One Thought I Have About the Paris Olympics Opening Ceremony

The meaning of secular culture is becoming clearer

I

Imagine you are an average high school student: you are pretty focused on your life and your problems, you struggle with self-confidence, and you find yourself in a social environment in which everyone is talking about everyone and everything all of the time—a culture of casual gossip, judgment, and criticism. The environment in which you find yourself combines with your self-focus and self-doubt to dispose you toward suspicion and paranoia. Each time you enter a locker room and catch people laughing, or go to the library and hear people whispering, you conclude that they are laughing at you or whispering about you.

But then one day you tell yourself that enough is enough, and you start asking people why they are laughing at you, or why they are whispering about you. And what you discover is that no one laughed at you, and no one whispered about you; there was another cause for the laughter, another cause for the whispering. What you discover, to your devastation, is that no one in the locker room even noticed you were there, and no one in the library ever took the time to realize you are a student at the school.

In other words, what you are left facing is the reality of your own irrelevance: no one cares enough about you to mock you, or pays enough attention to you to make your life the subject of gossip. You find that your social irrelevance is actually more painful than living as an object of scorn or ridicule; at least people who get judged and mocked get noticed.

II

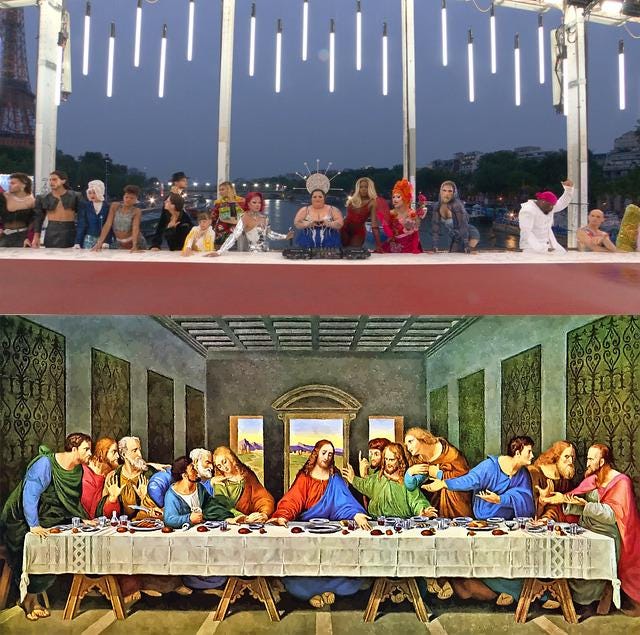

There have been many comments made about the image of people dressed in drag gathered around a table during the Opening Ceremony of the 2024 Paris Olympic Games. Many people made an immediate connection to Leonardo da Vinci’s famous painting of The Last Supper, and identified the scene as a mockery of Christian faith. For the past few days, social media feeds and Christian blog sites have been consumed with talk about the deliberate, offensive choice of those who organized the Paris Opening Ceremony to insult a world religion; surely, the organizers of these events would not mock Islam in such a way. Bishops in many countries have also criticized the organizers of the Paris Games, and just about everyone who offers regular commentary on matters of religion and culture has staked out a position for or against this new 21st century ‘version’ of the last supper.1

I agree with those who object to the mockery of Christian faith: if the choreographed scene from the Paris Olympics is a direct reference to da Vinci’s The Last Supper, then the image is offensive, an insult to the reality of Christ and to the devotion of those who follow him.

III

The choreographer who designed the controversial set-piece for the Opening Ceremony gave yesterday a formal statement about the intentions behind the design. Thomas Jolly said the design had nothing to do with Christianity at all, explaining that:

The idea was to do a big pagan party linked to the gods of Olympus. You'll never find in my work any desire to mock or denigrate anyone. I wanted a ceremony that brings people together, that reconciles, but also a ceremony that affirms our Republican values of liberty, equality and fraternity.2

