Our Most Important Conversations Are Going Nowhere

Some Thoughts on Wittgenstein and Using Language

My infancy did not go away (for where would it go?). It was simply no longer present; and I was no longer an infant who could not speak, but now a chattering boy. I remember this, and I have since observed how I learned to speak. My elders did not teach me words by rote, as they taught me my letters afterward. But I myself, when I was unable to communicate all I wished to say to whomever I wished by means of whimperings and grunts and various gestures of my limbs (which I used to reinforce my demands), I myself repeated the sounds already stored in my memory by the mind which thou, O my God, hadst given me. When they called some thing by name and pointed it out while they spoke, I saw it and realized that the thing they wished to indicate was called by the name they then uttered. And what they meant was made plain by the gestures of their bodies, by a kind of natural language, common to all nations, which expresses itself through changes of countenance, glances of the eye, gestures and intonations which indicate a disposition and attitude—either to seek or to possess, to reject or to avoid. So it was that by frequently hearing words, in different phrases, I gradually identified the objects which the words stood for and, having formed my mouth to repeat these signs, I was thereby able to express my will. Thus I exchanged with those about me the verbal signs by which we express our wishes and advanced deeper into the stormy fellowship of human life, depending all the while upon the authority of my parents and the behest of my elders.

—St. Augustine, Confessions (Book 1, Chapter 8)

Those words from St. Augustine open the Philosophical Investigations of Ludwig Wittgenstein, published posthumously in 1953. Most anyone familiar with my intellectual interests knows me for my love for the works of Hans Urs von Balthasar, Jean Danielou, St. Augustine and other Fathers of the Church, and, perhaps somewhat begrudgingly, the structured framework of reality crafted by St. Thomas Aquinas that no honest Catholic intellectual can escape entirely (nor should want to). But my first great love of the mind was Wittgenstein. Maybe (almost probably . . . sorry, Martin Heidegger) the most important philosopher of the 20th century, the way that Wittgenstein went about blending the study of logic and language and metaphysics and mysticism captivated me as an undergraduate. His philosophy still captivates me.

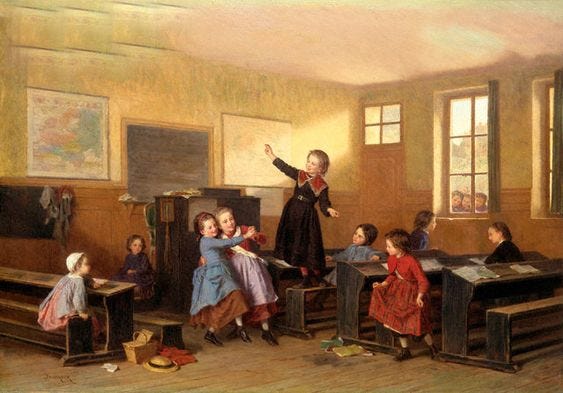

Last night, I lamented to a friend that for the sake of doing well in seminary, I needed to put my love for Wittgenstein to the side for several years. But last week I picked up off the shelf the wonderful biography of Wittgenstein written by Ray Monk, himself a student Wittgenstein’s philosophy of mathematics. The biography is excellent. Born into the moral/political decay of the Habsburg Empire in the late 19th century to a family of great wealth, the life of Ludwig Wittgenstein is a study of the search for integrity and meaning in life. A genius training under the tutelage of Bertrand Russell at Cambridge University in the early 1910s, Wittgenstein abandoned academia for the horrors of the First World War. He found God during the War, and was decorated several times for his valor, serving for four years before spending a year in a prisoner-of-war camp in Italy. During the war, somehow, Wittgenstein managed to compose his first great work of philosophy, the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. After the war, Wittgenstein gave away his inherited fortune. He spent several years teaching elementary school in poor villages outside of Vienna. Wittgenstein, it seems, discerned a call to the priesthood around this time but considered himself unworthy of the call—to his mind, he still lacked the integrity he most deeply desired, and for which he first went to Cambridge and then to the First World War. He didn’t think conversion possible for himself, and so, eventually, he made his way back to England. After years of thinking he had no more to contribute to philosophy, Wittgenstein experienced an intense period of personal, spiritual pain in the 1930s that caused him to question some of his earlier philosophical conclusions. He spent the remainder of his life (Wittgenstein died in 1950) working out a revised theory of logic and language and metaphysics and mysticism that we now possess in the Philosophical Investigations.

