The following was given at The Basilica of the Assumption on February 21, 2024 during the Lenten Pilgrimage of the Seek the City to Come planning process.

Introduction

I’ve been asked to give this small catechesis tonight on the Eucharist with a focus on worship. I think fundamentally there are two sides to worship, which are in short, what we worship and how we do it. I remember a quip one of my seminary friends made while he was working on an advanced degree in liturgy. He said, “As a liturgist, I don’t need to know why you’re a heretic; what I care about is how we’re supposed to burn you at the stake.” Worship, in the fullest sense, must involve both. Right worship—worshiping as the Church instructs us—is just as much about getting the who and the how correct. We can carry out, with exact precision, a ritual sacrifice to an idol (which is to say, a construct of God of our own making); or we can attempt to praise the true God in a way that defies his own directives. There are examples of both in the Bible: the worship of the golden calf at Sinai for one and the practice of temple prostitution among the Christians in Corinth for another. Now, for us in Baltimore in 2024, neither (one would hope!) are exactly our problems, but it is not all that difficult to draw analogies between them and our own experience and struggles with idolatry and contrived forms of worship. We worship other gods whenever we give something other than God the time and priority that God alone deserves; and we worship the true God wrongly when we worship on our own terms, when liturgy is fabricated and ceases to be mystery. My goal this evening is to offer a corrective on both counts, so that we know better who we worship and how we should worship him.

One of the most dramatic scenes in the New Testament, I think, is Paul’s speech in the book of Acts at the Areopagus in Athens, which was a sort of public forum where trials would be held. It’s not exactly clear whether Paul was on trial himself or just simply used the opportunity to make an extemporaneous proclamation of the Gospel. In any case, Paul’s words are powerful. While walking around Athens, he noticed an altar “to an unknown God” and cites familiar local poets who spoke of this deity as the one “in [whom] we live and move and have our being.” Now in this great court, Paul declares, “What therefore you worship as unknown, this I proclaim to you” and announces to them the real, living God who they have hitherto sought and worshipped in shadows. One of the lessons here for us is that without God’s initiative, without him as it were stepping out from behind the curtain, we would not know God and we would not know how to worship him. Our altars would still be inscribed “to an unknown God” and our sacrifice would be fruitless.

So, in thinking about the Eucharist as worship revelation is our point of departure. For our worship to be authentic and effective, God must first show us his face and teach us how we are to worship him. Now, we don’t need to wait around for God to do this—he has already done it! We have all we need to worship rightly. What we need to do is to make sure that we are receptive to the revelation God has graciously given us and adapt ourselves to it. My reflections tonight are, therefore, separated between the two halves of what revelation tells us about worship: who we worship and how we worship.

Who We Worship

For a couple of years my home parish had a priest help out on weekends who did something when he said Mass that caught my attention and peaked my curiosity—but which I will nevertheless admit in the second part of this talk is something one should not do. As he said the Eucharistic Prayer, Father Visitor would substitute the specific names of the Trinity where there are pronouns or words like “Lord” that could mean either Father, Son, or Holy Spirit. This helped my young mind expand from simply praying to “God” to praying “To the Father, through the Son, in the Holy Spirit,” which is the basic form of Christian prayer. In the Mass, the Eucharistic Prayer has exactly that Trinitarian structure, and this is essential to understanding what exactly we are doing when we offer the Mass. Mass is offered in a Trinitarian manner. As we will see, the Mass is the sacrifice of the Son offered to the Father in the unity of the Holy Spirit. For this reason, the God we worship is not “unknown” nor a God of our own ideation. This God, a Trinity of persons, is only known by faith—faith in the revelation the Triune God has made of himself in salvation history. That is to say, the who of worship is objective. We are always praying to a God who has revealed himself to us, and who he has revealed himself to be must shape the form of our prayer.

Some of the prayers of the Mass change day to day, but the central prayer of every Mass is called the Eucharistic Prayer. The Eucharistic Prayer, also, can change day to day, but each Eucharistic Prayer retains the same basic elements. For reference, I’m going to use the first Eucharistic Prayer, which is ‘the long one with all the saints.’ Eucharistic Prayer I is also called The Roman Canon because it has been used in the Roman Rite since the 7th century and was from then the only Eucharistic Prayer in the Roman Rite until 1969. That is to say, Eucharistic Prayer I has pride of place within the liturgy and is best suited to teach us about what the Church has always believed.