There is no way to know if the explanation that Jolly gave is a calculated response to a media nightmare, or is a sincere account of the intentions of those who planned the Opening Ceremony. For what it is worth, to me the claim to referencing pagan feasts and Greek gods make sense: the Olympic games find their origin in Greek culture, and the celebration of ancient pagan beliefs is exactly the kind of event you would expect from a non-Christian worldview. No one can say for sure what happened, but I am not convinced the set design was a deliberate mockery of the last supper. In fact, go ahead and search on Google for images of ‘Greek gods banquet,’ and you will find plenty of old-to-ancient works of art depicting pagan feasts that resemble what we see in da Vinci’s The Last Supper. I am no art historian, but perhaps a painter working during an age defined by its return to classical antiquity might just have drawn some inspiration from older images of pagan gods feasting; images of gods feasting around a table are certainly easy enough to find from the Renaissance period.

IV

The possibility that the Christian faith was mocked during Friday night’s Opening Ceremony is not particularly interesting to me; if it happened, nothing more would have occured than what Christ warns us about again and again in the Gospels. God will not be mocked, sure, but those who follow Christ ought to expect derision and criticism from the world. If Friday night was an intentional insult, then Christians might need to start better managing their expectations about how the world will treat us. Why expect a reality different from the one Christ describes for us?

More interesting to me is the possibility that choreographers and designers were not thinking of Christianity at all during their planning of the Opening Ceremony. Is it possible? Might it be only coincidence that an image of 21st century persons dressed in drag feasting around a table closely resembles da Vinci’s famous depiction of the Apostles gathered with Christ in the Upper Room on the eve of his passion and death? How might it be possible for these set designers and choreographers to not be thinking about Christianity at all during the planning of Friday night’s Opening Ceremony given the image that was presented?

The philosopher Charles Taylor talks about our loss of shared references of meaning in the modern (and secular) world. He uses art as an example of his claim, and I am going to give you several quotes through which Taylor lays out this argument:

The change I want to talk about here goes back to the end of the eighteenth century and is related to the shift from an understanding of art as mimesis to one that stresses creation . . . It concerns what one might call the languages of art, that is, the publicly available reference points that, say, poets and painters can draw on . . . painting could long draw on the publicly understood subject of divine and secular history, events, and personages that had heightened meaning, as it were, built into them, like the Madonna and Child or the oath of the Horatii.

But for a couple of centuries now we have been living in a world in which these points of reference no longer hold for us.

We could describe the change in this way: where formerly poetic language could rely on certain publicly available orders of meaning, it now has to consist in a language of articulated sensibility.3

The change that Taylor describes is cultural. He talks about an age of modern secularism in which images of meaning are no longer universal: no longer can an artist depend upon the fact that everyone within a culture knows the meaning of an image of the cross, for example, or of a snake broken into fragments on a flag warning ‘Join or Die.’

Taylor talks about modern secular culture as one defined by fragmentation:

[Fragmentation means] a people increasingly less capable of forming a common purpose and carrying it out. Fragmentation arises when people come to see themselves more and more atomistically, otherwise put, as less and less bound to their fellow citizens in common projects and allegiances. They may indeed feel linked in common projects with some others, but these come more to be partial groupings rather than the whole society: for instance, a local community, an ethnic minority, the adherents of some religion or ideology, the promoters of some special interest.4

The secular age in which we live is fragmented: we define ourselves first as individuals (atomistically) who then make a personal choice to care about belonging to groups of one kind or another; maybe an ethnic group or a religious group or a group formed around a political ideology. The consequence of fragmentation is that there no longer exists a shared universal grammar of meaning within a culture; you know the language of meaning that defines life in your social group, but how much do you pay attention to the languages of meaning within groups with which you do not identify?

Maybe an example from history will help make Taylor’s claim clearer. In the decades following the death and resurrection of Christ, an image of the cross assumed a meaning for Christ-followers that did not resonate for those belonging to other social groups in the Roman Empire. To most within that fragmented culture, an image of the cross symbolized a horrific form of public condemnation, not a victory over death or a source of hope for eternal life. A non-Christ follower who witnessed Christian veneration of the cross would have been confronted with a question of meaning: the image would have meant nothing good to him or her, so what is the Christ-follower doing?. The fact that centuries later an image of the cross possessed a universal meaning in much of the West is a testament to the extent to which Christianity formed a universal culture.

