I’d like to preach just on today’s Second Reading from the Letter of Paul to Philemon.

Clocking in at a mere 25 verses, it is one of the shortest books in the Bible. While brief, one New Testament scholar has said that if the Letter to Philemon was the only document we had from the early Church, we would still know a great deal about Christianity and its revolutionary message.1 And if we take a closer look at this letter, I think we’d find that the message Philemon transmits is no less revolutionary for us today.

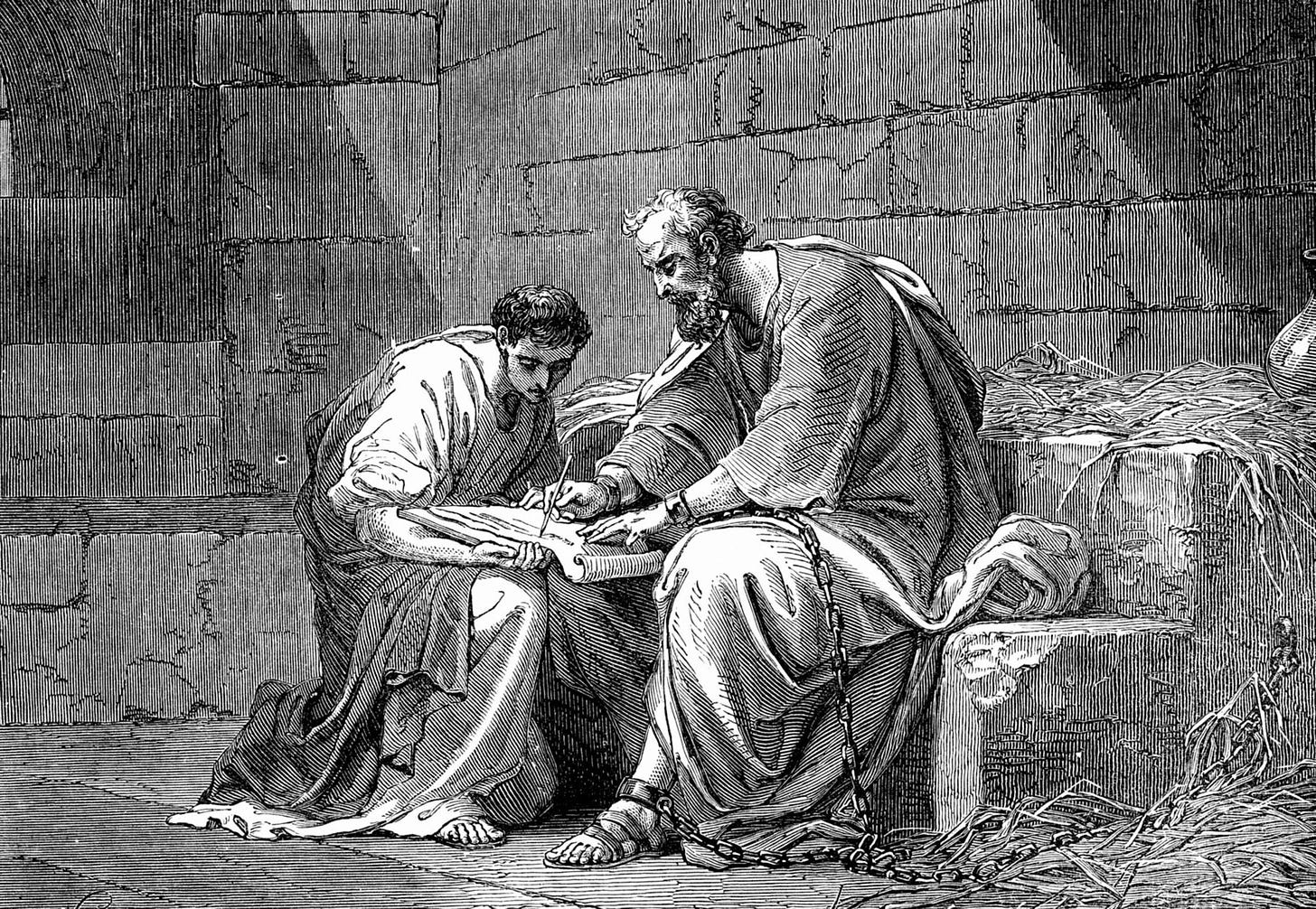

Paul’s letter is addressed to Philemon, a man who lived in the town of Colossae in Asia Minor or modern-day Turkey. Philemon, like everyone else, owns slaves; and one of his slaves, a slave called Onesimus, has run away and perhaps committed theft in the process. Onesimus flees from Colossae and journeys three days west to the coastal city of Ephesus. And in Ephesus, somehow or another, Onesimus finds Paul, who is in prison. Now, Paul is in a difficult position. Paul is good friends with Philemon, Onesimus’ master; and according to the social conventions of the pagan world, he ought to send the delinquent slave back to his friend in chains to be properly reprimanded, perhaps even killed. What complicates Paul’s response is that Paul is not pagan but Christian and – more to the point – since Onesimus has met Paul, he himself has become Christian too. And Paul, better than anyone, knows that Christianity and slavery simply cannot coexist. So, what is Paul to do? Paul decides to send Onesimus back to Philemon. But he does not send him empty handed. Paul sends with him a letter; and it is this letter to Philemon that we have to this day in the New Testament.