There is much that I want to say about Wittgenstein, and maybe I will say more, later. For now, let me share some thoughts about how Wittgenstein can help us understand a problem that frustrates most of us at least some of the time: the seeming misuse of words in conversations about important truths. Here is an example. Some weeks ago, I attended a meeting of pastors and parish leaders in Baltimore City about how we can best evangelize as a local Church. After listening to several people speak about evangelization, I raised my hand (there is no escaping years of Catholic education) and made an objection: no one in the room agrees on what we mean by the word ‘evangelization.’ Some were using the word and talking about faith formation; others were using the word and talking about ecumenical dialogue; still some others were using the word and talking about social justice initiatives. We cannot have a conversation about evangelization, I said, unless there is common agreement on what we mean by the word.

My frustration is not limited to the word ‘evangelization.’ No one in society agrees any longer on what we mean by the words ‘life’ and ‘dignity’ and ‘justice’ and ‘good’ and ‘true’ and ‘beautiful.’ Select a reality that matters, that really counts for something, and you will find disagreement about what certain words mean. How is this possible? Do not words represent defined, settled realities? When we use the word ‘dog,’ we know we are talking about four-legged creatures that shed hair, mimic love for us, and beg for food scraps. There is no confusion there. I could use the Spanish word for ‘dog’ in a conversation with you— ‘perro’ —and if I explained to you that ‘perro’ is the word in Spanish that represents those four-legged creatures who shed hair, mimic love for us, and beg for food scraps, we could carry on using the word ‘perro’ for as long as we would like. We can use any word we want to mean ‘dog’ as long as when we use the word we are pointing toward those four-legged creatures laying on the cold floor with a tail sharply thumping the ground whenever we approach to show affection. Words point toward realities that exist in the world. To know the meaning of a word is to know the thing out there in the world that the word represents.

The theory of language we are describing depends upon what Wittgenstein calls ‘ostensive definition.’ And here is the theory of language learning that St. Augustine describes in his Confessions. The meaning of our words is given ostensively, that is to say, by way of a gesture. Words are signs that point toward realities in the external world. As long as there is agreement on the word-sign and the reality it represents, there ought to be no ambiguity in language. Whenever there is ambiguity in language, it must be a consequence of either: (1) not agreeing on the word-sign, or (2) not agreeing that the thing represented in language really is what it is. So, going back to my experience at a City pastors meeting, the ambiguity in our conversation was a consequence of either: (1) a failure for everyone to use the word ‘evangelization’ in our conversation, or (2) a failure for everyone to agree on what the word ‘evangelization’ points toward out there in the world. The first (1) possibility was not our problem. Everyone in the room used the word ‘evangelization.’ The second (2) possibility, I don’t think, was our problem either. If I had quoted the USCCB and told everyone that "evangelizing means bringing the Good News of Jesus into every human situation and seeking to convert individuals and society by the divine power of the Gospel itself,” I think everyone in the room would have agreed with the definition. There would have been common agreement that the word ‘evangelization’ points toward, gestures toward, means: bringing the Good News of Jesus into every human situation and seeking to convert individuals and society by the divine power of the Gospel itself. And yet, we could have gone for ages talking past one another in conversation. How does this happen?

The contribution that Wittgenstein makes to our understanding of human language is to bring us beyond a theory of language based on ostensive definition. The meaning of a word is not given by pointing toward a thing out there in the world but is given in the use of the word. The correlation of a word-sign to a thing in the world is insufficient for understanding the meaning of a word. Consider the following, says Wittgenstein:

Imagine a picture representing a boxer in a particular fighting stance. Well, this picture can be used to tell someone how he should stand, should hold himself; or how he should not hold himself; or how a particular man did stand in such-and-such a place; and so on.

Several people could agree that the term ‘boxing stance’ means—point toward, gestures toward—the given picture of a boxer standing in the ring, gloves up, bracing for impact. But there is more meaning to the term ‘boxing stance’ than what is given by way of ostensive definition. Is it a good stance or a bad stance? A stance that no boxer would ever use or a stance that one famous boxer used for the whole of a career? You could imagine several people having talking past one another in a conversation for ages about boxing stances and boxing, everyone using the same words, and everyone pointing toward the same image, but each using the term ‘boxing stance’ with a distinct connotation or accent. Language and word-meaning is subtle in exactly this way.