But the culture of a unified Christian West is now broken and fragmented. We live as individuals who identify with groups, and our languages of meaning are no longer universal. I know the grammar of meaning particular to my social groupings, but do not consider myself familiar with the languages of meaning belonging to other groups; drop me into a rally fighting for Catalonian freedom and I do not expect to know much about what anyone is talking about.

V

So, what happened during the Opening Ceremony of the Paris Olympic Games? If you ask many 21st century Christ-followers, you will be told that a group of secular post-modern atheists advocating for new forms of moral disorder created a set design meant to intentionally insult Christ and those who follow him. The image of persons in drag gathered around a banquet table is an intentional re-presentation of da Vinci’s The Last Supper aimed at those who hold onto traditional moral and religious values. In other words, to many Christians what happened on Friday night is the latest volley fired in our 21st century culture wars.

Maybe there is another account of what happened. Maybe a group of secular post-modern atheists who do not identify with Christianity, no nothing of our history or beliefs, do not care much about us or think about us—and who most certainly do not share our language of cultural meaning—created a set design that conforms to about 230 years of misguided French enthusiasms about liberty, fraternity, and equality for the opening ceremony of an international event that most people still know has something to do with ancient Greece; and so we ended up with people dressed in ancient drag gathered around a banquet table.

Here is what I mean: we who follow Christ witness a scene like the one created for the Opening Ceremony of the Olympic Games and immediately conclude that secular post-modern atheists are attacking us. But maybe those secular post-modern atheists do not know anything about us because they do not care about us, take no notice of us except for when political exigency requires a fight, and absolutely do not share our language of meaning. Maybe many of us who follow Christ are like the high school student who concludes that everyone in the locker room is laughing at them, and everyone in the library is whispering about them, who has yet to learn the vital but devastating fact of their own irrelevancy.

People need to care about you to know your language of meaning, and then to use your own language to mock you. Maybe the choreographers of the Opening Ceremony for the 2024 Olympic Games are intimately familiar with 15th-century Christian iconography. Or maybe they don’t care enough about us to know anything at all.

VI

Let’s say that Charles Taylor is right AND that Thomas Jolly is telling the truth about French national intentions. What is a Christ-follower to do about a secular world that no longer finds Christianity relevant enough to know anything about Christian faith? What do you do when the hard truth is that no one cares enough about you to notice you?

There are many ways to answer those questions, but for the sake of a short response, consider the life of that high school student in the grip of social suspicion and paranoia. What ought that student to do? Here are 3 simple answers.

(1) Get over yourself, get out of your house, and go love people; drop your focus on yourself and your problems, and go find people who need care and live a life of charity.

(2) Find some real confidence, real faith, in who you are and what you believe. Your suspicion and paranoia is a product of your own doubt, so get to work on becoming a real believer in who you are and what matters to you.

(3) If you find it hard to exist in a culture of casual gossip, judgment, and criticism, then maybe you should make sure you do not belong to that culture yourself.

Those are just a few possible responses to the possible fact of 21st century Christian irrelevancy. But there is no doubt that the universal Christian culture that once existed was built on a foundation of real faith and real charity. Anyone who wants that kind of culture to exist again needs to find some conviction, drop the personal doubt, get out of the house, and go find people who need care and live a life of charity. Live that kind of life—and stop gossiping and judging—and you might be surprised by the kind of culture we can build.

https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/news/258431/words-cannot-describe-it-bishop-cozzens-responds-to-heinous-last-supper-mockery-at-olympics#:~:text=%E2%80%9CJesus%20experienced%20his%20passion%20anew,this%20through%20prayer%20and%20fasting.

https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20240728-paris-sorry-for-any-offence-over-opening-olympic-ceremony

Charles Taylor, The Ethics of Authenticity, pp. 82-84.

Charles Taylor, The Ethics of Authenticity, pp. 112-113.

This is awesome, thank you Fr. Brendan. I will share this with family and friends.