Paul writes to give advice about what Philemon should do with Onesimus. Now, we should remember that slavery was a pillar of the economy in the ancient world. People may have known to varying degrees that slavery was wrong; but we all know what it is to believe something is wrong and not change our behavior. Since people’s livelihoods depended on slaves, when slaves got out of line, disciplining them was a serious matter. And there was no shortage of advice about how to administer punishment. In one case, the Roman senator Pliny counseled his friend to receive back a prodigal slave with open arms – that is, until he messed up again: You can always be angry again if he deserves it, and will have more excuse if you were once placated.2

But the letter that Paul writes to Philemon gives vastly different counsel. And we can account for the difference by the fact that Paul and Philemon and now Onesimus are all Christians; and as Christians they are called to live at a higher level than the pagans around them. Paul, therefore, makes his case, with great tact, not for Onesimus’ punishment but rather for his freedom.

After the opening pleasantries, Paul gets to the point: I, Paul… appeal to you for my child, Onesimus, whose father I have become in my imprisonment (10). In the Greco-Roman world, it was possible (even if rare) for the father of a household to receive their slaves into his family by legal adoption. Paul clearly had that in mind when he wrote elsewhere that the Spirit of God makes us sons of God; and that receiving the Spirit of God, you did not receive the spirit of slavery to fall back into fear, but you have received the spirit of sonship.3 Because Paul has been the conduit through which the Spirit has made Onesimus an adopted son of God, Paul can legitimately claim a kind of spiritual fatherhood over Onesimus that he now uses as leverage over Philemon to barter for the slave’s freedom.

Paul continues: I am sending him back to you, sending my very heart (12). Paul is in prison and cannot go to be with his friend Philemon. Paul, therefore, identifies himself with Onesimus so that Philemon will have to receive his slave back into his household as he would receive Paul himself. And this means that he must consider him no longer a slave, but more than a slave… a beloved brother… both in the flesh and in the Lord (17). And so, Paul concludes, if you consider me your partner, receive him as you would receive me. If he has wronged you at all, or owes you anything, charge that to my account (18).

Paul pleads for Onesimus’ freedom by identifying the slave with himself. And in this, Paul has truly heeded his own words to have the mind the Christ.4 In his other letters, Paul teaches that Christ died for us, while we were still sinners,5 took our sins upon himself, and canceled the bond which stood against us with its legal demands.6 As Paul sees it, if that is what Christ has done for him, then that is what he also must do. And as a prisoner for Christ Jesus (1) Paul leans on the weight of the Gospel to secure the freedom Christ has won for Onesimus, a prisoner of Philemon.

We lack any certainty about where Onesimus ended up. In the year 110, however, a letter by Ignatius of Antioch names the Bishop of Ephesus as Onesimus.7 Although we can’t be sure it is the same person, it would be quite remarkable if this runaway slave became the bishop of the city in which he met Paul and through Paul found his freedom in Christ. Even more, that the Christians in that city could accept a bishop with a checkered past would speak volumes to just how revolutionary the Gospel was that Paul preached.

Whether that was Onesimus’ fate or not, in any case, we do know that the Gospel has toppled the legitimacy of any economy built on the backs of slaves. There is simply no way to take the Gospel seriously and hold people in chains. We also know that history (particularly Christian history) has taken time to recognize that inherent contradiction and resolve the disparity between doctrine and praxis. Our own country ‘conceived in liberty’ upon nominally Christian ideals built itself into an empire by the cracks of whips. And we should not be deceived to think there remains no further disparity on that front to resolve.

Slavery exists today; and it exists in a variety of forms: the physical slavery of those compelled to forced labor; the social slavery of those oppressed by unjust laws; the psychological slavery of those dominated by those in authority over them; and the slavery we exert over those in our lives every day that we keep under our thumb. For however much Christ has set us free, pride will always threaten to tighten the chains in one way or another.

What Paul’s Letter to Philemon offers in response is a vision, a way of seeing the other, that is profoundly and distinctly Christian. This vision sees freedom where the world sees chains; inherent dignity where the world sees economic gain; brothers and sisters where the world sees resources it only flippantly calls human. What distinguishes this vision is our alliance, like Paul’s, to the Onesimus in our midst: to identify ourselves with them, to make our heart one with theirs, so that when the world receives back its slaves it will receive us along with them. What the Church’s social mission demands is that when the poor are trampled the Church is trampled along with them. The Church calls this unity solidarity; and it is grounded in Christ who always stands in solidarity with us. Paul possessed that vision – a vision that defied the vision of the world around him – and his letter challenges us to make it our own, that our corner of the world would know the freedom the Gospel alone brings.

May Paul, Philemon, Onesimus, and all the saints who stood their ground with the slaves in their midst pray for us that we may stand in solidarity with the slaves in ours.

Preached at the Cathedral of Mary Our Queen on September 3 & 4, 2022.

N.T. Wright, “N.T. Wright on Philemon: ‘Think Christianly’” (YouTube).

Pliny, Epistle 9.21, quoted in N.T. Wright and Michael F. Bird, The New Testament in Its World (London: SPCK, 2019), 466.

Rom. 8:14, 15.

Cf. Phil. 2:5.

Rom. 5:8.

Col. 2:14.

Cf. Ignatius of Antioch, Epistle to the Ephesians, ch. 1.