Wittgenstein uses the term ‘language-game’ to describe the reality that the meaning of a word is given by the use of a word. Imagine two people playing checkers. Each uses the word ‘king,’ and neither has any problem going about playing the game. Each player knows that by the word ‘king’ there is no gesture toward George III nor Henry V but rather toward a piece on the game board in a particular position of strength. The meaning of the word ‘king’ is given in its use. Two people playing the same game and agreeing upon the same rules of the game speak to one another with no ambiguity in language. Freedom from ambiguity in language comes from people playing the same language-game. Ambiguity in language reveals that people are playing different games, which means that people are living different kinds of lives. Wittgenstein explains:

But how many kinds of sentence are there? Say assertion, question and command? — There are countless kinds; countless different kinds of use of all the things we call “signs”, “words”, “sentences”. And this diversity is not something fixed, given once for all; but new types of language, new language-games, as we may say, come into existence, and others become obsolete and get forgotten. (We can get a rough picture of this from the changes in mathematics.) The word “language-game” is used here to emphasize the fact that the speaking of language is part of an activity, or of a form of life. Consider the variety of language-games in the following examples, and in others:

Giving orders, and acting on them —

Describing an object by its appearance, or by its measurements —

Constructing an object from a description (a drawing) —

Reporting an event —

Speculating about the event —

Forming and testing a hypothesis —

Presenting the results of an experiment in tables and diagrams —

Making up a story; and reading one —

Acting in a play —

Singing rounds —

Guessing riddles —

Cracking a joke; telling one —

Solving a problem in applied arithmetic —

Translating from one language into another —

Requesting, thanking, cursing, greeting, praying.

It is interesting to compare the diversity of the tools of language and of the ways they are used, the diversity of kinds of word and sentence, with what logicians have said about the structure of language (PI, no. 23).

Language is a rich and complex tapestry of meaning. The implication of Wittgenstein’s language-game theory is that ambiguity in language is expressive of something deeper: an ambiguity in ‘form of life.’ What is his meaning? Only that people who agree to play a particular language-game (people who share a particular form of life) necessarily agree to use certain words in certain ways at certain times and with certain meanings. Consider an easy example: Catholics and Protestants each use the word ‘church’ but because Catholics and Protestants play different language-games (live different forms of life) each use the term ‘church’ differently. And yet both Catholics and Protestants can use the term ‘church’ meaningfully, and with much precision in conversation. Similarly, a group of Catholics belonging to one parish who come together to plan an event can use the expression ‘the church’ without anyone drawing the conclusion that a parish bingo night will soon be held at St. Peter’s in Rome. The language-game is the same.

What is the problem with which Wittgenstein can help us? Well, many of our conversations about truths that matter will remain unhelpful so long as we believe that the meaning of our words is shared and universal within a culture that shares a common language. Maybe, in a distant past, the language-game of culture was much more universal than it is now (though I have my doubts about that). Maybe, in 15th century France, all French-speaking persons played the same language-game and used words like ‘life’ and ‘justice’ and ‘dignity’ in the same way. But in our culture today, English-speakers do not use words like ‘life’ and ‘justice’ and ‘dignity’ in the same way. We talk past ourselves in conversation, discussing matters of politics and morals and religion, each using the same words but most using them in our own way. We aren’t playing the same language-game, and we do not share a common form of life.