The Canon begins, “To you, therefore, most merciful Father, we make humble prayer and petition through Jesus Christ, your Son, our Lord, that you accept and bless these gifts, these offerings, these holy and unblemished sacrifices.” The Eucharistic Prayer is offered to the Father since the Eucharist is the sacrifice of Christ made really present in a sacramental mode. This means that when the Eucharist is celebrated, the saving mystery of the Cross is celebrated anew. This does not mean, as some of our Protestant brothers and sisters would accuse us, that when we celebrate Mass Jesus is crucified again. If that were the case, we should never say Mass! Instead, according to Vatican II, “our Savior instituted the Eucharistic sacrifice of His Body and Blood. He did this in order to perpetuate the sacrifice of the Cross throughout the centuries until He should come again, and so to entrust to His beloved spouse, the Church, a memorial of His death and resurrection” (SC, 47).

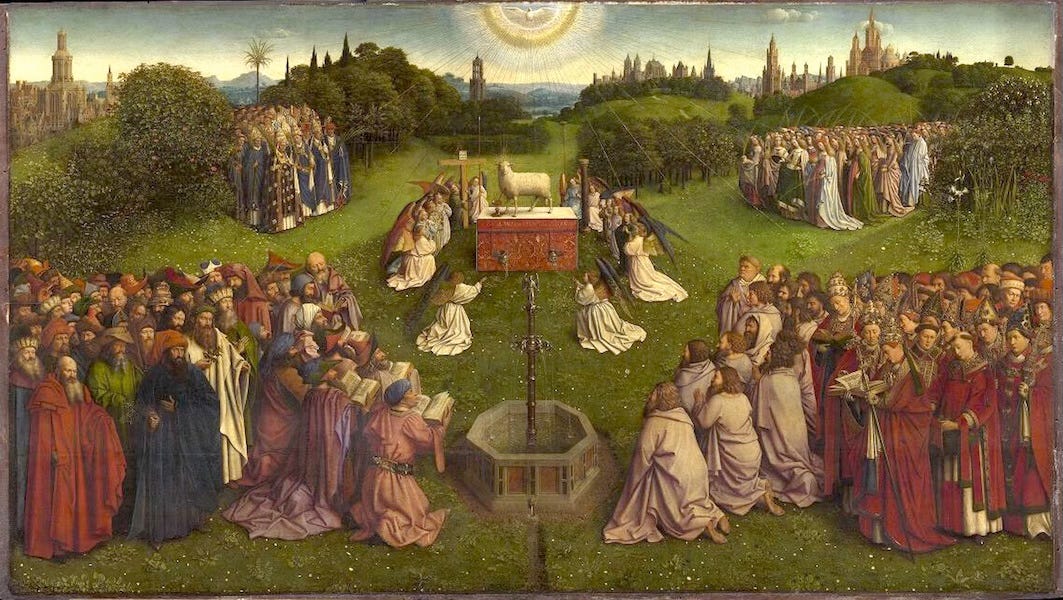

Now, and for this reason, the Eucharist is offered by Christ to the Father, since the Eucharist is the sacramental continuation of the sacrifice rendered by Christ to the Father on the Cross. Thus, the Canon begins: “To you… most merciful Father… through Jesus Christ…” This has some very significant implications: (1) Because the Mass is the sacrifice of the Cross, the Mass is equally as powerful as the sacrifice of the Cross. They are the same ‘thing’, so they have the same ‘effect’. (2) Because this is true of each and every Mass, then each and every Mass contains the full power of the Cross, which is to say every Mass is infinitely efficacious and beneficial. (3) Because the Mass is the Cross, then whenever, wherever, however, and by whoever the Mass is celebrated, the same Mass—the same Eucharist—is celebrated in every time and place. This is why the Eucharist is both the sacrament of unity and charity, gifts for which many of the prayers of the Mass ask. So, whenever we celebrate Mass, we celebrate not only as this particular group of people in this particular place, but as the full Body of Christ, spread throughout the entire world, in communion with all the saints and in one voice with all the angels.

The fourth implication of the Mass being the sacrifice of Christ is worth spending a moment longer on. If the Mass is really Christ’s work, then where is he? Vatican II teaches there are four ways in which Christ is present in the celebration of the Eucharist: (a) in the person of the minister—i.e., the bishop or priest; (b) in the Eucharist itself, as the full humanity and divinity of Christ; (c) in the words of holy Scripture read during Mass; and (d) in the Church itself: “Christ indeed always associates the Church with Himself in this great work wherein God is perfectly glorified and [people] are sanctified. The Church is His beloved Bride who calls to her Lord, and through Him offers worship to the Eternal Father” (SC, 7). So, Christ is present in the minister, the Eucharist, the Word, and the Church. I want to make a couple of points about the first and the last.

