Human Wounds, Divine Remedy: On the Winters of Our Own Experience

A Christian Reflection on Bon Iver's Emma

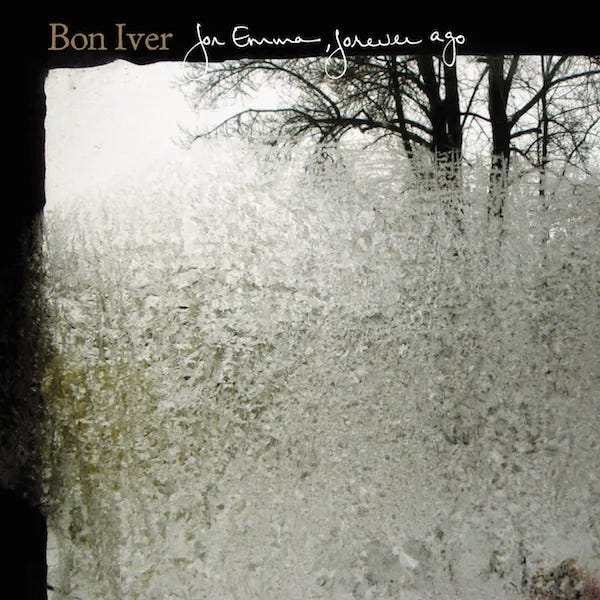

Fifteen years ago, singer-songwriter Justin Vernon emerged from a winter’s convalescence spent in his father’s hunting cabin in western Wisconsin with an album of self-recorded music that he would soon release as the first of his new band, Bon Iver.1

Vernon may or may not have written For Emma with religious motives in mind, and such discussion admittedly runs the risk of over-spiritualization. But he nevertheless speaks to a fundamental dimension of the human experience and so touches upon the point of departure for the whole Christian dispensation: a fallen human nature that is riddled with interior and exterior dimensions of discord. A Christian listener cannot resist the invitation to see the work as at least an expression of natural religiosity. And perhaps as something more: as a song form open to divine revelation; at times even reminding of the sacred reflection upon revelation that we call theology. Where along that continuum For Emma, Forever Ago falls is open for debate. But what cannot be denied is the presence of religious experience in Vernon’s music. Our task is to uncover what For Emma, Forever Ago allows us to see of the human condition; where the door is left open for divine grace; and how we might recognize the contours of the face of the incarnate love of God in the person of Jesus Christ.

The essay that follows will (1) summarize the story of Emma with its insight into the human condition and then (2) connect that insight to the Christian experience of conversion (3) in the hope of discovering within Emma the presence of Christ.

I

For Emma, Forever Ago (2007) expresses the deep tensions of a conflicted heart that loves and hates the past. The recording history of the album is a legend itself: Vernon retreated to the wilderness after breaking up with his band and his girlfriend to recover from mononucleosis and to distance himself from a run of bad life choices and bad song writing. The life left behind in Raleigh is made present through the allegorical ‘Emma’ of the album. The identity of Emma Vernon clarified in an interview: “Emma isn’t a person. Emma is a place that you get stuck in. Emma’s a pain that you can’t erase.”2 Vernon sings of Emma as if she had broken his heart—and indeed she has—but For Emma is more than a breakup album with a cultivated aesthetic. It is a 37-minute plunge into a conflict felt viscerally within every human heart; the kind of conflict that warrants discussion at a spiritual and theological level.

There are many ways to make sense of the meaning of the songs on For Emma, Forever Ago. But for the Christian listener the most spiritual narrative arc is to see the album as descriptive of an inclination—sometimes an attraction—toward something of the past from which one cannot escape but with which one must comes to terms. An album composed in retrospect, For Emma is always Forever Ago. Vernon looks from his present winter of introspective isolation toward a past romance with Emma, hoping to learn what hold she still has upon him and to what degree she will be with him in the future.

