obvious example of the sacramental reality of creation is found in Christian marriage and our experience of love. Love was the reality that captivated Pope Saint John Paul II. He dedicated himself to understanding the human person in terms of love, which is why it should come as no surprise that when he began his pontificate, John Paul II declared to the universal Church that: man’s (or woman’s) life is incomprehensible to himself if he does not experience love.7 But the love that John Paul II speaks of is an embodied love. Man and woman were made—created—for one another. As it says in the book of Genesis, for this reason, a husband should leave his father and mother and cling to his wife and the two shall become one flesh. And while we know that this one-flesh union is physical, I don't think that many would argue marriage is only a physical reality. We know that there exists a sexual complementarity between man and woman that engages more of the human person than mere flesh. Christian marriage—like every aspect of Christian experience—must be understood through and transformed by the light of Christ. To behold a relationship between husband and wife is to behold an image of the relationship between Christ and his Church. Engagement and experience with the physical draw a person into a deeper relationship with the One who fashioned the world from nothing.

An orthodox thinker, a contemporary of John Paul II, named Paul Evdokimov once wrote: We speak of a certain anamnesis (remembrance), a mysterious reminiscence found in each true love. Every man carries within himself his own Eve, and lives in the expectation of her possible Parousia (second coming).8 Our physical desires and experiences must be seen through the light of Christ and our human longing for God. The method here in no way diminishes or dismisses the created order but is instead the fulfillment of the created order. There are questions here regarding the sacramentality of creation and the good of human relationships that challenge our spiritual lives: What part of God’s creation calls me into deeper relationship with the Creator? What do I desire? How can Christ help me to better integrate my spiritual longings with my physical desires? Where do I need to incorporate the Church’s wisdom into my desires?

My hope is that these reflections serve as an invitation to awaken our experiences and desires through an encounter with the created world. The life of encounter with creation builds faith and sustains hope since the created world is groaning, waiting to be made known—waiting to reveal God to us.

For us Catholics, I think the bishops have it right: we need a Eucharistic Revival. But I mean that in the deepest sense of the word: a re-vival, a returning to life. We can’t be superficial about God’s presence in our lives. We must enter into the depths of our desires, which are only for the Lord. To recover a devotion to the Eucharist is to recover an understanding of a created order: an extending out of the life of the loving God who has loved us into existence. To encounter the presence of Christ is the sacrament is to receive new horizons for our lives. To live in the presence of Christ gives meaning and understanding to everything. And when we fail to purify our desires, we become distracted from the One who satisfies.

When I think back to March of 2020 and how often—at least for me—the Eucharist and sacraments were taken for granted, I am haunted by Pope Francis’ words in an empty St. Peter’s Square: The tempest lays bare all our prepackaged ideas and forgetfulness of what nourishes . . . people’s souls; all those attempts that anesthetize us with ways of thinking and acting that supposedly “save”. . . prove incapable of putting us in touch with our roots.9

Edward Herrera serves as the Director of the Institute for Evangelization of the Archdiocese of Baltimore.

CCC §1324.

Henri de Lubac, The Splendor of the Church.

John Paul II, Ecclesia De Eucharistia. §1.

Benedict XVI, General Audience (September 12, 2007).

Here I should note that the work of David L. Schindler, particularly his article in the Fall 2007 Issue of Communio entitled: "Liberalism and the Memory of God: The Religious Sense in America" was the first place I became aware of the phrase and reading of “Sine dominico non possumus.” Further, anything interesting that I have written is credit to the great faculty at the John Paul II Institute in DC.

CCC §341.

John Paul II. Redemptor Hominis. §10.

Paul Evdokimov, The Sacrament of Love.

Pope Francis, Urbi et Orbi Blessing (March 27, 2020).