Christ is present in the minister (bishop or priest) as the one who acts in the person of Christ. This is an important and necessary distinction. Having received the sacrament of Holy Orders, the minister guarantees that the celebration that takes place really is the mystery it purports to be. Obviously, people can gather together and pray at any time and in any fashion they desire, and they do not need an ordained minister to be present for it. But to celebrate Mass, and the other sacraments, the Church’s minister must be there because they have the specific grace of acting in the person of Christ. Here is the difference. When I go to the chapel to pray, like anyone else, I ask God for certain things—and it’s really up to him whether or not I receive them. As a priest, I don’t have any more clout than anyone else, and, I assure you, my prayers go just as unanswered as yours. However, when I go to the chapel, put on vestments, pull out the chalice and paten, and say Mass, I am guaranteed that the specific words I pray, “This is my Body” and “This is my Blood” really make the Lord’s Body and Blood present because I pray them, not as a member of the Church, but in the person of Christ. Now, I don’t say all this to stand above you. On the contrary, I rely just as much upon this mystery as you do! When I receive the Eucharist that I have just ‘made’ in my hands, I want to be just as sure that it’s the Body of Christ as you. When I go to confession, I want to be just as sure I’ve received mercy as you when you come to confession to me.

Now for all this talk on the importance of the minister, we cannot forget the importance of the people. As Cardinal Newman once remarked (well before Vatican II) “Who are the laity? … the Church would look foolish without them.” The primary concern of Vatican II with regard to the liturgy is that the faithful should be really, fully, and consciously engaged in the mystery of the Lord’s Cross they are celebrating. This does not mean, as it is often taken to mean, that everyone must be given a job to do during Mass. No, everyone’s job during Mass is to pray. The priest is to pray, the people are to pray, and their prayer is different, but both are doing the same thing. Christ is present praying in the priest. Christ is present praying in the people. Christ, who (last I checked) only has one Body is present in both, rendering the perfect sacrifice to the Father in the unity of the Holy Spirit. I will say more on what the people’s prayer looks like in the next half.

The final thing to say about who we worship is that discovering the who is a lifelong endeavor. There is an ancient adage and important theological principle: lex orandi, lex credendi. The law of prayer is the law of belief. This expression is a two-way street. We learn how to pray from what we believe, and we learn what we believe from how we pray. The more we learn about the Trinity, the more we will be drawn into the sacrifice that the Son offers to the Father in the Holy Spirit. And if when we worship we truly lift up our hearts, then we will be drawn to know more deeply the God who has revealed himself to us and given us the grace of worshipping him and entering into communion with him.

How We Worship

How we worship follows from who we worship. If the who is the God who reveals himself to us and not a God we create of and for ourselves, then neither can our worship be the product of our own creation. Both God and the right way of worshiping God are objective—i.e., not subjective, human constructs that we can manipulate at will. Now, there must necessarily be a subjective dimension to worship—that is to say, we cannot simply perform the objective rituals as they are prescribed without entering into the great mystery that they signify. And this incorporation of the liturgy into our lives will be as individual and personal as we are individual persons. But all the same, the liturgy never loses the objective dimension even as it becomes ‘ours’. What I’m trying to sketch in the second half of this talk is finding the right point of intersection between the objective and subjective dimensions of the liturgy, and this point of intersection is what we mean by right worship.

On the objective side, both the minister and the people must be faithful to the officially promulgated rites of the Holy Roman Church. I will speak first to the minister’s and then to the people’s fidelity.