Looking back in Flume, Vernon sees himself and his pursuit of Emma as sympathetic to the mythical Icarus’ flight with “gluey feathers” that melted when he flew too close to the sun. Justin Vernon’s flight toward Emma had been just as tragic. With a view to the future, Vernon looks to the sky, to the vast array of possibility before him, and is drawn not the sun (the source of its own light) but to the moon (a surface that only reflects the light of another)—an image to which Vernon will return at the end of the album when he has gained greater perspective. But even here on the first track is Vernon aware of the effect his pursuit of Emma has upon all future possibilities. He is too wounded to trust himself with his love and so he circles around the open sky in fear of again being hurt: “Lapping lakes like leery loons / Leaving rope burns, reddish rouge”. A wounded Vernon continues to fly but Emma remains the brightest and most attractive element above: “Sky is womb, and she’s the moon.”

Lump Sum then draws us into the cabin with Vernon as he begins to process that woundedness. He realizes that the wound runs deep and has spread like cancer throughout his being: “My mile could not / Pump the plumb / In my ardor ‘til my ardor trumped / Every inner inertia, lump sum / All at once / Rushing from the sump pump.” He realizes—not without a tinge of skepticism—that he cannot escape treating the wound at its core (“Or so the story goes”). The future is unknown for Vernon. In what state of health Vernon comes out on the other side of a cold Wisconsin winter remains a mystery to him: “Balance we won’t know / We will see when it gets warm.”

The most well known song of the album is Skinny Love, a song that elucidates the inner tension of Vernon’s heart as he begins to war within himself regarding Emma past and present. The song opens with a hopeless plea for her love “to just last the year” despite the “sink of blood and crushed veneer.” Emma has left him and Vernon wishes to put out of his mind his desire to stay with her (“Pour a little salt, we were never here”). He bargains their future relationship on the condition that Emma must change: “And I told you to be patient / I’ll be holding all the tickets / And you’ll be owing all the fines.” By the end of the second chorus however Vernon realizes he has bargained too much. Emma has not changed at all but Vernon has: “And now all your love is wasted / And who the hell was I? / And I’m breaking at the britches / And the end of all your lines.” Wounded by these disastrous attempts at love, Vernon concludes with piercing questions about his future and Emma’s: “Who will love you? / Who will fight? / Who will fall far behind?” These questions carry us into the remainder of the album.

In Act I of The Wolves we find Vernon separated from and yet connected to Emma (“Solace my game, it stars you”). He appears to want nothing more than for Emma to experience his own pain so that he might relish in her destruction (“With the wild wolves around you / In the morning I’ll call you”). Act II stages a different scene as Vernon agonizes over what this separation has cost him (“What might have been lost?”) even as the faint echo of conscience still tries to push her off (“Don’t bother me”). Between both acts Vernon is deeply conflicted and must somehow resolve that conflict lest he continue to be of two hearts.

Blindsided, like Lump Sum before it, returns us to winter at the cabin and introduces us to the important image of snow. With the words “contrasting the snow,” Vernon compares the pure whiteness of snow with the agony of his own heart that he does not fully understand but that he knows has blindsided him. As he follows the “Taut line / Down to the shoreline” he comes to “The end of a blood line” (perhaps the end of his bloody affair) to the recognition that “The moon is a cold light.” Emma’s cold light has left him freezing, and yet something warm within him makes “My feet melt the snow” and this, too, blindsides him as he starts to feel a pull toward someone other than Emma.

Creature Fear returns to the vista of possibility in Flume’s imagery of the womb of the sky and as it does Vernon has gained a greater ability to speak about his fear of choosing any possibility that is not Emma: “So many foreign worlds, so relatively f***** / So ready for us, so ready for us / The creature fear.” What he fears is that any love aside from Emma will leave him just as wounded (“So did he foil his own? / Is he ready to reform?”). If he has not reformed himself, in loving someone else will he not continue to love Emma under another name?

The instrumental track Team represents Vernon’s grappling with his fear in solitude—away from the listener—that leads him to the conclusions that he voices in the album’s title track For Emma. Through his introspection Vernon arrives at the clarity to see that there is both attractive good and repulsive ugliness in Emma (“With all your lies / You’re still very lovable”) and this admission opens the door for him to embrace a new, unknown life without her. As he saw her once as the moon (reflecting a light not its own) he now sees her as the “sunny snow” on which he only sees “death”. The beautiful irony here is that Vernon can see the sun (the source of its own light) reflected upon the deathly snow and this vision sets his sights to “Seek the light” down “So many foreign roads” and leave Emma behind, “forever ago”.