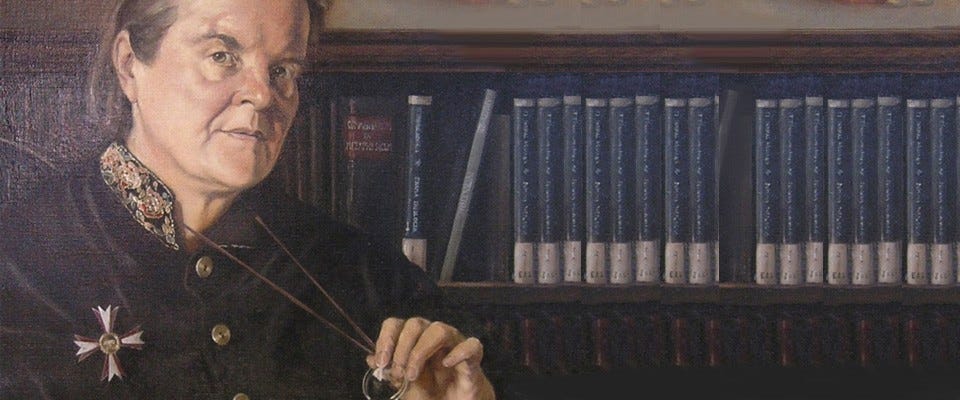

For these reasons, Elizabeth Anscombe—a student of Wittgenstein in the middle of the 20th century and a deeply convicted Roman Catholic—published an essay entitled Modern Moral Philosophy in 1958 calling for us to stop having conversations about morality in contemporary philosophical discourse. Why would a convicted Roman Catholic make such a claim? Is it not crucial for us to fight for truth and beauty and goodness? Well, Anscombe says in the essay that we are only making our problems in society worse by talking past ourselves in conversation. We are not using our words in the same way, but everyone uses the terms of moral vocabulary with meaning. The problem, says Anscombe, is that we no longer live within the Christian culture that gave the words of our moral vocabulary their meaning. We are not playing the same language-game, and we do not share a common form of life.

Anscombe explains that moral terms like ‘is’ and ‘ought’ and ‘sin’ and ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ enjoyed a certain moral-ethical-legal meaning within a Christian culture. But now our common Christian culture belongs to the past, and yet we keep using our inherited moral vocabulary. She explains that:

To have a law conception of ethics is to hold that what is needed for conformity with the virtues failure in which is the mark of being bad qua man (and not merely, say, qua craftsman or logician)—that what is needed for this, is required by divine law. Naturally it is not possible to have such a conception unless you believe in God as a law-giver; like Jews, Stoics, and Christians. But if such a conception is dominant for many centuries, and then is given up, it is a natural result that the concepts of “obligation,” of being bound or required as by a law, should remain though they had lost their root; and if the word “ought” has become invested in certain contexts with the sense of “obligation,” it too will remain to be spoken with a special emphasis and a special feeling in these contexts.

It is as if the notion “criminal” were to remain when criminal law and criminal courts had been abolished and forgotten.

The language-game, the form of life, of Christendom is a thing of the past, and so our modern understanding of obligation and the moral life cannot exist as it once did. I remember watching, for years, the battles in our culture war about who can and cannot get married, combatants on all sides invoking the language of ‘rights’ and ‘love’ and ‘dignity’ and thinking to myself: “Anscombe and Wittgenstein were right . . . no one uses these words in the same way and yet everyone uses these words with meaning and precision, so we’re all talking past one another and becoming more entrenched in our respective positions without knowing it.”

I share these thoughts about language-games and forms of life because, well, Wittgenstein is on my mind this week. And my reading about his life made me recall some of what I love the most about the insights that Wittgenstein gives us about logic and language and metaphysics and mysticism. But there is also the simple fact that, if Wittgenstein is right about human language, well, we aren’t going to convince anyone of much of anything unless they are playing our language-game, sharing in our form of life. We can shout words at one another and gesture towards objects out in the world as much as we like, and we can have as many conversations as we like about what is true and good and beautiful, but there is a good chance that all of our gesticulations and word use will only get us further away from one another in matters of belief and practice. We won’t ‘prove’ anything to someone who speaks a language that is different than ours. We need more conversion in society, and less ‘winning’ argumentation.

Brilliant! I am late for a meeting but was so taken by your excellent insights and beautiful crafting of this argument that I couldn't stop reading. I have so much to respond to in what you say. But in brief: In my work with clients of all walks of life with mixed constituencies, the first thing we have to do is to develop a common language, where we all understand the 'terms of art' if only for the duration of our project or session. My team and I have learned that this cannot always be done so directly but to engage the participants in an exercise which allows each to demonstrate and share their worldview in a condensed form and time. Then in natural generosity, free and unimposed, people gravitate towards speaking the same language in order to be understood, much like the impulse as described in your prelude of Augustine.

I've often wondered how do we get that kind of commonality of terms in the public discourse but have yet to see anyone else be aware or address it as succinctly or as beautifully as you just have. Thank you kindly for sharing your wisdom!