The minister is bound to say Mass as stated in The Roman Missal, with the same being equally true for the other sacraments and their respective books. The reason here, following up what we said a moment ago, is that the liturgy is the work of Jesus Christ and not a work of private or personal devotion. When we pray privately, we should use our own words which flow from the heart; but when we pray ecclesially—i.e., as the Church—we should use the words the Church gives us, for the Church is founded by Christ and entrusted with the sacred mission of continuing his presence on earth, principally through the celebration of the sacraments. Now, within the celebration of the sacraments, it is true that not every word carries equal importance. We call the ‘sacramental formula’ the specific words that must be said for the sacrament to be celebrated validly. In the Mass, these are the words of consecration said over the bread and the wine. Without them, the consecration does not take place. While it is technically true that changing, adding, or omitting other words of the Mass does not affect the validity of the Mass, this does not give the minister any justification to do with them as he wishes. I agree very much with Pope Benedict XVI who often said that the minister’s manipulation of the liturgy according to his own desires is among the very worst forms of clericalism. In doing so the minister says that he knows better than the Church, which is grave sin of pride. It must be said that the official liturgical books do at certain points allow for an amount of creativity. Sometimes the Missal will say, “in these or similar words.” Certainly, in those cases the minister is perfectly within his rights to make adaptations; but even then, he should only do so when the circumstances would seem to require it. Within the Mass, by the way, there are hardly any such directives (“in these or similar words”). They are far more common in the celebration of the sacraments and usually are found in words of introduction, where the situation might require a bit of a different tone than what the official text suggests. But within Mass, the priest is more limited by the rubrics to giving occasional commentary on what’s going on, if and to the extent he sees fit. In the immediate implementation of the new Missal following the Council, this made a good amount of sense, as everything about the liturgy was remarkably new. Now, these explanations are usually perceived as redundant by those who already know what is going on. And I find the best way to teach those unfamiliar with the Mass about it is simply to let them experience it in all its beauty and mystery, and outside of Mass offer opportunities to explain it and answer people’s questions.

So, returning to the story I shared earlier about the priest who would help out at my childhood parish, he was not in the right for changing the words of the Eucharistic Prayer, even if his intention in doing so was perfectly good and legitimate. The words of the Mass are the words of the Mass, and the Mass doesn’t allow all that much flexibility. Now, to anticipate some objections I’m sure I’ve provoked, you might say this strips the liturgy of any individuality—and my response is yes and now. The liturgy is not supposed to be ‘mine’ or ‘ours’ (in the limited sense of a particular parish, diocese, or even culture). The Mass is catholic, which means everything. But it’s precisely by leaning into the objectivity of the liturgy that we allow the space that is necessary for each individual to find a place within it. If I can walk into any Catholic church around the world and no matter the language, the music, the art, the architecture, and still know that it is the Mass and, thus, the celebration of the Paschal Mystery of Jesus Christ, then I know where I fit into it. That is the beauty of the objective dimension of the liturgy—that the liturgy is never so isolated and insular that it becomes closed-off and exclusive to anyone else.

If you have ever looked inside The Roman Missal, you would see that the words the minister is to say are in black and the directions for what he is supposed to do are in red. Incidentally, this is where we get the word ‘rubric’ from the Latin word for ‘red’ — i.e., the liturgical instructions printed in red. In any case, you sometimes hear the expression thrown around that the priest should “Do the red, say the black.” The priest who taught me liturgy in seminary had a famous expression, which one class had put on a mug for him, that went, “Do the red, say the black is insufficient.” What’s missing between in what’s printed in the Missal is what we call the ars celebrandi, or the ‘art of celebrating’. This is where the liturgy becomes more beautiful. It extends to details great and small: from the quality of the priest’s vestments (they do not need to be expensive, but they should look dignified!), to the pace at which he walks, to whether or not he looks bored, to the intentionality with which he says the words, to the extent that he lets you see that he really believes them, to the thoughtfulness of his homily, to the prudential judgement about whether or not immediately after Communion is the really the best time tell people to sell 50/50 tickets. All of this goes into making the liturgy beautiful and allows for legitimate diversity within the boundaries given to us by the Church.

Very recently, there was a document issued by the Vatican Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith on the importance of the words that are necessary for the validity of the sacraments. In the accompanying introduction, Cardinal Víctor Manuel Fernández wrote, “We ministers are therefore required to have the strength to overcome the temptation to feel that we own the Church. We must, on the contrary, become very receptive to a gift that precedes us: not only the gift of life or grace, but also the treasures of the Sacraments entrusted to us by Mother Church. They are not ours! And the faithful have the right, in turn, to receive them as the Church disposes: it is in this way that their celebration corresponds to Jesus’ intention and makes the Easter event relevant and effective.”1 I encourage my brother priests here this evening to consider the way in which we celebrate the sacraments and ask whether we are truly being faithful to what the Church has given us; and I encourage the faithful here present to ask your priests, charitably, to celebrate the Mass and the other sacraments if they are not in the way that the Church intends. You have a right for the liturgy to be celebrated as it is supposed to be celebrated.