With Re: Stacks Vernon faces the future (“Everything that happens is from now on”) although the first movement along his uncharted journey is painfully through darkness. He turns to the escapism of alcohol to evade his problems but they remain the ‘stacks’ on his back that weigh him down. Each line of the chorus carefully changes words that evidence Vernon’s gradual realization that he himself must deal with them: “On your back with the racks as the stacks of your load” then becomes “In the back with the racks and the stacks are your load” and finally “In the back with the racks and you’re unstacking your load.” The stacks on his back are not simply going to go away. He recognizes that they are his load and that he must be an active agent in unstacking them if he is to find the light/lightness he seeks. Two haunting images accompany the latter half of the song – “the fountain in the front yard [that] is rusted out” and the “black crow sitting across from me / His wiry legs are crossed / And he’s dangling my keys, he even fakes a toss” – that add punch to the final stanza: “This is not the sound of a new man.” Indeed it is not.

In coming to the album’s final track Wisconsin,3 Vernon has returned home to brace winter in the cabin. As he arrives he knows that Emma is already inside the cabin and cries, “Oh, God, don’t leave me here, I will freeze ‘til the end” as “Winter is coming and you’re stuck here / Oh, and so is she.” Skinny Love’s question returns—“Who will you love?”—and now he adds as he sees the snow that reminds him of Emma, “What’s love when you’ve hurt?” At the close of the album he realizes that these questions will stay with him wherever he goes beyond the cabin (“‘Cause every place I go, I take another place with me”) and that whatever and whoever he loves, he will love with “love’s critique”—with the part of him that will always still love Emma.

II

The being-at-war with oneself that characterizes For Emma is classically understood in the Christian tradition as a residual effect of the fall that can be mitigated but not entirely extricated from a person’s being-in-the-world. ‘Concupiscence’ is the theological term inherited from Augustine for this phenomenon but the best description of this internal war was stated earlier by Paul writing to the Romans: “I do not understand my own actions. For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate,” (7:15); and again, “For I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want is what I do” (7:19). While by revealed knowledge we are shown the cause of (and a fortiori the remedy to) this conflict, one need not be a Christian or believe in anything at all to know the reality Paul articulates. That is why Vernon’s treatment of concupiscence in For Emma appeals to a wide audience spanning the creedal horizon. Everyone knows what he is talking about; and the path that Vernon charts through Emma is the path from the life of slavery to sin to the life of freedom in grace that the Christian must trod by grappling with concupiscence in whatever form it takes.

If we take Emma as an allegory for concupiscence—as a painful state in life from which we desire escape—we see in Vernon’s internal conflict throughout the album something of our own individual battles with the human tendency toward evil.

First, there is the bottoming out that precedes the search for a better life. The Gospel parable of the Prodigal Son (cf. Lk. 15:11-32) is an easy corollary to Vernon’s experience of being left in the filth of his own choices in Flume and Skinny Love. No conversion or change in life happens without the realization that the road one has been going down leads only to a dead end; and that realization requires honesty and humility. Vernon articulates both realizations in Flume: “I wear my garment so it shows / Now you know.” Pain exacerbates that realization and intensifies the need to escape from shameful realities.

The first step in conversion is to turn away from the object of one’s wayward love. Lump Sum describes what Vernon has “sold… for a venture home / To vanish on the blow.” There cannot be any movement away from a love that is not accompanied with the intention to make a clean break from the chains that bind us. For as Christ says, “No one can serve two masters; for he will either hate one and love the other, or he will be devoted to one and despise the other” (Matt. 6:24). Our fractured hearts will attempt to serve both masters but the heart that God desires is undivided (cf. Ps. 86:11). And any conversion worthy of the name requires cooperation with grace. The grace of conversion moves a person toward a unification of the heart through a rejection and despising of sin in all its deceptive allure.

The witness that Vernon gives on the album reveals that our own concupiscent love for the allegorical Emmas of our own lives infect us at a deeper level than we might at first think. It is not simply this sin or that vice to which we are attracted but rather that we are pulled at the level of being toward that which is disordered and in conflict with God’s will. Recall in Lump Sum Vernon’s realization that “Every inner inertia, lump sum / All at once / Rushing from the sump pump” comes to the surface as he grapples with his own particular instantiation of Emma. If we take conversion seriously we likewise see how there is more within us that needs reordering than simply whatever caused us to bottom out in the first place.

