Maybe a month ago, a priest friend told me that he no longer likes to use the word “faith” in his homilies, in his teaching, or even in his conversations with parishioners. He said that the word “faith” has lost its meaning because the word “faith” has assumed so many different meanings in our spiritual language. We talk about personal faith in God, or in someone else. We talk about faith as an act of believing what God tells us. We talk about faith as a supernatural virtue infused into our souls at the moment of our baptism. There are so many different uses for the word “faith,” and so my friend no longer thinks the word is very helpful.

I understand why my friend says what he says about the word “faith.” But I actually like the ability to use the word “faith” in so many different ways. At the conclusion of today’s Gospel, Christ asks the disciples, and so he also asks us: But when the Son of Man comes, will he find faith on earth? What kind of faith do you think it is of which Christ speaks? Maybe Christ means the definition of faith that we know from The Letter to the Hebrews: faith is the substance of what is hoped for, the evidence of things not seen. Maybe Christ speaks of faith as a theological virtue, or as an act of believing God, or as a foundational belief in God.

A thought that came to my mind is that the question that Christ asks us, because of our First Reading from the Book of Exodus, refers to a special kind of faith: a faith in our place in the Church. I marvel at the image we are given in our First Reading today. Amalek makes war on Israel, and Moses sends Joshua into battle to defend God’s chosen people. Moses climbs to the top of a hill to pray over the battle, and as long as his arms are raised high in the air, the army of Amalek suffers many casualties. But the battle continues for some time. Moses grows tired; he lowers his arms to rest but when he does so Israel’s army begins to lose the battle. So, Aaron and Hur spend the whole of a day supporting the arms of Moses, keeping them raised high in the air. Joshua wages war, Moses prays, and Aaron and Hur spend hours keeping the arms of a grown man raised high in the air.

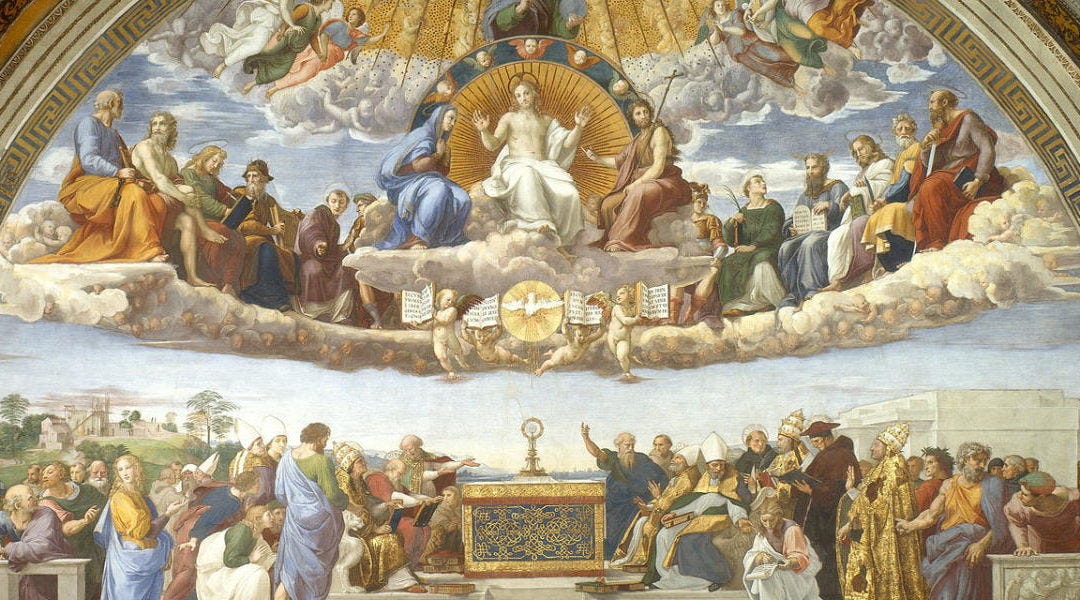

Each of the characters in today’s First Reading from the Book of Exodus is given a role to perform for the good of Israel. And so long as each character performs the role that is given to him, victory belongs to Israel. There is an image here of the Church, an image that St. Paul will develop centuries later in his First Letter to the Corinthians. An image of the Church as the body of Christ, a body composed of many members. A body whose health and vibrancy is assured so long as each individual part—every organ, every bit of tissue and sinew and bone—performs its function well. The good of the whole depends entirely upon the capacity of each member to perform his or her solemn obligation for the sake of the body.

Every Christian, by virtue of their baptism, is given a vocation, a mission, a role to perform for the sake of the Church . . . for the sake of Christ’s body. And the good of the whole depends entirely upon our ability to fulfill our solemn obligation, to perform the role that has been given to us. And like Aaron and Hur standing on the top of a hill overlooking a great battle, we are called to perform our function for the sake of the body untiringly, unwearyingly, and without pause or hesitation. And yet how often do we fail to fulfill our solemn obligation? Too often, is the answer; too often do we fail to fulfill our solemn obligation to perform the role that has been given to us. And why do we fail to meet our solemn obligation? Well, we allow ourselves to become distracted by the functioning of other parts of the body. We start to question, to criticize, and to call into doubt the work of some other organ or bit of tissue or sinew or bone. We lose sight of the role given to us for the good of the Church because we become consumed with concern for what the other members of Christ’s body are doing, or failing to do.

And the consequence is the ill-health of the Church which is the body of Christ. The body starts to consume itself; the body ceases to function; the body becomes cannibalized by worry and anxiety and doubt. We do not see any kind of criticism or questioning or calling into doubt in our First Reading today. There is no grumbling or complaining or condemning to be found in Moses or Joshua or Aaron or Hur. Maybe later in the evening, the battle won, Aaron and Hur complained bitterly about the failure of Moses to keep his own hands raised in the air or of his unwillingness to stand for the duration of the battle while so many below him were fighting and dying. Or maybe as he looked out upon the field of battle, Moses questioned the decisions made by Joshua regarding how to wage a war, doubting that Joshua possessed the competency to lead an army. Or maybe in the midst of this great battle, Joshua looked up on the hilltop and saw Moses there seated on a rock and criticized the old man for not joining the fight, for acting as a coward, for failing to lead the people of Israel into battle. Maybe the true story of what happened during the battle against the Amalekites contains exactly these kinds of grumblings and judgments and expressions of doubt and outrage. But no such complaining or criticism is handed down to us by way of revelation. It seems that Moses, Joshua, Aaron, and Hur each performed the role given to them and so a victory is claimed by Israel.

We are called to perform the role given to us for the good of the whole in just this way. And the fulfillment of our solemn obligation to live out our vocation and our mission is an act of faith—a faith free from doubt or hesitation or wavering commitment. A faith that never tires nor grows weary. Our lack of faith in the place given to us in the body of Christ which is the Church causes our eyes to wander. We get distracted. We start to fixate on the failures of others to perform their role, to function as they should, or to act as we would act if we had been given their mission or vocation. And so the body of Christ consumes itself; it grows unhealthy; its organs cease to function, its bones grow feeble, and the tissues that hold the Church together weaken. The body dies because its parts no longer do their work.

The question that Christ asks us at the conclusion of today’s Gospel is a question about our faith in the life that has been given to us in the Church. Each of us has a vocation—a mission—that we must perform for the good of the whole. We are members of Christ’s body. And we can allow nothing to distract us from our solemn obligation. To do less is to let the body of Christ weaken and grow ill.

Homily preached on October 15th at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

First we must discern what our mission is.