Turning now to the faithful, while Father is carefully and prayerfully praying the prayers provided to him in the Missal, what are the people to do? This is an interesting question that I’m not sure has a definite answer. In general, we are all (priest and people) supposed to enter into the Paschal Mystery of Jesus Christ—but how we go about doing that isn’t so clear. One image that I have always found helpful is to think of Mary and John at the foot of the Cross. Both participate in the same mystery, but each in their own way: one as Christ’s Mother and the other as his dearest friend. Each person worshiping at Mass participates in the same mystery but nevertheless worships as a distinct individual, a person unlike any other with whom God desires communion. So, what ‘works’ for one of us at Mass won’t necessarily work for another; however, there are some basic guardrails we should all stay within. In the interest of not generalizing one’s individual experience, I will stick to what is objectively general.

First and foremost, remember that being ‘active participants’ in the liturgy does not require you to at all times be actively doing something. We should think of active participation in the way that we participate when we attend a symphony. No one leaves the concert hall after hearing, for example, Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony complaining they couldn’t be a part of it because they couldn’t play an instrument or sing along with the musicians. One can attend the symphony and leave just as moved and changed from the experience as much as the musicians who perform on stage. The Mass is similar: there are those who have responsibilities to carry out in the sanctuary, and there are those who participate no less by praying in the pews. Both are equally required to pray and enter the mystery. In fact, the one with more to do is more likely to be distracted than the one who simply needs to show up and allow themselves to be changed by what they encounter.

Second, prepare for Mass by praying with the readings, starting with the Gospel. The Gospel is the most important of the readings, and the First Reading is paired to go with that Sunday’s Gospel. If you go in with the Gospel in mind, then when the Liturgy of the Word begins, you’ll already have an idea of where it’s going. Print subscriptions like Magnificat or The Word Among Us or digital apps like iBreviary are both helpful aids in preparing for Mass.

Third, try to learn about the Mass. Be curious about what the prayers mean, what the gestures signify, what the ceremonial is all about. You don’t have to be an expert in any of it, but nothing that happens during the Mass is meaningless. Everything visible is meant to draw us into the invisible mystery we celebrate together. Returning to the image of the symphony, in order to appreciate Beethoven’s Ninth, you don’t need to know anything about music theory or how to play an instrument, which not everyone is able to do. But knowing a bit about who Beethoven was as a person, where he was in his life when he composed the piece, and what was going on in the world at the time is all accessible information that will help us gain a better grasp of the music. The same is true with the Mass. You don’t need to be a liturgist and know all the history and development of every last detail. Start with the basics and work out from there. Bishop Barron’s series on The Mass is a good place to begin.

Finally, the adage lex orandi, lex credendi—the law of prayer is the law of belief—has a third term: lex vivendi. The law we pray and belief is the law by which we are to live. The liturgy—our worship of the Eucharist—must animate the whole of our Christian lives, as the Eucharist must ever be the source and summit of all that we do. The less we see Mass as an isolated event that takes place for one hour on Sunday mornings and more the prayer given to us by God that gives shape to all that we are and do the better.

Conclusion

By way of conclusion, as we move toward the reality of what the Church in Baltimore will be on the other side of Seek the City, we can all take comfort in the fact that though the where of our worship may change, the who and the how of our worship will always and everywhere remain the same. What we will be asked to let go of in the future—buildings and communities—are undoubtedly important; but what is most important—God and how he wants us to worship him—are always with us no matter what else in our life changes.

I give my last words this evening over to Pope Francis: “Here lies the powerful beauty of the liturgy… Christian faith is an encounter with [the Risen One] alive, or it does not exist. The liturgy guarantees for us the possibility of such an encounter. For us a vague memory of the Last Supper would do no good. We need to be present at that Supper, to be able to hear his voice, to eat his Body and to drink his Blood. We need Him. In the Eucharist and in all the sacraments we are guaranteed the possibility of encountering the Lord Jesus and of having the power of his Paschal Mystery reach us. The salvific power of the sacrifice of Jesus, his every word, his every gesture, glance, and feeling reaches us through the celebration of the sacraments.”2

Thank you for your time and attention. May God bless you.

Víctor Manuel Fernández, “Presentation” of the Note of the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith Gesits Verbisque (February 2, 2024).

Pope Francis, Desiderio Desideravi (June 29, 2022), 10-11.