And here we arrive at the crossroads of Christian conversion. The remedy needed for our waywardness so far exceeds our capacity for self-treatment that there are only four options about where to go from here: (1) to try as best as one might to make whatever progress toward freedom that is (naturally) possible; (2) to regress and seek comfort in whatever pleasure Emma and her sisters may offer and accept the pain of regression as better than the unknown pain of a life in “So many foreign worlds” (Creature Fear); (3) to attempt to evade both the quest for freedom and the pain of regression by turning to anything that numbs oneself to reality (Vernon’s chosen path at the beginning of Re: Stacks) even to the thought of suicide; or (4) to seek assistance outside oneself at a level above the merely human to save oneself from that which is fundamentally human: the pull toward evil. The Christian faith teaches that only the final option—the offer and reception of grace—is worth pursuing, and yet the pull of concupiscence is so strong that only a saint relies exclusively on divine assistance free from occasions of relapse and recidivism. That is why the pain and tension of For Emma, Forever Ago is viscerally felt by those who have pursued the Christian path of conversion.

On the album, Justin Vernon shows no perceptible signs of looking to grace for healing. But there are two moments on For Emma consistent with the path of Christian conversion that are worth drawing out. First, in the image of seeing “death on a sunny snow” there is the admixture of good and evil that underlies his pull toward Emma. Emma is “still very lovable” and thus there is real goodness in her to which Vernon is attracted. Thomas Aquinas teaches that the will has the good for its object and so whatever the will desires it wants insofar as it is good.4 Seeing whatever is good within what is evil (à la “death on a sunny snow”) allows one to turn more deeply into that good and pursue it in its higher and unadulterated form. The parallel verse “You’re still very lovable” admits that good maturely while moving away from her for “all your lies”.

Second, the album ends with the admission that his love of Emma will stay with him wherever he goes and in whoever else he chooses to love (“Who will you love? What’s love when you’ve hurt?”). This kind of sober self-knowledge is vital to the lifelong fight against concupiscence; the Emmas of a past life will always stay with us; the pull toward sin will always remain; we will always stand in need of the healing that can only come by humble reception of the love of God given in the gift of divine grace.

III

This essay suggested at the beginning that we might consider Justin Vernon as a kind of natural or common theologian. That claim is only true for an artist who gestures toward the subject of all theology: the God-man Jesus Christ. So, there is a question here: does For Emma, Forever Ago reflect the face of Christ? That question is answered through Vernon’s revelation that “Emma is not a person.” Emma—so understood as a conflicted state of being-in-the-world—cannot be a person for what Emma represents is the lack of a good that ought to be present in a person’s life. Metaphysically, Emma can only ‘be’ what she is not. Yet behind whatever absence of good that is perceptible in her is seen the true and perfect good, who is in fact a person, the person of Jesus Christ. The Christ who reveals to us in human flesh and through human experience—even and perhaps especially through our experience of sin—all that is true, good, beautiful, and worthy of our love. Christ himself is the light and all things reflect light insofar as they reflect him. Pursuing Christ in all things is the pursuit of the highest love that orders our hearts to love what is passing in this world only for the sake of what is eternal. The ordering of the passing to the eternal—the visible to the invisible—that kind of order alone will keep the Emmas of our own lives from consuming us.

For Emma reveals to us the depths of our brokenness and our need for divine grace. And so heard through the filter of Christian faith the album helps us to see the face of the Christ who comes to us, lifts us from our wayward loves, unites our hearts, and leads us through our winters into the warmth of his light.

Bon Iver is derived from the French bon hiver meaning “good winter”.

Sam Sweeney, “Justin Vernon is Going Home,” The New Yorker (November 26, 2015).

Not part of the original album, Wisconsin was later released as an iTunes exclusive.

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae I-II q. 8, a. 1.

I think the late Fr. Raymond Brown would be very pleased with this beautifully written essay, especially because of the depth of understanding it reveals.